Here’s what I remember: It was the second Friday in January and I was getting ready for school when “I Want to Hold Your Hand” came on the radio. The sound grabbed me instantly and I listened intently all the way through. At school that day, a lot of kids were talking about the song. Within a week or two, it was number one on the charts. Then, on February 9, the Beatles made their epochal first appearance on the “Ed Sullivan Show,” drawing 73 million viewers—the largest audience for an entertainment show in U.S. television history.

From unknowns to the Biggest Thing Ever in roughly a month: for sheer massiveness and suddenness, nothing has ever, and probably ever will, equal the Beatles’ conquest of the U.S. and, soon after, the world. The music’s infectious brilliance deserves most of the credit, of course. But it was also a unique historical moment. Edward Yang’s magisterial “A Brighter Summer Day,” set in Taiwan a few years before, makes the point that icons like John Wayne and Elvis had already created a global pop-culture idiom that especially united the young. But an unrepeatable set of social, technological and demographic circumstances in the early ‘60s forged the conditions for an unprecedented cultural explosion that spanned the worlds of music, fashion, television and film.

It’s hard to overstate the galvanic impact the Beatles had, almost instantaneously, on all those realms and more. And while the tunes were paramount, the image was just as revolutionary. When they stepped onto Sullivan’s stage, they might as well have been extraterrestrials. America had never seen anything like them. With their identical suits, astonishing “long” hair, anarchic humor and disarming good looks, they overturned every convention about musical acts were supposed to look and sound. It was the girls who screamed to high heaven, but we boys were just as ecstatic over their promise of a new era of creativity, freedom and cool.

It would be impossible to recreate the moment of the Beatles’ advent, but Ron Howard’s “The Beatles: Eight Days a Week – The Touring Years” does a great job chronicling that singular breakthrough. As its cumbersome title indicates, the documentary was founded on the wise choice of not trying to make a single feature that would encompass the band’s entire career. Rather, in focusing on the years when the band became the first ever to mount several world-spanning tours, it offers two things at once: a history of the Beatles during the years of their initial success; and a tribute to the group’s powers as a live act.

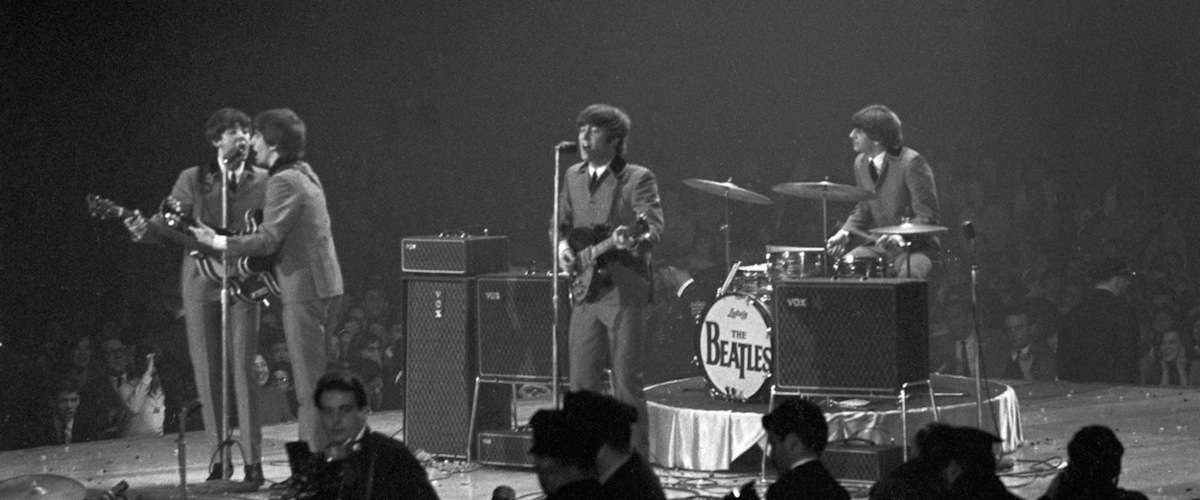

Regarding the latter, I would like to thank Howard for what to me is the best thing about the film: It gives us the entirety of many live songs and generous portions of others, rather then taking the all-too-common music-doc tack of showing the first few bars, then cutting to another scene or overdubbing the comments of some talking head. The first song we encounter, “She Loves You,” from a concert in Manchester, England, in 1963, is thrillingly confident and more powerful than such films were from that time, due to the great visual and aural enhancement that’s been provided courtesy of current technology—the mark of a loving restoration that distinguishes “Eight Days a Week” throughout.

The technology and concert situations of those days, of course, now looks almost hilariously primitive, as in the 1964 Washington, DC, show, just a few days after Ed Sullivan, where the musicians have to move their own amps and Ringo’s drum riser, yet serve up a brilliant rendition of “I Saw Her Standing There.”

As recently filmed interviews with Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr, and vintage ones with John Lennon and George Harrison, testify, the Beatles were as wonderstruck by their success as any of their fans. And Howard’s chronicle, which briefly sketches in the band’s early days and elides initial drummer Pete Best entirely, shows that after the group completed its conquest of Britain and Europe in 1963, the following three years of worldwide renown had a true dramatic arc.

1964 was Beatlemania; euphoria carried the four musicians from one success to another. They reported having a blast with director Richard Lester making “A Hard Day’s Night,” which added movie stardom to their repertoire; and five of their singles occupied the top five places on the U.S. charts at one time. In 1965, seeming to chafe against the confines that success had already brought them, they started smoking lots of pot, experimented and expanded their horizons musically with “Rubber Soul,” and didn’t have nearly as much fun filming “Help!,” the title song of which seemed to summarize Lennon’s reaction to their elevation.

But 1966 was the killer. They got run out of the Philippines for supposedly insulting the president’s family, and faced protests in Japan for playing the Budokan, which purists thought should be reserved for judo. And Lennon’s taken-out-of-context remarks about the Beatles being more popular than Jesus drew a firestorm of criticism in the U.S. Fittingly, given that the band had forced the integration of Florida’s Gator Bowl when it played there, some of the Bible Belt protests were led by Ku Klux Klan. After their August show in San Francisco, the band decided to give up touring. (The film goes on to note the recording triumphs of the following year, including “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.”)

Two points stand out in this chronicle. One, The Beatles were hugely industrious during this period (apart from a brief lull in early 1966). Besides their extensive touring schedule and making movies, they were writing and recording songs at an astonishing clip, and the quality of that music is still blazingly evident today. The second point is that they survived the maelstrom, and especially the crucible of 1966, by being as tight and mutually supportive as four best friends could be. Given the acrimony that came later, recalling this camaraderie today is revelatory and wonderfully heartening.

While it has commentary by interviewees ranging from Elvis Costello to Whoopi Goldberg (whose memories of Beatle fandom are warm and moving), the film’s heart involves the Beatles performances it gives us, which remain electrifying after all these years. The group’s fans today, of any age, are bound to welcome “Eight Days a Week,” in which Beatlemania’s mid-‘60s comet of joy and astonishment is thrillingly captured.

When the film is shown in theaters, it will be followed by a beautifully restored version of the band’s 1965 performance in the concert doc “The Beatles at Shea Stadium.”