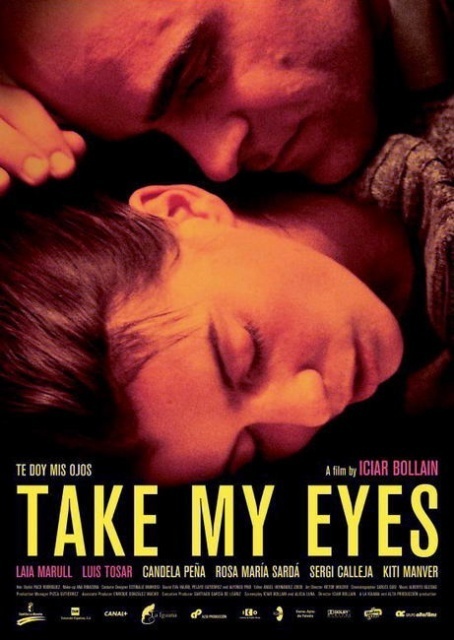

I knew a woman who stayed for years with a man who abused her. He couldn’t help himself. Neither could she. I think she was addicted to the excitement. She was the center of his world, the focus of his obsessions, the star of his disease. Some of the reviews of Iciar Bollain’s “Take My Eyes” can’t understand why Pilar returns to Antonio after his violent explosions. That’s the point of the movie: Logic becomes irrelevant when she’s caught in the drama. Just as he goes to therapy groups to learn how to guard against his anger, she flees to her sister to hear what a bastard Antonio is. Then some dread tidal force draws them together again.

The movie is not neutral. Pilar (Laia Marull) has a problem, but Antonio (Luis Tosar) has a much graver one. He is a sick man, whose insecurity and self-hatred boils up into violent outbursts against his wife. Even kicking a soccer ball around with his son, he finds himself kicking it too hard, thinking about his wife and taking it out on the kid. It is clear that Pilar should leave him and never return.

What makes the movie fascinating is that it doesn’t settle for a soap opera resolution to this story, with Pilar as the victim, Antonio as the villain, and evil vanquished. It digs deeper and more painfully. The film opens with Pilar desperately waking her young son, grabbing a few clothes, and fleeing in the night to the home of her sister Ana (Candela Pena). In a sane world, this would be the end of the story, with Pilar getting a protection order and Antonio forever out of the picture.

But he pleads to return. He promises to change. He goes into counseling and therapy. He talks sweet. Her deep feelings for the man begin to stir. We saw this process in “What's Love Got to Do with It” (1993), with Tina Turner finally breaking free from Ike. In “Take My Eyes,” which is about middle-class people in Toledo, Spain, the story is less sensational but trickier, because Antonio is a complex man. As we follow his attempts to reform, as we see that he’s really serious about controlling his anger, we begin to feel sympathy for him. We even pity him a little as we see how, step by step, his defenses fall, his lessons are forgotten, and rage once again controls him.

Pilar has not asserted herself much in the marriage, but now in a period of independence, she gets a job as a volunteer in an art museum, and quickly reveals an aptitude for talking about art. Soon she is a tourist lecturer; Antonio haunts the shadows of the museum, and as his wife describes the passions in paintings, he imagines she is focusing on men in her audience, sending them signals. She isn’t, but never mind: The point is that anything that Pilar does in the outside world, any skill she demonstrates or independence she shows, is a challenge to him. He cannot bear the possibility that she could live without him, could exist as herself and not as his possession.

The movie doesn’t go in for elaborate set-pieces of beatings and bloodshed. He is violent toward her, yes, but what’s terrifying is not the brutality of his behavior but how it is sudden, uncontrollable, and overwhelming. There is a time, after she has returned to him once again, where his anger grows and grows until finally he strips her down to a brassiere and shoves her out onto the balcony, to be seen by the neighbors, since after all that’s what she wants, isn’t it? To parade before strange men?

Laia Marull is powerful as Pilar, a woman who slowly, through hard lessons, is learning that she must leave this man and never see him again and not miss him or weaken to his appeals or cave in to her own ambiguity about his behavior. She may think (and some viewers of the film might think) that she is simply a victim, but when she returns to him, she gives away that game. She knows it’s insane, and does it, anyway.

As Antonio, Luis Tosar gives a performance comparable to Laurence Fishburne’s in “What’s Love Got to Do With It?” or Temuera Morrison’s in “Once Were Warriors” (1994). He makes his anger absolutely convincing, and that is necessary, or this is merely a story. The difference is that Marull’s Pilar is less confident, more implicated, than the strong women played by Angela Bassett and Rena Owen in the other two films. That creates a complex response for us. We sympathize at times with both characters, but curiously enough, we are more willing to understand why Antonio explodes than why Pilar returns to him. Surely she knows she’s making a mistake? Yes, she does. They both know they’re spiraling toward danger. If only knowledge had more to do with how they feel and why they act.