Two decades after the attack on September 11th, filmmakers are grappling with the ugliness in how the CIA tried to get more information about future terrorist attacks, and the school of torture that followed. Scott Z. Burns’ “The Report” told of how whistleblowers started to realize the scope of torture in the War on Terror, and how much it did not work; Paul Schrader’s recent “The Card Counter” based its brooding nature on the psychological effects post-9/11 torture would have on the soldiers who enacted it. But as these filmmakers have sought a type of accountability, the stories of the tortured have received less visibility.

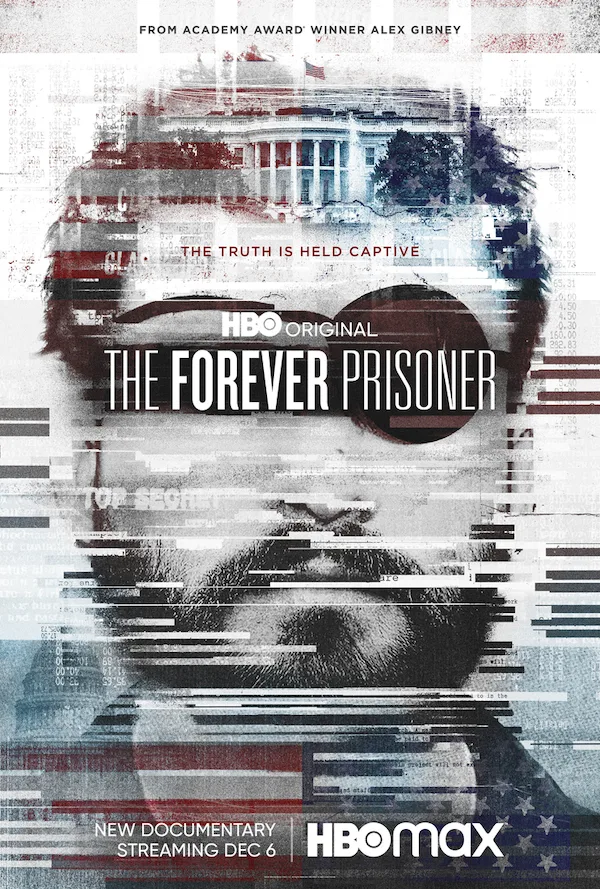

Enter Alex Gibney’s vigilant and infuriating “The Forever Prisoner,” which interviews real-life figures seen in those narratives—Daniel Jones, the FBI agent portrayed by Adam Driver in “The Report,” and someone who wore a black mask and did government-sanctioned torturing, as in “The Card Counter.” Gibney’s film proves to be a vital text in understanding the on-the-ground terror from the post-9/11 hunt for information and revenge, and the American barbarism that defines it. It centers the prisoner, Abu Zubaydah, as much as it can, even though he cannot be interviewed from his current cell on Guantanamo Bay; his presence is rather felt in the graphic hand drawings and brief entries about his experience. And in providing empathy to his torture as a human being, it also shows how America leaned on inefficient aggression and terror with methods that were proven not to be effective in acquiring information, while following half-baked leadership from key figures in the CIA. Gibney’s harrowing documentary provides that intimate scale, and allows us to then understand how this approach expanded until it hit the media spotlight with the photos from the Abu Ghraib prison in 2004.

Zubaydah is considered the first high-value detainee subjected to the CIA’s Enhanced Interrogation Techniques (known as EITs) but he still has not been charged with anything. The FBI agents who interrogated him before torture was involved (like Ali Soufan, who later left the agency) provide a grounded idea of who he was, and was not—he was not the number three target of Al-Qaeda in the hunt for Osama Bin Laden, as the public narrative went. Rather he was more of a middle man, who could connect people of far more heinous involvement. He was also a great source of information, this documentary argues, in that he helped identify Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the “principal architect” of the attacks on September 11th. But as this documentary effectively then explains with testimony and a clear timeline, the government then leaned on unproductive, extreme methods that produced less information from Zubaydah. “The Forever Prisoner” recounts the lengths to which he was tortured, and with its incredible access to previously redacted CIA accounts, the subsequent failure in getting much more information using those methods.

The efficient storytelling of Gibney’s documentary helps demystify the enhanced interrogation techniques—later agreed to be torture—and the process behind it. It was always surprising to me how much calculation there was to each act of torture, how much discussion there was in Washington about making what was happening in a black site in Thailand “legal,” or seem legal enough. It was meticulous; it was not done by random nobodies who would always be anonymous, but people like Dr. James Mitchell, who is one of Gibney’s interview subjects here, and helped write the book on how Americans could strategically destroy their captives psychologically. Mitchell talks throughout about wanting to avoid another attack if he could help it, which more speaks to the “fear and fury” that defined post-9/11. But Mitchell also talks about later being annoyed at how the Red Hot Chili Peppers was played on repeat, completely missing how Zubaydah was subjected to the same music at max volume for hours on end.

The film has the prolific documentarian thriving on his razor-sharp focus, along with his passion for digging for information and sharing his findings (including how he sued the CIA in order to release more records about the torture). Here, Gibney creates an expansive narrative that involves multiple witnesses and some juxtaposing details, while keeping it claustrophobic for the viewer to understand the grave lack of humanity. It is a tale filled with cruelty and unimaginable suffering, all by people that President Obama later described as “patriots” from the White House podium after saying “We tortured some folks.” All the while, Zubaydah’s drawings of being tortured (sometimes with drawings of CIA officials being blacked out) and his words are displayed with the cryptic nature of a quiet, white room, the images of being waterboarded or crammed into a small coffin indicating the immense traumatic activity. The drawings prove to be even more effective than the reenactments.

This is Zubaydah’s story, but it is not about what he is currently doing. Rather it is about how he is a mirror of accountability that needs the exposure Gibney is providing. The extremes uncovered in this film become revealing of what we accept as necessary, in what we as a nation rationalize as justice even without procedure. It is eye-opening, and yet also like Gibney’s best work, affirming in the worst ways.

Premiering tonight on HBO and subsequently available on HBO Max.