When Steven Soderbergh announced he was retiring from cinema, he lamented about seeing a fellow passenger on an airplane watch only the action scenes in a list of loud movies, skipping the dialogue and story. The director called this “mayhem porn,” a designation and ideology fitting for the latest from indie director Mickey Keating, “Psychopaths.” The film is an active, obnoxious test of an audience’s appetite for blood and how long they can go without novel ideas like purpose or plot.

In the history of lazy conceits for mass violence, “Psychopaths” proudly throws itself towards the bottom. A serial killer (played by horror icon Larry Fessenden, who also executive produced) has just been executed, and the evil within his soul has spread throughout Los Angeles. Not in any direct visual way, but enough so that this script can focus on violence as a type of trending topic for the night.

“The Purge” films, of which “Psychopaths” will owe many of its viewers, nudge that violence is an epidemic that we choose to embrace. But any idea of treating “Psychopaths” as a type of commentary on how violence is a force beyond consciousness is muffled early, as violence becomes an action to create whatever “Psychopaths” thinks looks cool. Overhead shots of torture weapons, shadowy long takes of people being shot in darkness—it’s all just about killing people for the sake of killing people. Ho hum.

A plot does not materialize so much as characters of questionable backgrounds and expansive capacities for violence. In an elegantly composed one-shot, a man is introduced attacking a woman, strangling her, and killing someone that comes to the rescue. Played by James Landry Hebert and a distinct mustache, he’s known as The Strangler, naturally. But the night has other things in store for him when he meets Blondie (Angela Trimbur), a killer of her own right, with her own stone face and campy desire to torture.

Evil lurks elsewhere in the valley, like in the soul of a singer named Alice (Ashley Bell, a Keating MVP), who is introduced with a brightly-lit stage performance of “Let Me Call You Sweetheart.” She turns out to be a psychopath too, indicated by a schizophrenic, fourth wall-breaking monologue that fluctuates between her normal voice and one of a demon. Later on, she attacks a quaint yet quarreling suburban couple. For a movie that essentially has its production design done by Halloween, her hamminess is more spirited than most character flourishes here.

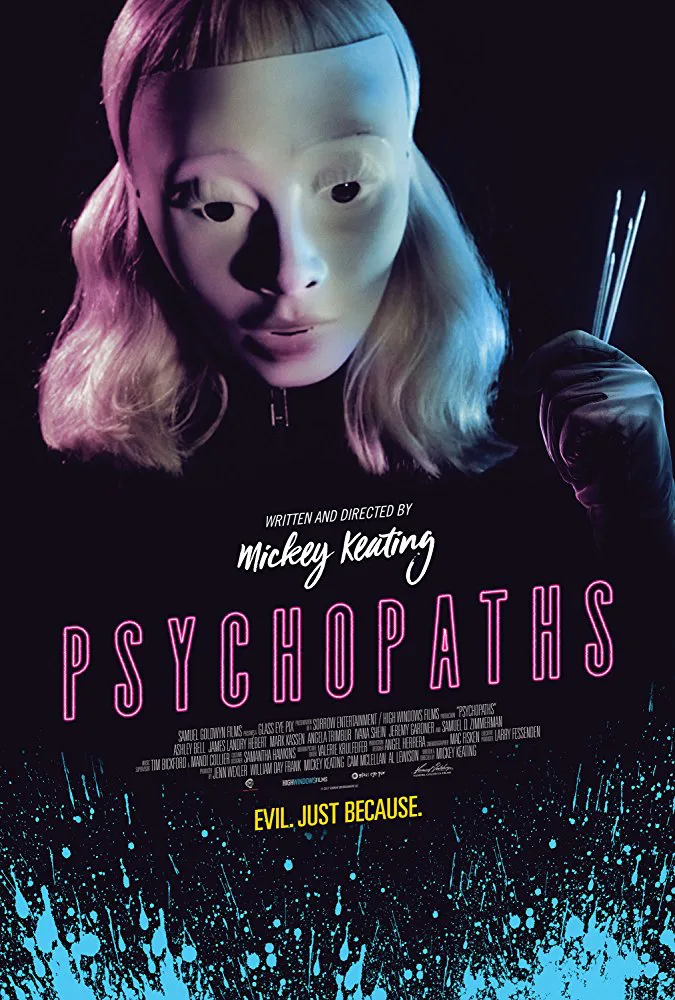

And yes, given that this is a movie about psychopaths, there are some killers in masks, some of their violence involving the weak script idea of revenge. But as a character shrugs in the script, fitting with the film’s middle school-level interest in wisdom: “There ain’t no why to evil.”

All this carnage is loosely connected, sometimes with different attacks spliced back and forth, but the stakes are zilch. Characters, whether considered to be psychopaths or not, are treated with the care of blood bags that exist simply to explode, if not before a menacing soundtrack needle-drop or rambling monologue. For whatever inspiration “Psychopaths” has, as a type of chaos so pure that it lacks substance, it drags. To call it an “experiment” would be to acknowledge that it has a purpose.

“Exercise” might be a better word, however, as Keating is truly an accomplished composer with the instruments of filmmaking. There is a precision in framing, color, lighting, parallel editing and even sound mixing that makes “Psychopaths” more digestible than its screenplay would suggest. Whatever the hell is happening on screen or whoever is being cut up or mutilated, the film is built from dedication.

But unless the ambition of “Psychopaths” is to motivate Michael Haneke to remake “Funny Games” for a second time, its efforts are gravely misplaced. The self-aware conceits of Keating’s film get it nowhere, except farther away from having any major impact. At its best, “Psychopaths” is an empty rebellion of a genre movie. At its worst, it’s a confounding piece of shiny trash.