“Shoah: Four Sisters,” a quartet of features interviewing female Holocaust survivors, is the final project by documentary filmmaker and historian Claude Lanzmann, who died this past summer at 92. Built mainly from footage that Lanzmann did not use in his landmark, nearly nine-hour 1985 documentary “Shoah,” the films exist in an aesthetic grey area, somewhere between outtakes, old fashioned DVD supplements, and alternate cuts. Maybe it’s best to think of them as hypertext links within the wider context of the director’s masterpiece. Click on them, and you go to a separate, self-contained piece that tells one story at length.

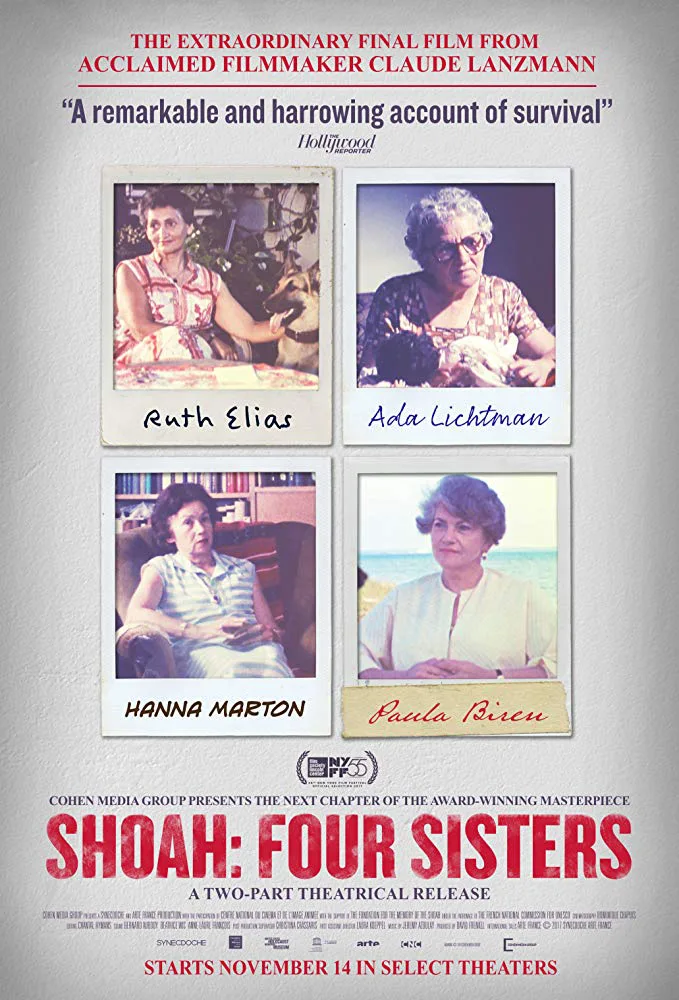

Lanzmann interviewed the four women—Ruth Elias, Paula Biren, Ada Lichtman, and Hannah Marton—for “Shoah” in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Two of them were featured more briefly in the original “Shoah.” These new films are titled “Baluty,” “The Merry Flea,” “The Hippocratic Oath,” and “Noah’s Ark.” Moral compromise, or the fear of it, dominates all four stories, along with a powerful (though at times suppressed) sense of survivor’s guilt.

Biren talks about living in the Lodz ghetto in Poland; she grapples with regret over working with a Jewish women’s police force and, at one point, assisting in the possible deportation of a peddler. Marton consults her husband’s World War II diary as she tells of her escape to Palestine on a train, along with over 1600 other Jews whose release was secured by Rezso Kasztner via negotiations with Adolph Eichmann. Lichtman describes how the Germans made her clean and dress dolls seized from Jewish children to be passed on to their own kids. Elias talks about surviving both the Theresienstadt camp and Auschwitz despite being eight months pregnant, a narrative that builds to a peak of almost unbearable dread.

Running somewhere between 60 and 90 minutes each, these movies continue the stripped-down approach of “Shoah,” and escalate it in some ways. Lanzmann can be seen onscreen listening, smoking, and asking questions (and in one case, walking alongside a subject as they talk on a beach). He concentrates on the women as they tell their stories, cutting to photographs rarely, and to archival footage never. Sometimes we stare at a woman’s face in a static shot for several minutes without an edit. The only visual change occurs when the movie cuts to Lanzmann reacting, or subtly zooms in or out to capture an emotion or magnify the intensity of a moment.

Some viewers of Lanzmann’s work, including staunch admirers, have wondered if what he’s doing in these movies is really “filmmaking” as we traditionally understand it, or something more along the lines of skillful interviewing that happens to be recorded. The filmmaking here, more so than even in “Shoah,” should put that to rest. This is minimalist directing of a high order, practically invisible in its choices and effects, but repeated so often that it seems unquestionably indicative of a very particular style—one that aims to create the conditions necessary to birth a compelling though understated remembrance of unimaginable pain. The story is shaped in the process of recording it, rather than being excessively manipulated after the fact.

The women are all compelling though never too-polished storytellers. Whether they succumb to the horror of what they’re describing and start to cry or remain stoic throughout becomes part of the experience of hearing the tale. The incidental location sound that can be heard in the background of interviews (such as barking dogs, or the crash of waves at the beach) becomes a part of the story—an audio bridge between the past being described, and the future that Lanzmann and his interview subject could not have foreseen 40-some years ago.

Even without a lot of cuts for time, each story is perfectly paced, and filled with little details that big-picture histories tend to miss, such as the remembered sounds and smells and textures of a place, or the look in the eye of a menacing or doomed person that the storyteller met briefly but remembered always. The zooms that bring us closer to a speaker or give her a bit of space are unerringly timed and rarely seem intrusive or garish, as they often do on television news segments. It’s as if the filmmaker, the storyteller and the audience have fused to bear witness.

Each film could stand on its own, but there’s something to be said for viewing them all as closely together as possible, so that the total running time is about half that of “Shoah.” Lanzmann’s approach captured the Holocaust as a living memory at a time when the youngest survivors were moving into middle age and the elders were starting to die off. Now, nearly 75 years from the end of World War II and the liberation of the concentration camps, the interviews themselves have passed from living memory, becoming something that the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the Holocaust remember from childhood stories, and that they hope the larger culture will remember, too.