“Tadpole” tells the story of a bright 15-year-old who has a crush on his stepmother and actually sleeps with her best friend, in part because the friend is wearing the stepmother’s scarf and the lad is powerless over the evocative lure of her perfume. The sexual excursion is not the point of the movie, really, but the set-up for its central scene in which young Oscar has dinner with his father, his stepmother, and the friend, who wickedly threatens to reveal their secret.

Watching the movie at Sundance in January, I tried to accept this premise on its own terms, but could not. Too much has happened in the arena of sexual politics since “The Graduate,” and I kept thinking that since Oscar was 15 and his stepmother and her friend were about 40, this plot would have been unthinkable if the genders had been reversed. The best friend, far from teasing the new sexual initiate with exposure, would have been terrified of arrest, conviction and a jail sentence for statutory rape.

I am, I realize, hauling political correctness into a movie where it is not wanted. I know there is even a lighthearted mention of the laws involved. I know I praised “Lovely & Amazing,” which also features a romance between an adult woman and a teenage boy. But “Lovely & Amazing” is about events that happen in a plausible world (the adult is actually arrested). “Tadpole” wants only to be a low-rent “Graduate” clone.

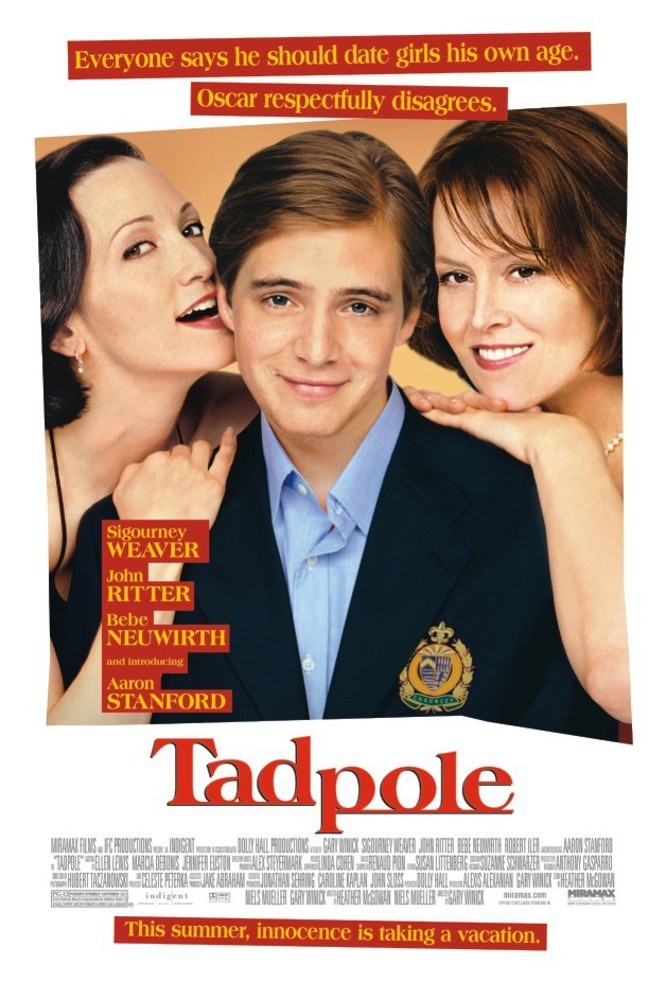

Does it succeed on that level? Not really. True, the dinner scene has its moments, as Oscar (Aaron Stanford) squirms, his lover Diane (Bebe Neuwirth) grins wickedly, his stepmother Eve (Sigourney Weaver) keeps up the conversation, and his father Stanley (John Ritter) practices a suave cluelessness which is his strategy for dealing with life. Neuwirth is really very good here, and the scene supplies the one moment when the movie seems sure of what it wants to do, and how to do it.

The rest of the movie seems perfunctory and derivative, and although I could believe that Oscar would find Eve attractive, I could not quite believe the labored conversations they have, in which he is talking on one level and she on another. It was even less credible that Eve, for a split-second, actually seems to be considering Oscar’s desire seriously.

The movie, directed by Gary Winick and written by Heather McGowan and Niels Mueller, gives us Woody Allen’s “Manhattan” crossed with Whit Stillman’s affluent preppies. Like Stillman’s “Metropolitan,” “Barcelona” and “The Last Days of Disco,” it gives us a hero who is articulate, multi-lingual, sophisticated beyond his years, and awesomely self-confident. The difference is that Stillman was seriously intrigued by his young characters, and “Tadpole” uses Oscar primarily as an excuse for transgressive lust.

If Oscar were not forever speaking French and quoting Voltaire, we might see his passion for what it is, the invention of the filmmakers. I never really believed Oscar lusted after Eve the woman, but only after Eve the plot point–the archetypal older woman descended in an unbroken line from “Mrs. Robinson.” The film has other problems than credibility. It ends with unseemly haste, it underlines its points too obviously, and its camera moves when it should be still. Some of the flaws may be excused by the filming method; “Tadpole” was filmed in two weeks for about $150,000, and the cast and crew took the minimum wage. When the film played at Sundance, there was a lot of buzz and Winick won the prize as best director. But there was also talk that the digital photography was noticeably washed-out. When Miramax bought the film (for a rumored but no doubt inflated $6 million), word was that the studio would give the visuals an overhaul. They still look unconvincing.

I am reminded of what Gene Siskel used to say whenever a hopeful director told him how little a movie cost. Gene would nod and reply, “I wish you had made it for more.” I am in favor of low-budget filmmaking, but I do not consider it a virtue in itself, only a means to an end. In the case of “Tadpole,” the hurried schedule, the shaky digital video and the lack of character development may all be connected to the fast, cheap shoot. A longer movie (this one is barely feature length at 77 minutes) might have made the relationships more nuanced and convincing. In this version, we can sense the machinery beneath the skin.