Near the start of “The Confirmation,” Anthony (Jaeden Lieberher), an eight-year-old boy who has returned to the church at the behest of his mother and stepfather, is in the confessional. The priest (Stephen Tobolowsky) asks the boy to recount his sins, but Anthony is at a loss. The priest goes through the usual list of possibilities: dishonoring his parents, lying to someone, wishing harm on someone, and having thoughts about sex. Anthony thinks about each one and concludes that, no, he hasn’t done any of those things (he isn’t even sure what would qualify as thoughts about sex). The priest gives him a penance of a few prayers to perform anyway, because surely the boy is either lying or doesn’t realize his own transgressions.

From the audience’s perspective, we don’t know if young Anthony is being dishonest or unaware of his sins, although, from a first glance, we might believe he’s telling the truth. He seems like a good kid.

We do know that, almost immediately after finishing his confession, he lies to his mother Bonnie (Maria Bello). She asks her son if he has completed his penance. He says he did, but we just saw him flee down the aisle of the church after barely beginning an Our Father. Something about the sight of the crucifix hanging above the altar spooked Anthony. Maybe it’s guilt about lying to the priest, or maybe it is the fear of eternal punishment for not having enough or the right kinds of sins to tell the priest.

It’s Anthony’s lie to his mother that matters, and by the end of writer/director Bob Nelson’s film (his first time directing), Anthony will have lied many more times to many people. He also will have stolen a couple of times, falsely accused someone of a crime, raised his fists to try to hurt a couple of people, and pointed a gun at someone. Even after all of that, he’s still a good kid.

This is a smart, effective coming-of-age tale about a boy figuring out that there are gray areas to life’s moral choices. The priest may say it’s a sin to lie and, hence, dishonor one’s parent, but what if that sin is committed in order to prevent a parent who’s a recovering alcoholic from taking a drink? Wouldn’t the greater sin be not lying? Is there a point at which a “sin,” in the black-and-white view of the priest, would cease to be a sin, because it’s done in the name of something good?

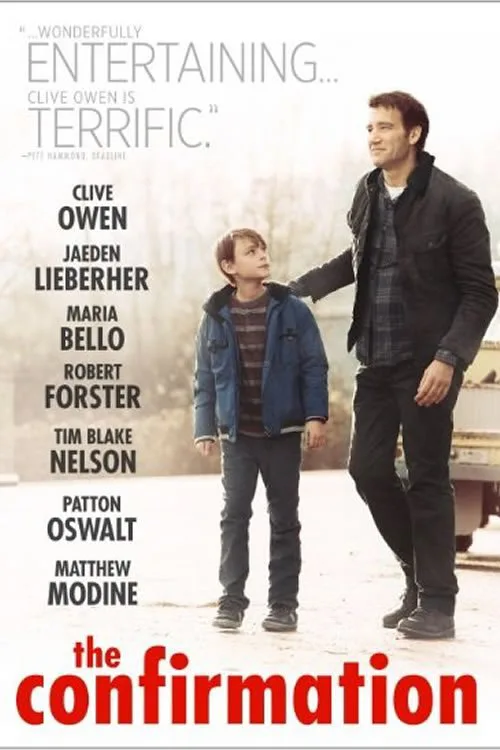

Reconciling that apparent contradiction is Anthony’s dilemma throughout the film, as he spends an eventful weekend with his father Walt (Clive Owen). Walt’s a down-on-his-luck carpenter who takes pride in his work, although the work has dried up for him as of late. He and Bonnie have divorced, and she has remarried (Matthew Modine plays the new husband). Walt’s a “freelancer,” which is just the way he has of saying that he’s unemployed. His pickup truck is on its last fumes, and he hasn’t been able to pay back the loan he took out on his house.

Walt stops at a bar to speak with some acquaintances about finding work. Anthony, worried about his dad returning to drinking, goes inside the tavern to retrieve Walt. Later, Walt receives a call offering him a job. That’s the good news. The bad news is that the specialty tools he needs for the work were stolen from his truck while Anthony was in the bar.

The rest of the film follows the father and son as they try to find the tools. They encounter a collection of oddballs and, if looking at it from a moral perspective, sinners. There’s Vaughn (Tim Blake Nelson), a reformed thief who “found Jesus” but still beats his young son Allen (Spencer Drever). That lead brings the pair to a comic interlude involving Drake (Patton Oswalt), another thief, whose claim to know everyone in town becomes doubtful. The only, clearly decent man of the bunch is Walt’s long-time friend Otto (Robert Forster), who comes at a moment’s notice to help Anthony with his father and to explain the effects of alcohol withdrawal to the boy.

Some of the situations in which Anthony finds himself aren’t particularly convincing. A handful of scenes involving the threat of (a pair of scenes with two different handguns) or actual violence (as Walt gets closer to finding his toolbox) feel over-the-top in the moment and are resolved with relative, unpersuasive ease. Most of the decisions for Anthony, though, are much more low-key—to take some change from Walt’s truck to buy a hamburger, to hide the car keys to prevent his father from taking a late-night trip to the liquor store, to lie on someone’s behalf to prevent any harm that might come to that person.

The story is grounded by the relationship between Anthony (Lieberher conveys the depth of a caring “old soul”) and Walt (Owen is also quite good as a man grappling with his pride), as well as their shared sense of doubt and worry. As Walt worries about his viability as a father, Anthony is concerned about his father’s health and wonders about the fate of his own soul, if he can’t even determine what is and isn’t a sin. There’s a blunt conversation about faith and conscience between the two characters in the early-morning hours.

The lesson is that religion can help to teach the way, even if Anthony doubts the particulars as his father does, but it’s up to the boy to know how to live as a good person. In its own way, “The Confirmation” is a parable about the difficulty of learning how to know.