Switzerland sure seems like a nice, socially-tolerant place. Early on in this film, which mixes archival photos and documentary interview footage with a dramatic reenactment of the events under consideration, one of the figures describes an event that was held to mark the 25th anniversary of the first publication of “The Circle,” a Swiss magazine catering to a gay male clientele. Marveling that guests came from all over the world, including America, to celebrate this milestone, he notes that parties thrown by “The Circle” were “ the only gay mega events in the world.” This particular occasion, as it happens, took place in 1957.

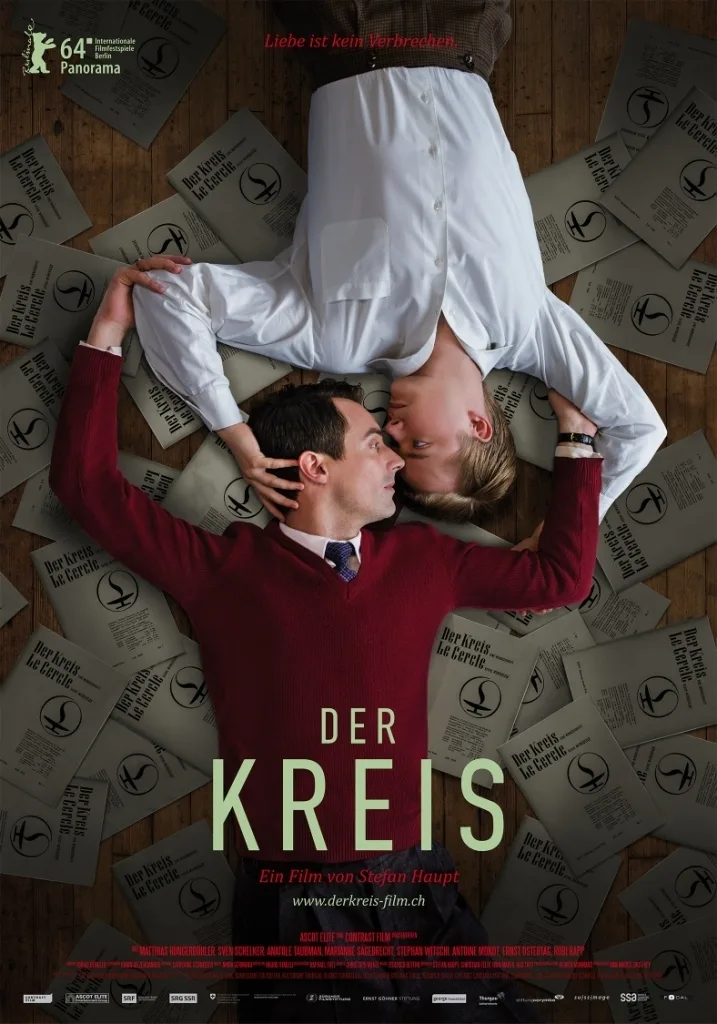

Which, if my math is correct, places the inaugural edition of “The Circle” in 1932. There’s really no equivalent in American publishing. But before you go getting ready to be too congratulatory to Switzerland—see, Harry Lime, it’s not just the cuckoo clock, but social justice!—director Stefan Haupt’s conscientious and engaging film makes clear right off the bat that, no, there was no place in Europe that was a gay utopia in this period and that even the most progressive-minded of societies had their growing pains. The movie economically limns the social currents spreading across post-war Europe by depicting one of its lead characters, Ernst (Matthias Hungerbühler) teaching Camus’ “The Stranger” to his French class, and being gently warned off such material by a colleague. “Wait until you’re certified” before risking such edgy material, the colleague suggests, and this advice feels like a leitmotif once we see how it pertains to the rest of Ernst’s life. He’s a gay man, and he makes exploratory journeys to the editorial offices of “The Circle” and its affiliated social events before getting into the life such as it is. It’s an underground existence, and Ernst and his kind don’t often encounter vicious rhetorical homophobia as a kind of puzzled tolerance and a general counsel of “hold on, if you behave yourselves you can ask to live your lives in the open a little later.” Complicating matters is the illegality of homosexuality in many corners of Europe, although that was not the case in Switzerland.

Haupt’s film moves along agreeably enough for a while, and the intercutting between the film’s real-life subjects, now at an advanced age, and their dramatized adventures almost 60 years ago, convincingly creates a rooting interest. But it’s only when the news breaks of the murder of composer Robert Obbussier, and the police’s suspicion of an inside-the-gay-community job, as it were (shades of the notorious “Cruising”), that the movie begins to build up some tension. Without getting showily indignant about it, “The Circle” demonstrates that the police conduct in the case gave individuals in the force the opportunity to vent their own homophobia—to use Obbussier’s and subsequent other killings as a way of pointing disapproval at the community that was enduring the damage. What this leads to, among its principal characters, is a realization that even the tolerance they’ve experienced isn’t sufficient: they have the inalienable right to live as they are in the full sight of society. “We are not criminals,” Ernst says near the end of the movie, and both the knowledge and the wherewithal to make the proclamation have been depicted as hard-won indeed.