There are three moments of perfect truth in “The Cure.” There are several passages that are very moving. And then there’s an impossible story that plays like a cross between a Disease of the Week movie and “The Goonies.” It’s possible that moviegoers in their earlier teens – the target audience – will like it a lot. I was derailed by the silly stuff, and by the movie’s conviction that it’s funny to play practical jokes about death.

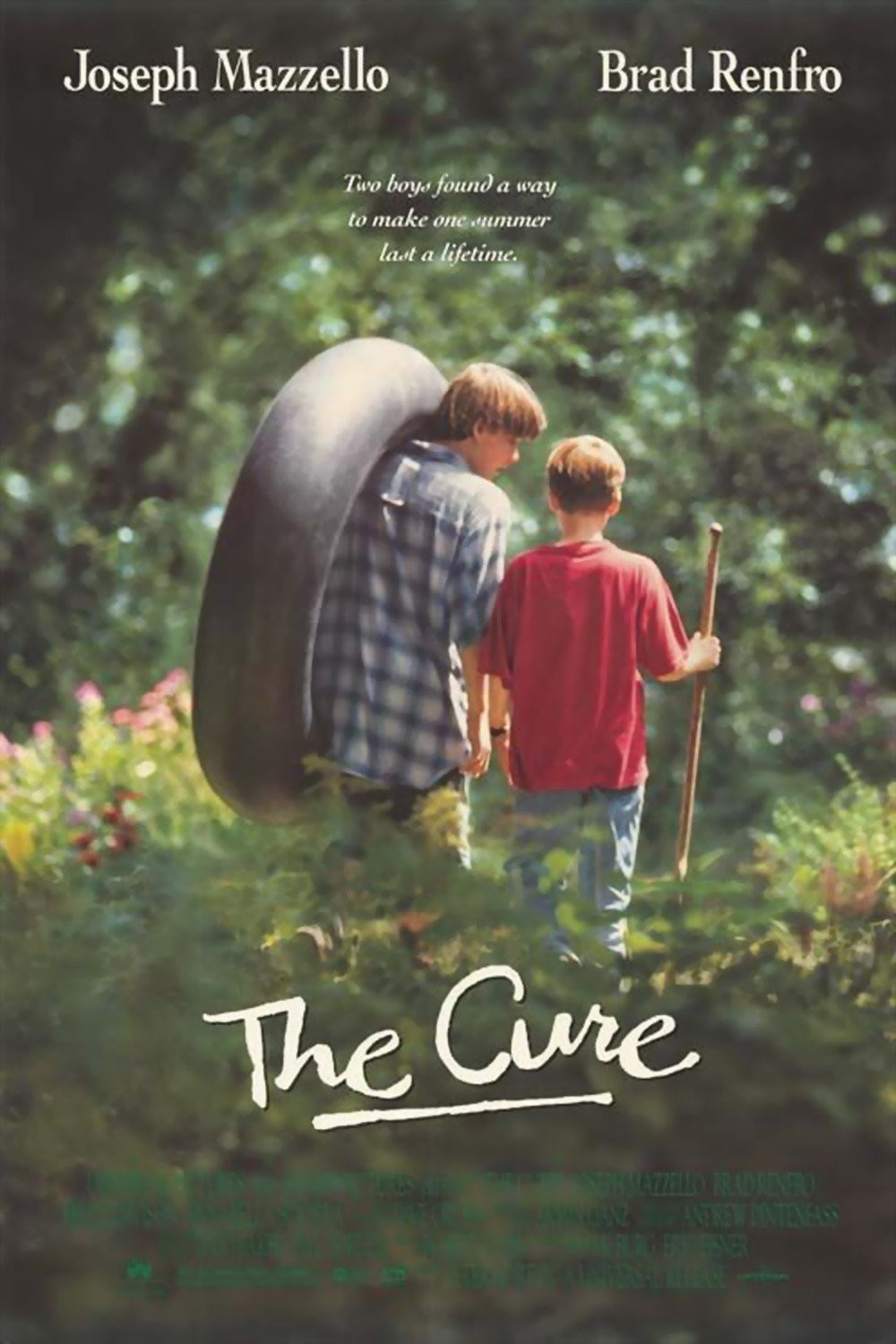

The movie takes place in a small Minnesota town where young Erik (Brad Renfro) has recently moved with his newly divorced mom (Diana Scarwid). Next door, behind a tall wooden fence, lives a boy named Dexter (Joseph Mazzello), who contracted AIDS through a blood transfusion. They’re about the same age, but Dexter, who is very small, explains cheerfully: “If you look at the lower limit of what’s considered normal for my age, I’m only 4 inches shorter.” Bullies at the school torment Erik as a “faggot” for being friends with Dexter, and Erik’s own mother advises him to keep his distance, which she defines as 7 feet. But the two boys become best friends, and Dexter’s mother (Annabella Sciorra) comes to love the rough-edged kid who has befriended her son. Strange, how real the Sciorra character seems, and how unconvincing Erik’s mom is (she spends the movie drinking, smoking and being mean-spirited).

Meanwhile, the boys are inspired by a movie they see on TV (“Medicine Man,” with Sean Connery finding a miracle cure in the jungle). Erik involves Dexter in harebrained home brew AIDS cures, including experiments with “The Periodic Table of the Candies.” (The theory here is that combinations of candies can cure AIDS; in practice, the scene plays like product placement for Butterfinger bars.) These scenes have a natural warmth, helped by convincing performances by Renfro, the non-pro actor discovered in “The Client,” and Mazzello, who never makes a play for sympathy. I liked their theoretical discussion of whether a lion or a shark would win in a fight.

But come on – are we really supposed to believe it when the kids read in a supermarket tabloid that a New Orleans doctor has discovered a cure for AIDS, and then they run away from home to float 1,200 miles down the Mississippi to find him? Wouldn’t there be a media storm and a manhunt? How far do you think two kids would get on a raft, towing an inflatable crocodile behind them? The plot then provides a couple of shifty pleasure-boat types who agree to carry them as passengers (see above objections), and, yes, the plot actually involves a chase into an Abandoned Warehouse, the desperate screenwriter’s friend. The speedboat trip is somewhat redeemed by a priceless exchange between young Dexter and a bimbo picked up along the way. (He: “You misspelled your tattoo. It doesn’t say `Angel.’ It says `Angle.’ ” She: “I’m aware of that now.”) The three perfect scenes are clustered toward the end. One comes after an unconvincing scene in which Dexter uses his disease to scare off a bad guy, and then is shaken to realize his blood is “poison.” Another comes when a doctor (Bruce Davison) explains why he believes in miracles. The third is a confrontation between the two mothers.

Those scenes have a greatness to them. But they fit uneasily into the same movie with stock villains, phony showdowns and the unlikely trip down the river. And then there’s that series of practical jokes that Erik and Dexter play in the hospital; they’re a miscalculation so enormous they destroy what should have been the most important scenes.