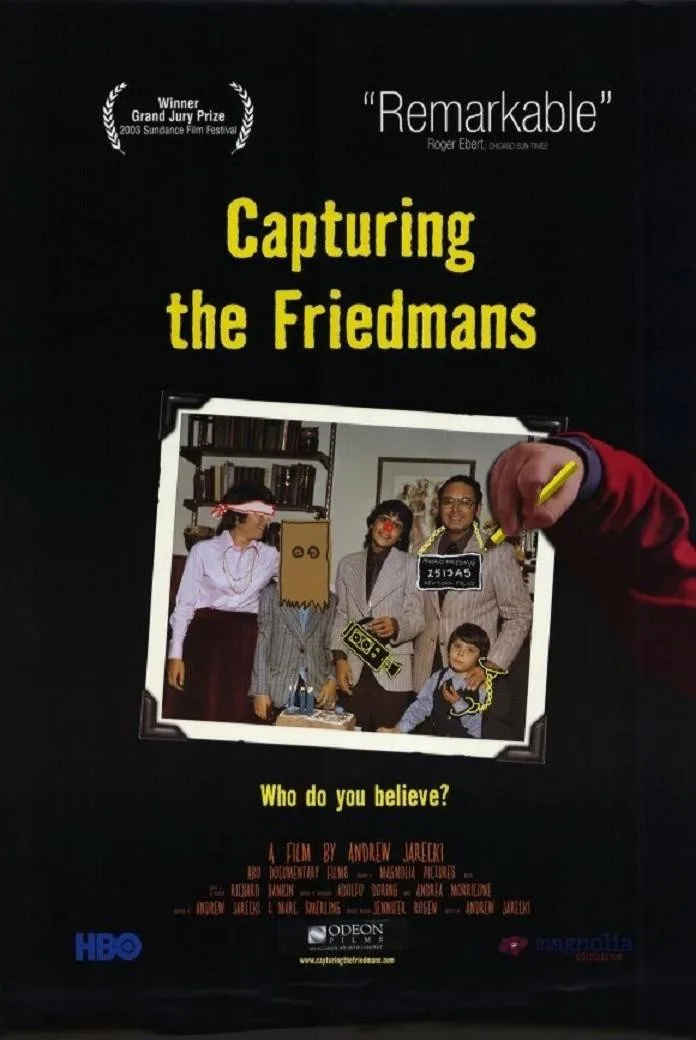

Featuring Arnold Friedman, David Friedman, Elaine Friedman And Jesse Friedman

After the Sundance screenings of “Capturing the Friedmans,” its director, Andrew Jarecki, was asked point-blank if he thought Arnold Friedman was guilty of child molestation. He said he didn’t know. Neither does the viewer of this film. It seems clear that Friedman is guilty in some ways and innocent in others, but the truth may never be known–may not, indeed, be known to Friedman himself, who lives within such a bizarre personality that truth seems to change for him from moment to moment.

The film, which won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance 2003, is disturbing and haunting, a documentary about a middle-class family in Great Neck, Long Island, that was torn apart on Thanksgiving 1987 when police raided their home and found child pornography belonging to the father. Arnold was a popular high school science teacher who gave computer classes in his basement den, which is where the porn was found–and also where, police alleged, he and his 18-year-old son, Jesse, molested dozens of young boys. Of the porn possession there is no doubt, and in the film Arnold admits to having molested the son of a family friend. But about the multiple molestation charges there is some doubt, and it seems unlikely that Jesse was involved in any crimes.

As Jarecki’s film shows the Friedmans and the law authorities who investigated their case, a strange parallel develops: We can’t believe either side. Arnold seems incapable of leveling with his family, his lawyers or the law. And the law seems mesmerized by the specter of child abuse to such an extent that witnesses and victims are coached, led and cajoled into their testimony; some victims tell us nothing happened, others provide confused and contradictory testimony, and the parents seem sometimes almost too eager to believe their children were abused. By the end of the film, there is little we can hang onto, except for our conviction that the Friedmans are a deeply wounded family, that Arnold seems capable of the crimes he is charged with, and that the police seem capable of framing him.

Our confusion about the facts is increased, not relieved, by another extraordinary fact: All during the history of the Friedmans, and even during the period of legal investigations, charges and court trials, the family was videotaped by another son, David. A third son, Seth, is visible in some of this footage but does not otherwise participate in the film. At the very time when Arnold is charged with possession of child porn, when the abuse charges make national headlines, when his legal strategy is being mapped, and his and Jesse’s trials are under way, David is there, filming with the privileged position of a family insider. We even witness the last family council on the night before Arnold goes to prison.

This access should answer most of our questions but does not. It particularly clouds the issue of Jesse’s defense. It would appear–but we cannot be sure–that he was innocent but pleaded guilty under pressure from the police and his own lawyer, who threaten him with dire consequences and urge him to make a deal. Given the hysteria of the community at the time, it seems possible he was an innocent bystander caught up in the moment.

The dynamics within the family are there to see. The mother, Elaine, who later divorced and remarried, seems in shock at times within a family where perception and reality have only a nodding acquaintance. She withdraws, is passive-aggressive; it’s hard to know what she’s thinking. Arnold is so vague about his sexual conduct that sometimes we can’t figure out exactly what he’s saying. He neither confirms nor denies. Jesse is too young and shell-shocked to be reliable. The witnesses contradict themselves. The lawyers seem incompetent. The police seem more interested in a conviction than in finding the truth. By the end of “Capturing the Friedmans,” we have more information, from both inside and outside the family, than we dreamed would be possible. We have many people telling us exactly what happened. And we have no idea of the truth. None.

The film is as an instructive lesson about the elusiveness of facts, especially in a legal context. Sometimes guilt and innocence are discovered in court, but sometimes, we gather, only truths about the law are demonstrated.

I am reminded of the documentaries “Paradise Lost” and “Paradise Lost 2: Revelations,” which involve the trials of three teenage boys charged with the murders of three children. Because the boys were outsiders, dressed in black, listened to heavy metal, they were perfect suspects–and were convicted amid hysterical allegations of “satanic rituals,” even while the obvious prime suspect appears in both films doing his best to give himself away. Those boys are still behind bars. Their case was much easier to read than the Friedman proceedings, but viewers of the films are forced to the conclusion that the law and the courts failed them.