Jake Heke is a man with a hair-trigger temper, and its unpredictability is the most frightening thing about him. He likes to play the role of the genial, beer-swilling host, playing his guitar, singing songs, beloved by all, especially late at night by his drunken buddies. But let someone cross him, and he can lash out in the blink of an eye, the rage boiling over.

Jake and his wife, Beth, are Maoris, living in a housing development in New Zealand. They’re both good-looking people, and Jake, with his sunny, sleepy-eyed, self-satisfied smile, seems like he’s brimming with confidence. He is not. Beer fuels his resentments and insecurities, and masks his strength.

There is a scene early in “Once Were Warriors” where he gets into a fight in a bar and inflicts incredible damage on a muscle-bound thug who seemed, until he met Jake, able to whip anybody in sight. This is a key scene because it establishes what Jake is capable of; all through the movie, we are waiting for that violence to be unleashed again.

“Once Were Warriors” shows Jake and Beth in good times and bad.

They flirt, they sing boozy duets, they make love. But Jake is also capable of turning in a flash into a brutal monster, and Beth wakes up one morning with her face a bloody mass of bruises. “It’s the same old story,” she tells a friend. “I’ve got to learn to keep my mouth shut.” During the course of “Once Were Warriors,” she will slowly learn to stop blaming herself when she gets beaten.

Beth has a temper, too. Booze is the problem in the household, triggering terrifying personality changes. The kids learn to stay out of the way, especially the older ones: Boogie, the boy, who joins a gang, and Grace, a beautiful teenager, who retreats into her journal and into a friendship with a spaced-out boyfriend who lives with his drugs in an abandoned car. Huddled in their room one night with the sounds of anger crashing through the walls, Grace explains to her brother: “People show their true feelings when they’re drunk.” The movie has carved a reputation for itself on the festival circuit, leaving audiences shaken and silent at Telluride, Toronto, Honolulu and Park City. It is powerful and chilling, and directed by Lee Tamahori with such narrative momentum that we are swept along in the enveloping tragedy of the family’s life.

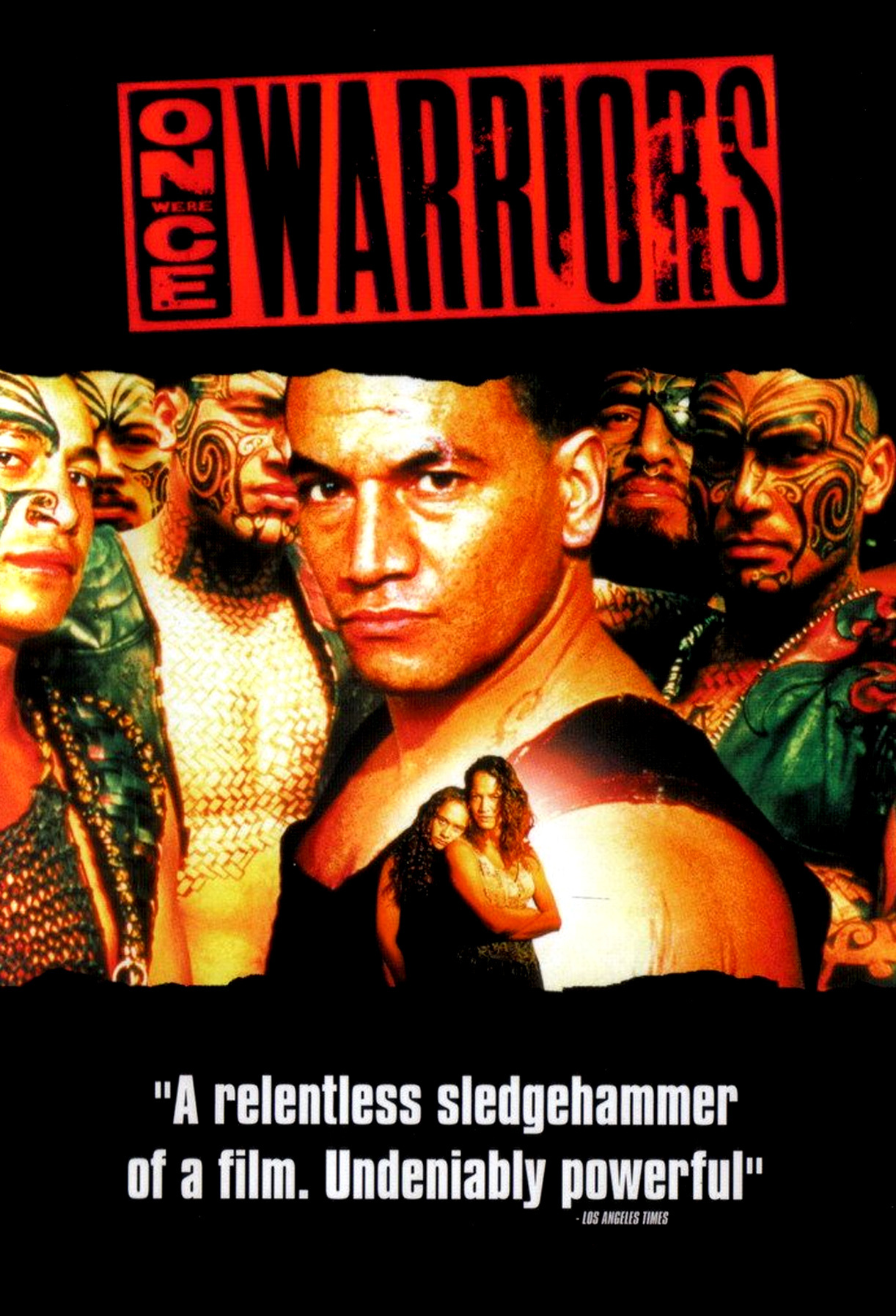

In Temuera Morrison, as Jake, the movie finds a leading actor as elemental, charismatic and brutal as the young Marlon Brando; he has instinctive star power, and it’s his likability that makes the violence of his character so shocking. Rena Owen, as Beth, supplies the moral center of the film, as a woman who finally calls a halt to the spiral of pain in her family.

The director’s key achievement is creating a convincing sense of daily life in the household and neighborhood. This is not a narrow drama that focuses on a few themes; it paints a whole style of life, the good times with the bad, and perhaps no scene is more sad than the one in which the family rents a car and sets off on a picnic, happy and in good spirits, only to have everything go wrong when Jake decides to stop for just one drink.

Mamaengaroa Kerr-Bell, as Grace, the pretty teenager, is also important to the film; she reflects a hope and optimism that somehow shines even on the family’s cloudiest days, and although her runaway boyfriend’s hideout under an expressway seems grim, they are able to make it into a refuge where laughter and dreams are possible.

Then everything goes bad for them, too.

“Once Were Warriors” has been praised as an attack on domestic violence and abuse. So it is. But I am not sure anyone needs to see this film to discover that such brutality is bad. We know that. I value it for two other reasons: its perception in showing the way alcohol triggers sudden personality shifts, and its power in presenting two great performances by Morrison and Owen. You don’t often see acting like this in the movies. They bring the Academy Awards into perspective.