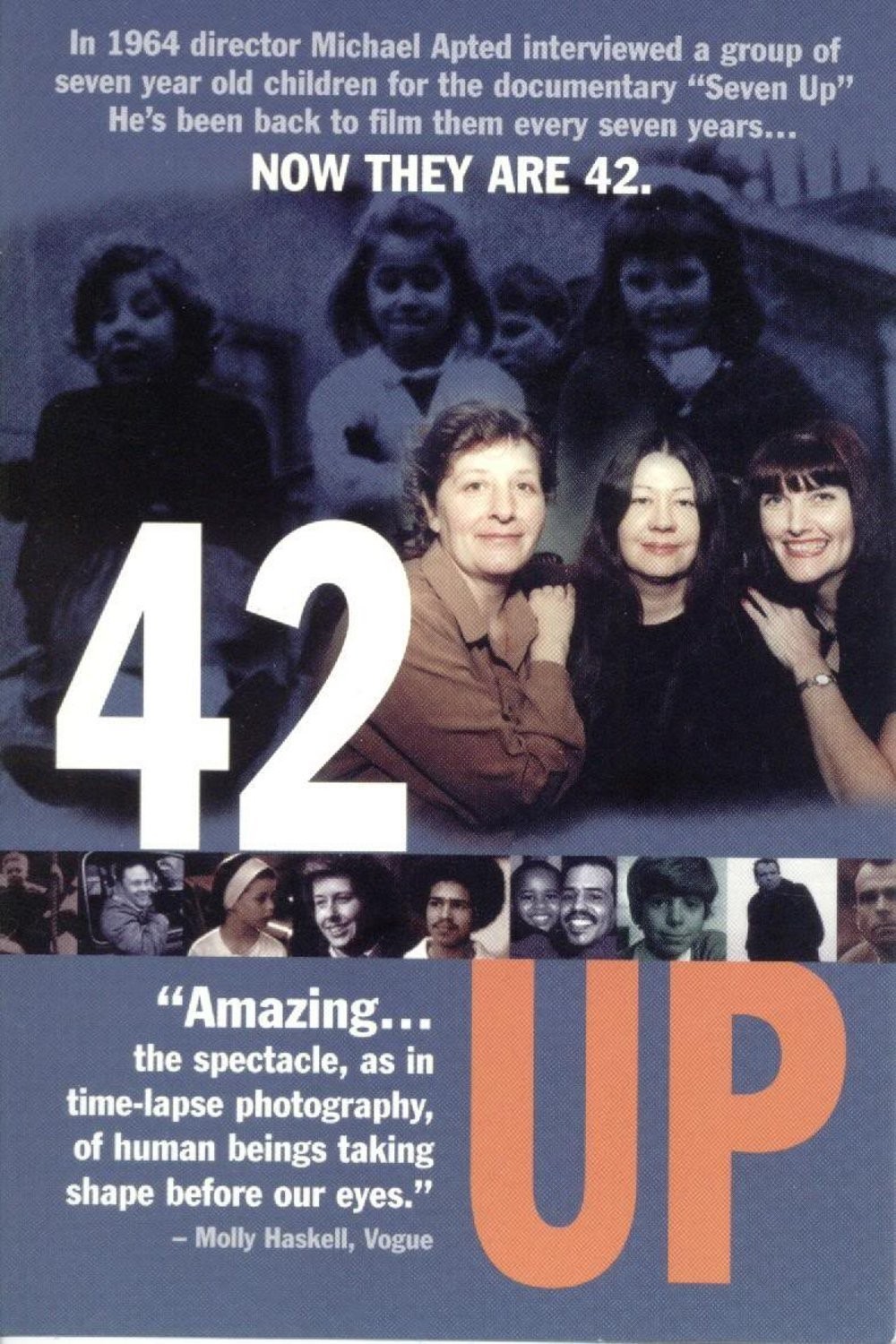

Now here is “42 Up,” the sixth installment in the series. I have seen them all since “14 Up,” and every seven years the series measures out my own life, too. It is impossible to see the films without asking yourself the same questions–without remembering yourself as a child and as a teenager, and evaluating the progress of your life.

I feel as if I know these subjects, and indeed I do know them better than many of the people I work with every day, because I know what they dreamed of at 7, their hopes at 14, the problems they faced in their early 20s, and their marriages, their jobs, their children, even their adulteries.

When I am asked for career advice, I tell students that they should spend more time preparing than planning. Life is so ruled by luck and chance, I say, that you may end up doing a job that doesn’t even exist yet. Don’t think you can map your life, but do pack for the journey. Good advice, I think, and yet I look at “42 Up” and I wonder if our fates are sealed at an early age. Many of the subjects of the series seemed to know at 7 what they wanted to do and what their aptitudes were, and they were mostly right. Others produce surprises, and keep on producing them right into middle age.

Michael Apted could not have predicted that his future would include a lifelong commitment to this series. He was a young man at the beginning of his career when he worked as a researcher on “7 Up,” choosing the 14 subjects who would be followed. He became the director of “14 Up” and has guided the series ever since, taking time off from a busy career as the director of feature films (“Coal Miner's Daughter,” “Gorillas in the Mist“).

In his introduction to a new book about the documentary series, Apted says that he does not envy his subjects: “They do get notoriety and it’s the worst kind of fame–without power or money. They’re out in the street getting on with their lives and people stop them and say, `Aren’t you that girl?’ or `Don’t I know you?’ or `You’re the one . . .,’ and most of them hate that.” The series hasn’t itself changed their lives, he believes. “They haven’t got jobs or found partners because of the film, except in one case when a friendship developed with dramatic results.” That case involves Neil, who for most longtime followers of the series, has emerged as the most compelling character. He was a brilliant but pensive boy, who at 7 said he wanted to be a bus driver so he could tell the passengers what to look for out the windows; he saw himself in the driver’s seat, a tour guide for the lives of others. What career would you guess for him? An educator? A politician? In later films he seemed to drift, unhappy and without direction. He fell into confusion. At 28, he was homeless in the highlands of Scotland, and I remember him sitting outside his shabby house trailer on the rocky shore of a loch, looking forlornly across the water. He won’t be around for the next film, I thought: Neil has lost his way. He survived, and at 35 was living in poverty on the rough Shetland Islands, where he had just been deposed as the (unpaid) director of the village pageant; he felt the pageant would be going better if he were still in charge.

The latest chapter in Neil’s story is the most encouraging of all the episodes in “42 Up,” and part of the change is because of his fellow film subject Bruce, who was a boarding school boy, studied math at Oxford, and then gave up a career in the insurance industry to become a teacher in London’s inner city schools. Bruce has always seemed one of the happiest of the subjects. At 40, he got married. Neil moved to London at about that time, was invited to the wedding, found a job through Bruce, and today–well, I would not want to spoil your surprise when you find the unlikely turn his life has taken.

Apted says in his introduction to the book 42 Up (The New Press, $16.95) that if he had the project to do again, he would have chosen more middle-class subjects (his sample was weighted toward the upper and working classes) and more women. He had a reason, though, for choosing high and low: The original question asked by the series was whether Britain’s class system was eroding. The answer seems to be: yes, but slowly.

Sarris, writing in the New York Observer, delivers this verdict: “At one point, I noted that the upper-class kids, who sounded like twits at 7 compared to the more spontaneous and more lovable lower-class kids, became more interesting and self-confident as they raced past their social inferiors. It was like shooting fish in a barrel. Class, wealth and social position did matter, alas, and there was no getting around it.” None of the 14 subjects have died yet, although three have dropped out of the project (some drop out for a film and are back for the next one). By now many have buried their parents. Forced to confront themselves at 7, 14, 21, 28 and 35, they seem mostly content with the way things have turned out. Will they all live to 49? Will the series continue until none are alive? This series should be sealed in a time capsule. It is on my list of the 10 greatest films of all time, and is a noble use of the medium.