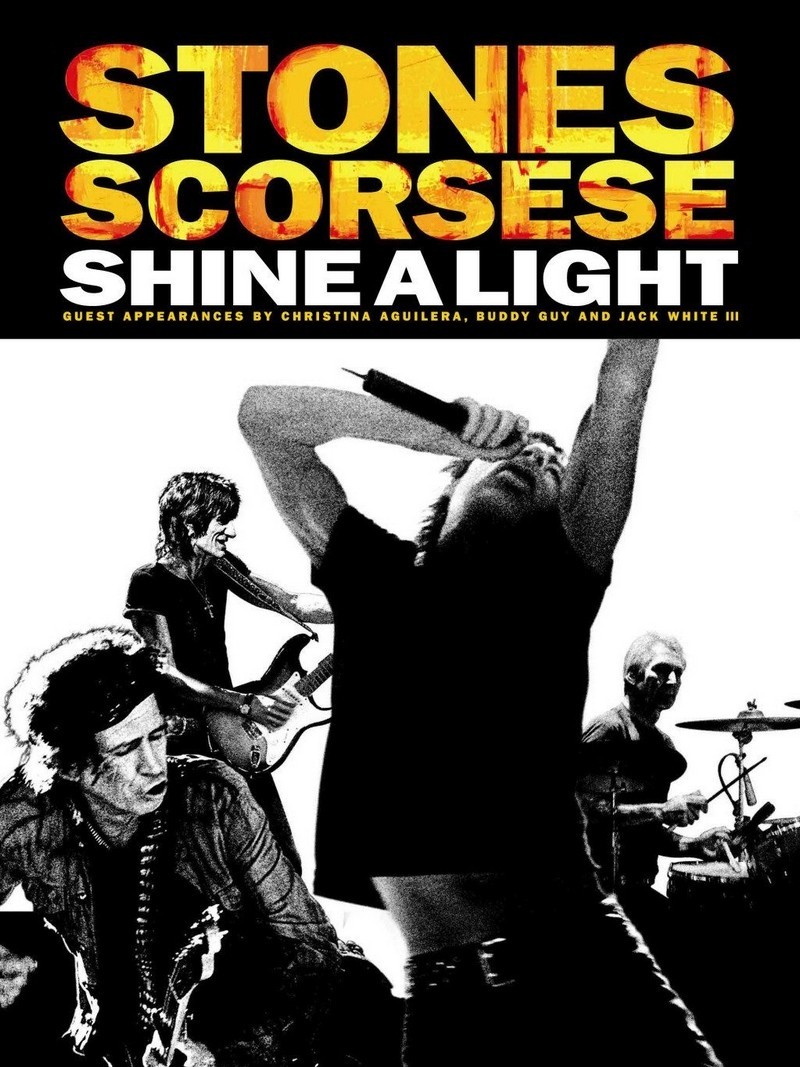

Martin Scorsese’s “Shine a Light” may be the most intimate documentary ever made about a live rock ‘n’ roll concert. Certainly it has the best coverage of the performances onstage. Working with cinematographer Robert Richardson, Scorsese deployed a team of nine other cinematographers, all of them Oscar winners or nominees, to blanket a live September 2006 Rolling Stones concert at the smallish Beacon Theatre in New York. The result is startling immediacy, a merging of image and music, edited in step with the performance.

In brief black-and-white footage opening the film, we see Scorsese drawing up shot charts to diagram the order of the songs, the order of the solos, and who would be where on the stage. This was the same breakdown approach he used with his doc “The Last Waltz” (1978), which would hopefully enable him to call his shots through earpieces of the cameramen, as directors of live TV did in the early days. The challenge this time was that Mick Jagger toyed with the list in endless indecision; we look over his shoulder at titles scratched out and penciled back in, and hear him mention casually that of course the whole set might be changed on the spot. Apparently after playing together for 45 years, the Stones communicate their running order telepathically.

In a sense, this movie marks where Scorsese came in. I remember visiting him in the post-production loft for “Woodstock” in 1970, where he was part of team led by Thelma Schoonmaker who were combining footage from multiple cameras into a split-screen approach that could show as many as three or four images at once. But the Woodstock footage they had to work with was captured on the run, while “The Last Waltz” had a shot map and outline, at least in Scorsese’s mind. “Shine a Light” combines his foreknowledge with the versatility of great cinematographers so that it essentially seems to have a camera in the right place at the right time for every element of the performance.

It helped, too, that the Stones’ songs had been absorbed by Scorsese into his very being. “Let me put it this way,” he said in a revealing August 2007 interview with Craig McLean of the London Observer. “Between ’63 and ’70, those seven years, the music that they made I found myself gravitating to. I would listen to it a great deal. And ultimately, that fueled movies like ‘Mean Streets’ and later pictures of mine, ‘Raging Bull’ to a certain extent and certainly ‘GoodFellas’ and ‘Casino’ and other pictures over the years.”

Mentioning that he had not seen the Stones in concert until late 1969, he said the music itself was ingrained: “The actual visualization of sequences and scenes in ‘Mean Streets’ comes from a lot of their music, of living with their music and listening to it. Not just the songs I use in the film. No, it’s about the tone and the mood of their music, their attitude. I just kept listening to it. Then I kept imagining scenes in movies. And interpreting. It’s not just imagining a scene of a tracking shot around a person’s face or a car scene. It really was [taking] events and incidents in my own life that I was trying to interpret into filmmaking, to a story, a narrative. And it seemed that those songs inspired me to do that, to find a way to put those stories on film. So the debt is incalculable. I don’t know what to say. In my mind, I did this film 40 years ago. It just happened to get around to being filmed right now.”

The result is one of the most engaged documentaries you could imagine. The cameras do not simply regard the performances; in a sense, the cameras are performers too, in the way shots are cut together by Scorsese and his editor, David Tedeschi (who also edited “The Last Waltz”). Even in their 60s, the Stones are the most physical and exuberant of bands. Compared to them, watching the movements of many new young bands on Leno, Letterman and “SNL” is like watching jerky marionettes.

Jagger has never used the mechanical moves employed by many lead singers; he is a dancer and an acrobat, and a conductor, too, who uses his body to conduct the audience. In counterpoint, Keith Richards and Ron Wood are loose-limbed, angular, like way-cool backup dancers. Richards in particular seems to defy gravity as he leans so far over; there’s a moment in rehearsal when he tells Scorsese he wants to show him something, and leans down to show that you can see the mallet of Charlie Watts’ bass drum, visible as it hits the front drumhead. “I can see that because I’m down there,” he explains.

The unmistakable fact is that the Stones love performing. Watch Ron lean an arm on Keith’s shoulder during one shared riff. Watch the droll hints of irony, pleasure, quizzical reaction shots, which so subtly move across their seemingly passive faces. Notice that Keith does not smoke onstage not simply to be smoking, but to use the smoke cloud, brilliant in the spotlights, as a performance element. He knows what he’s doing. And then see it all brought together and tied tight in the remarkably acrobatic choreography of Jagger’s performance. I’ve seen the Stones in Chicago in venues as large as the United Center and as small as the Double Door, but I’ve never experienced them this way, because the cameras are as privileged as the performers onstage.

And the music? What do I have to say about the music? What is there left to say about the music? In that interview, Scorsese said, “‘Sympathy for the Devil’ became this score for our lives. It was everywhere at that time, it was being played on the radio. When ‘Satisfaction’ starts, the authority of the guitar riff that begins it is something that became anthemic.'”

I think there is nothing useful for me to say about the music, except that if you have been interested enough to read this far, you already know all about it, and all I can usefully describe is the experience of seeing it in this film.