Near the beginning of “The Disappearance of Garcia Lorca,” a teenage boy attends an opening night in Madrid, Spain, in 1934–a performance of a work by the poet and playwright Federico Garcia Lorca. Twenty years later he recalls, “That night I learned that poetry could be an act of violence.” Backstage, he is introduced to the poet, who asks, “How old are you?” “Fourteen,” he replies. “So am I,” says the poet, adding, “Remember me.” Not long after, Garcia Lorca is dead, another victim of the Spanish Civil War. He had thought perhaps he was too visible to be assassinated by the forces of the fascist rebel Franco, but he was wrong. And ever since there has been a veil of mystery over questions of how Garcia Lorca was killed, and by whom.

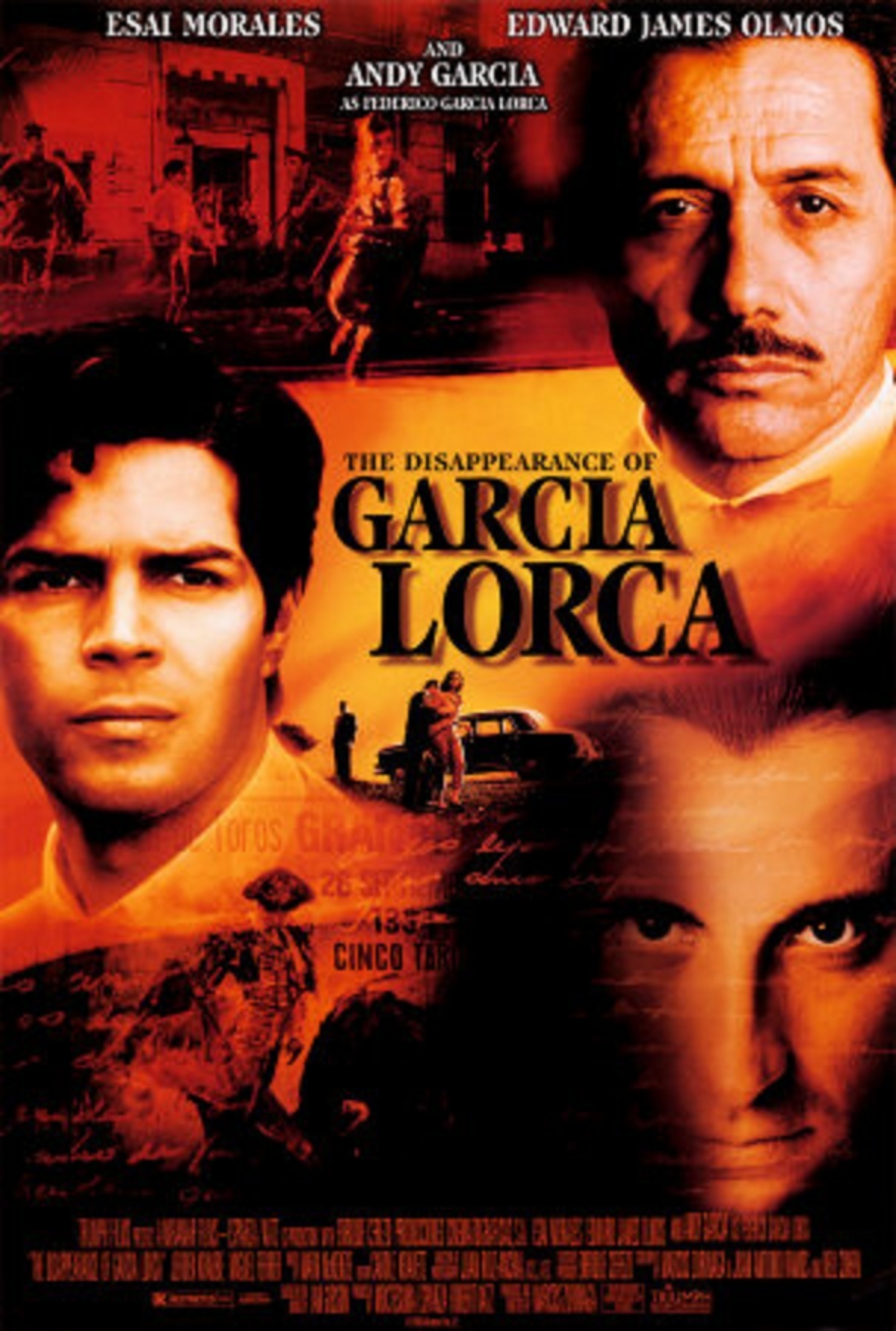

This movie, based on two books by Ian Gibson, is a reconstruction and speculation, told through the eyes of the boy, Ricardo, who moves with his family to Puerto Rico and tells his father one day in 1954 that he intends to return to Spain and try to find out what happened. For his father, all of that is in the past, and, with Franco still in power, best left there. But the boy, now grown to manhood and played by Esai Morales, returns anyway, and begins to unravel the secrets of the death.

Garcia Lorca, played by Andy Garcia, is seen in the movie as an artist whose very existence is a challenge to the insurgents. What is often forgotten about Spain, because it reverses the usual pattern, is that the elected government was left-wing, and the rebels were fascists; Franco was supported by Hitler and Mussolini, and the air battles in Spain were seen by historians as a dress rehearsal for the Luftwaffe.

To the rebels, the famous poet was a symbol, and his poetry like a red flag at a bullfight. But Garcia Lorca was also well-connected, with influence, with powerful friends. There is a scene where he strides confidently from a house to where some military men are beating his friend; he thinks his prestige will be enough to stop them, but he is wrong, and a fascist goon named Centeno (Miguel Ferrer) slugs him in the stomach. Garcia Lorca does not quite realize even after this event that his society has changed fundamentally, that a new class is taking power, that he is doomed.

Returning to Spain in 1954, Ricardo meets a publisher named Lozano (Edward James Olmos), who is bringing out a handsome edition of Garcia Lorca’s works. “But … didn’t you arrest him?” Ricardo asks. Lozano replies, “You’re a brave man, Ricardo. No one else has been brave enough to say that to me.” Lozano did sign the arrest order, and was possibly present at the death, along with others who would now rewrite their roles in history.

The lesson apparently is that the poets who are alive are a threat to repression, but dead poets can be safely embalmed as national treasures or legends. The film is also about how the secrets of the past still hold their power for revenge, if they are exposed, and in 1954 there are many people still alive who know how and why Garcia Lorca was killed–people whose current lives cannot accommodate that knowledge, so that Ricardo’s quest is a threat.

Ricardo enters a Madrid where there are suspicious eyes and ears everywhere, and a taxi driver (Giancarlo Giannini) may be a friend, or a spy. Where nothing is simple, and people who thought they had sufficient reason in 1934 to side with the fascists and the Third Reich no longer wish their association to be recalled. The movie is a murder investigation, really, except that Ricardo will also be discovering things about his own origin that he does not suspect.

Do people read Garcia Lorca today? Or poetry in general? Not many, I suppose. I read some of his poems after seeing the movie, and felt the passion. But Garcia Lorca is perhaps more important today as a symbol than as a poet, and this film is really not so much about him as about memory and history–about how poets are given most of their power not by those who love them, but by those who fear them.