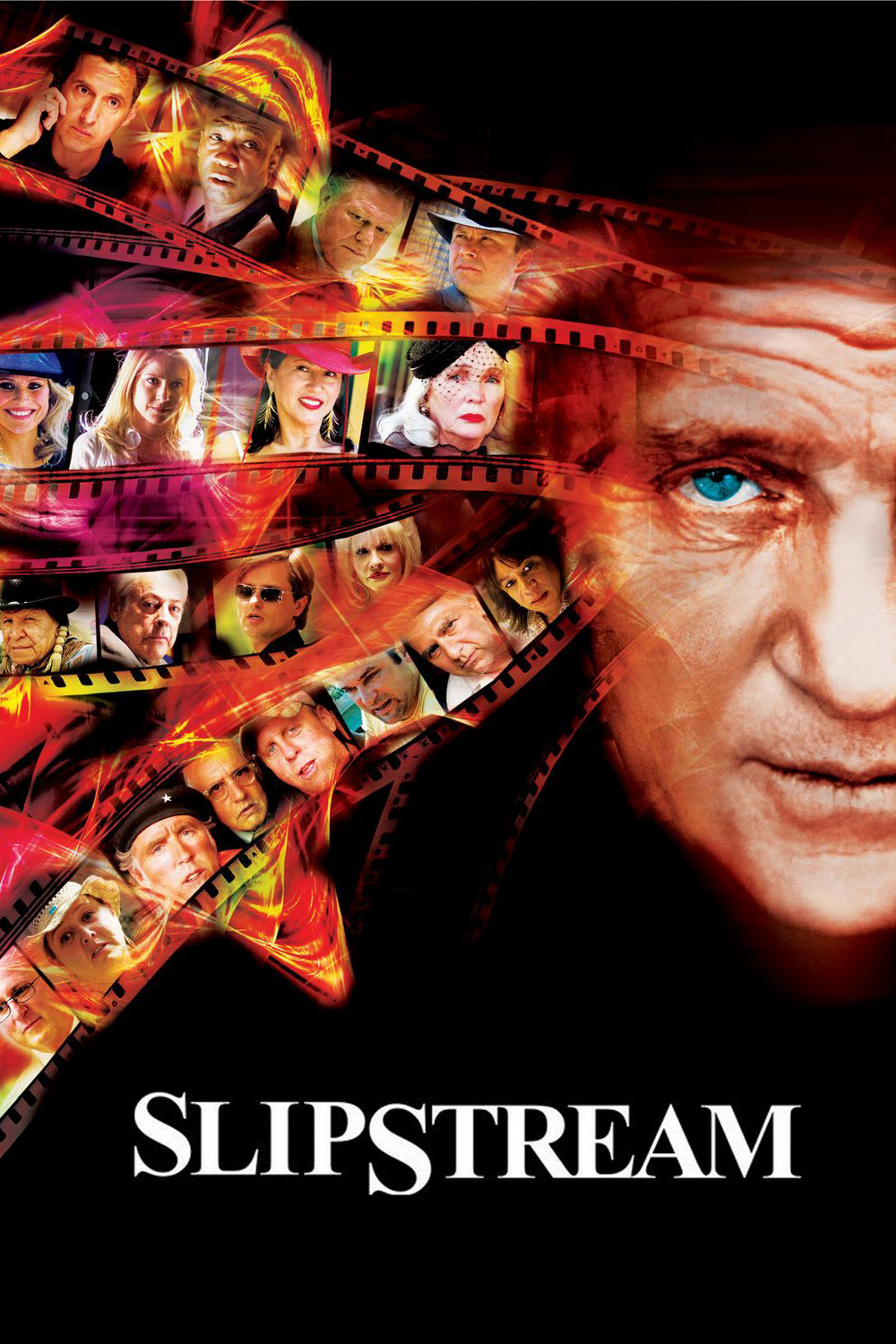

Leave it to a 69-year-old actor to make the year’s most experimental film. Anthony Hopkins’ “Slipstream” is an attempt to represent what goes through the mind of a dying man, although you wouldn’t guess that from its official plot summary on the Internet Movie Database, which thinks it’s about a screenwriter “on the verge of implosion.” So have I revealed a plot point? No, because it’s clearly stated in the movie’s first line of dialogue and repeated in the last.

I have grown so wise, however, only after viewing the movie a second time. When I wrote my interview with Hopkins (which appeared Sunday), I shared the general opinion: Felix, the writer in the film, I wrote, “is confusing reality with illusion. His characters appear in his life, his life appears in the movie, and mostly he looks on uncertainly while both real and imaginary people do all the loving, living and dying.” All true enough in a way, but beside the point.

There is no direct line through the story, which creates the way a man might think if he had received a sudden shock, was under heavy sedation, and was combining recent experiences with current ones. He doesn’t confuse his fictional characters with real people; he sees them interchangeably. Let’s say he based a character on his wife (Stella Arroyave). Sometimes the character looks like his wife, sometimes his wife looks like the character, sometimes he thinks she’s in the room, sometimes he thinks she’s on the set, sometimes he thinks they’re together in a third place. It’s dream logic, and the movie offers a clue by quoting Edgar Allan Poe:

All that we see or seem

Is but a dream within a dream.

In the overarching action of the movie, Felix has written a screenplay that is being filmed in the Mojave Desert. Gavin Grazer, who plays the director, is said to have a big-shot producer brother whose shadow he tries to escape. Indeed, Gavin is the brother of big shot producer Brian Grazer, and that’s the kind of connection that might occur in the screenwriter’s mind and be assigned as a throwaway line to a character in his fantasy.

The movie within the movie involves a couple of tough guys (Christian Slater and Jeffrey Tambor) who terrorize a roadside diner after Slater has put a bullet into the head of a bartender (Michael Clarke Duncan). The diner scene owes much to old crime movies; Felix has lived those movies so intently that one of his favorites, the original “Invasion of the Body Snatchers,” produces the real Kevin McCarthy, who Felix imagines he is driving with through the desert.

Later imaginations fill his computer screen with a screaming studio boss (John Turturro) who is allegedly inside his hard drive, and there are shots in which Duncan (head still oozing with blood) and the movie’s continuity girl (Camryn Manheim) complain to him that their characters have not only been killed, but shortchanged on some of their lines. One of the movie’s most natural examples of dream logic is when Felix asks a Dolly Parton lookalike her name, and she replies, “Dolly Parton Lookalike.” Of all the characters, the only one who doesn’t seem to fall into dreaminess is the waitress played by S. Epatha Merkerson, maybe because she is the most like who she really is.

Now is “Slipstream” worth seeing? I think so, if you’ll actively engage your sympathy with Hopkins’ attempt to do something tricky and difficult. If you want to lie back and let the movie come to you, you may be lying there a long time.

But I think Hopkins does an impressive job of creating the kind of dream-drug-reverie state people can go through. I trust you enough, dear reader, to tell you something I should keep private: During a period after my surgical emergency, when I was on what Mr. Limbaugh so usefully describes as prescription medications, I had dreams more real than my waking moments. Then the fog cleared, my health returned, the medication stopped, and I resumed writing brilliant and lucid reviews like this one. But I know Hopkins gets it right, because I’ve been there. What he gets right is made clear at the end. No, I do not refer to the last appearance of the red convertible, but to the sequence following that, and then the closing dialogue.

Hopkins himself has wisely declined to “explain” his film, going so far at Sundance as to say “I did it as a little joke.” That’s the thing about Brits (and Welsh, in this case). They tend to be pathologically modest and understatement is their style. Let’s apply the statement “I did it as a little joke” to “Grindhouse,” a recent film that was done as a little joke, and see how the same dialogue would translate into the speech of an American director, such as Quentin Tarantino: “This isn’t some ‘Twilight Zone the Movie’ f*****g thing. This is not a faux double feature. This is two f*****g movies for the price of one! Your $10 will be well spent at ‘Grindhouse,’ baby!”

And perhaps as well spent at “Slipstream,” although the two films have been made for altogether different audiences, and I anticipate little overlap.