We live in an age of brutal manners, when people crudely say exactly what they mean, comedy is based on insult, tributes are roasts, and loud public obscenity passes without notice. Martin Scorsese‘s film “The Age of Innocence,” which takes place in 1870, seems so alien it could be pure fantasy. A rigid social code governs how people talk, walk, meet, part, dine, earn their livings, fall in love, and marry. Not a word of the code is written down anywhere. But these people have been studying it since they were born.

The film is based on a novel by Edith Wharton, who died in the 1930s. The age of innocence, as she called it with fierce irony, was over long before she even wrote her book. Yet she understood that the people of her story had the same lusts as we barbaric moderns, and not acting on them made them all the stronger.

The novel and the movie take place in the elegant milieu of the oldest and richest families in New York City. Marriages are like treaties between nations, their purpose not merely to cement romance or produce children, but to provide for the orderly transmission of wealth between the generations. Anything that threatens this sedate process is hated. It is not thought proper for men and women to place their own selfish desires above the needs of their class. People do indeed “marry for love,” but the practice is frowned upon as vulgar and dangerous.

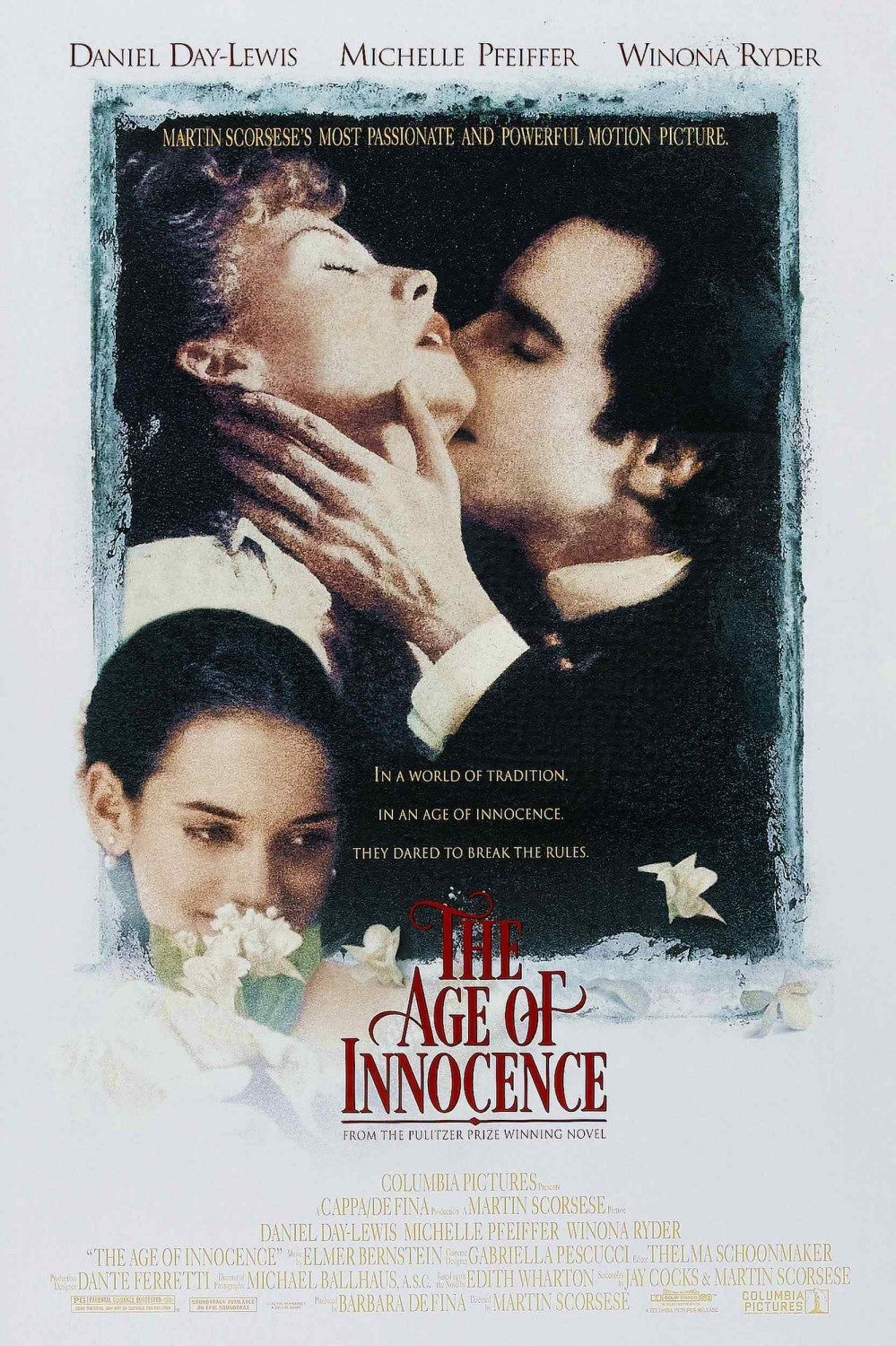

We meet a young man named Newland Archer (Daniel Day Lewis), who is engaged to marry the pretty young May Welland (Winona Ryder).

He has great affection for her, even though she seems pretty but dim, well-behaved rather than high-spirited. All agree this is a good marriage between good families, and Archer is satisfied – until one night at the opera he sees a cousin who has married and lived in Europe for years. She is Ellen, the Countess Olenska (Michelle Pfeiffer). She has, he is astonished to discover, ideas of her own.

She looks on his world with the amusement and detachment of an exile.

She is beautiful, yes, but that isn’t what attracts Archer. His entire being is excited by the presence of a woman who boldly thinks for herself.

The countess is not quite a respectable woman. First she made the mistake of marrying outside her circle, taking a rich Polish count and living in Europe. Then she made a greater transgression, separating from her husband and returning to New York, where she stands out at social gatherings as an extra woman of undoubted fascination, who no one knows quite what to do with. It is clear to everyone that her presence is a threat to the orderly progress of his marriage with May.

This kind of story has been filmed, very well, by the Merchant-Ivory team. Their “Howards End,” “A Room with a View” and “The Bostonians” know this world. It would seem to be material of no interest to Martin Scorsese, a director of great guilts and energies, whose very titles are a rebuke to the age of innocence: “Mean Streets,” “Taxi Driver,” “Raging Bull,” “GoodFellas.” Yet when his friend and co-writer Jay Cocks handed Scorsese the Wharton novel, he could not put it down, and now he has filmed it, and through some miracle it is all Wharton, and all Scorsese.

The story told here is brutal and bloody, the story of a man’s passion crushed, his heart defeated. Yet it is also much more, and the last scene of the film, which pulls everything together, is almost unbearably poignant because it reveals that the man was not the only one with feelings – that others sacrificed for him, that his deepest tragedy was not what he lost, but what he never realized he had.

“The Age of Innocence” is filmed with elegance. These rich aristocrats move in their gilded circles from opera to dinner to drawing room, with a costume for every role and every time of day.

Scorsese observes the smallest of social moments, the incline of a head, the angle of a glance, the subtle inflection of a word or phrase. And gradually we understand what is happening: Archer is considering breaking his engagement to May, in order to run away with the Countess, and everyone is concerned to prevent him – while at no time does anyone reveal by the slightest sign that they know what they are doing.

I have seen love scenes in which naked bodies thrash in sweaty passion, but I have rarely seen them more passionate than in this movie, where everyone is wrapped in layers of Victorian repression. The big erotic moments take place in public among fully clothed people speaking in perfectly modulated phrases, and they are so filled with libido and terror that the characters scarcely survive them.

Scorsese, that artist of headlong temperament, here exhibits enormous patience. We are provided with the voice of a narrator (Joanne Woodward), who understands all that is happening, guides us, and supplies the private thoughts of some of the characters. We learn the rules of the society. We meet an elderly woman named Mrs. Mingott (Miriam Margolyes), who has vast sums of money and functions for her society as sort of an appeals court of what can be permitted, and what cannot be.

And we see the infinite care and attention with which May Welland defends her relationship with Newland Archer. May knows or suspects everything that is happening between Newland and the Countess, but she chooses to acknowledge only certain information, and works with the greatest cleverness to preserve her marriage while never quite seeming to notice anything wrong.

Each performance is modulated to preserve the delicate balance of the romantic war. Daniel Day Lewis stands at the center, deluded for a time that he has free will. Michelle Pfeiffer, as the countess, is a woman who sees through society without quite rejecting it, and takes an almost sensuous pleasure in seducing Archer with the power of her mind. At first it seems that little May is an unwitting bystander and victim, but Winona Ryder gradually reveals the depth of her character’s intelligence, and in the last scene, as I said, all is revealed and much is finally understood.

Scorsese is known for his restless camera; he rarely allows a static shot. But here you will have the impression of grace and stateliness in his visual style, and only on a second viewing will you realize the subtlety with which his camera does, indeed, incessantly move, insinuating itself into conversations like a curious uninvited guest. At the beginning of “The Age of Innocence,” as I suggested, it seems to represent a world completely alien to us.

By the end, we realize these people have all the same emotions, passions, fears and desires that we do. It is simply that they value them more highly, and are less careless with them, and do not in the cause of self-indulgence choose a moment’s pleasure over a lifetime’s exquisite and romantic regret.