Movies about political movements tend to have one of two problems: 1.) The film views the events through the filter of one individual’s experience, narrowing the scope. 2.) The film takes a rote, careful approach, sacrificing emotional complexity.

“Suffragette,” detailing the push for women’s suffrage in the United Kingdom in 1911-13, has both of these problems, although it suffers more from the first. Directed by Sarah Gavron and written by Abi Morgan, “Suffragette” makes it look like because one (fictional) woman (Carey Mulligan) testified about her hardships to future Secretary of State for War Lloyd George, the suffrage movement experienced a depth-charge of commitment. In reality, the movement was a fractious and divided affair (and, incidentally, far more interesting than one mousy woman deciding to get involved).

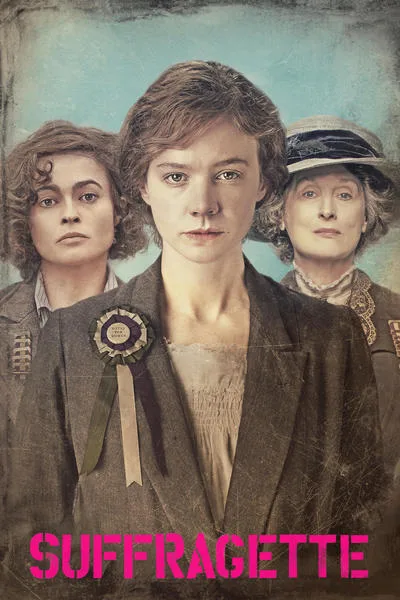

Maud (Mulligan) lives with her husband and son and works in a laundry, a hotbed of deplorable conditions, low wages, and sexual assault. A co-worker named Violet (Anne-Marie Duff) encourages Maud to come to secret meetings run by Edith and Hugh Ellyn (Helena Bonham Carter and Finbar Lynch). Maud gets sucked in. She is arrested and then released, a pattern that will continue, although the incarcerations grow brutal, involving hunger strikes and the barbaric practice of forcible feeding. A cop (Brendan Gleeson) doesn’t think much of women’s suffrage, and yet is concerned about Maud: he sees working-class women being used as “fodder,” taking risks that the upper-class women refuse to take. He is not wrong, nor is he entirely unsympathetic. Gleeson brings a welcome layer to the film.

Shot mostly handheld (the cinematographer is the talented Eduard Grau, whose last film was Joel Edgerton’s “The Gift”), “Suffragette” feels like a documentary in its visuals, but at the same time drowns in subjectivity (Maud’s face in repeated closeup). The peripheral (where the good stuff happens) is barely perceived. It’s telling that the most moving passage in “Suffragette” is newsreel footage of a real event.

“Suffragette” includes the events known by anyone familiar with the history: hunger strikes, bombs dropped into mailboxes, the blowing up of Lloyd George’s summer home. A turning point was in 1913, when Emily Wilding Davison (played in the film by Natalie Press) stepped out in front of King George’s galloping horse on Derby Day, a “Votes for Women” banner in her hand, and was trampled to death. A martyr. Thousands of people lined the streets to watch the funeral procession. It’s all in “Suffragette,” but you keep wanting to move Maud out of the way so you can get a better view.

Meryl Streep appears once as Emmeline Pankhurst, the movement’s figurehead. Pankhurst, wanted by the police, comes out of hiding to make a speech from a balcony. In a 1933 article, Rebecca West (suffragette, journalist, and, near the end of her life, one of the “witnesses” in Warren Beatty’s “Reds“), referred to Pankhurst as a “reed of steel.” Streep, in the two minutes (tops) she’s on-screen, places a genteel overlay of breeding in her ringing hoity-toity voice, but her speech is filmed in such a haphazard way that what it ends up being about is her gigantic hat.

Bonham Carter, on the other hand, strolls into “Suffragette” and steals it from under Mulligan’s nose. Edith is a pharmacist in a good marriage, who decides to break the laws that were passed without her consent or vote. She is physically fragile but emotionally indomitable. Mulligan’s work seems unfocused and moist, in comparison. For example, in one scene, Lloyd George (Adrian Schiller) informs a gathering of women that the suffrage bill did not pass. The women feel betrayed (they thought he was an ally) and shouts of “Liar!” fill the air. Mulligan shouts “Liar” and there’s nothing going on beneath her face. Her expression is flat, it leads nowhere. Meanwhile, next to her, Bonham Carter shimmers with rage and a practical tight-lipped determination. She is dogmatic and fearless, the embodiment of a “reed of steel.”

Recently, “Stonewall” received criticism for showing the Stonewall Riots through the eyes of a fictional white boy, when those riots were instigated by mostly black and Latina protesters, people whose names are already in the history books. “Suffragette” has a similar problem. These real people are heroes. Let them star in their own stories. Compare to Warren Beatty’s “Reds,” which had a personal story, featuring the real-life people, and which also managed to show the divides in the American Left, the factions and the unpredictable alliances, without sacrificing emotion or depth. Or Ava DuVernay’s “Selma,” with its ideological clashes, fights over the best approach and portraits of the diverse real-life figures involved: students, women, preachers, laymen. Films like “Reds” or “Selma” have a willingness to tolerate complexity. Complexity is part of the struggle. There are moments in “Suffragette” that try (some women back out when bombs are discussed), but the focus on Maud, and her personal situation, diminishes the movement.

As with many movements, groups were excluded initially: working-class women, women of color, single women, and those who deviated from mainstream dogma. “Suffragette” ends with a roll of dates showing when various nations gave women the vote. In America, all women were enfranchised in 1920, but state laws and intimidation kept black women out of the voting booth in many areas until decades later. It’s a glaring omission, and, again, shows an unwillingness to live in the rich complexity of reality.