I met her near the beginning, at Cannes, sitting on the lawn of a villa sloping down toward the sea. It was 1977, the year Isabelle Huppert made “The Lacemaker.” She was 24, had already made more than a dozen features, starting at 17. She told me how that happened: “I walked up to the studio door in Paris, knocked, and said, ‘I am here.’ ” She was. She has a quiet confidence that is almost terrifying.

Thirty years later at 54, but looking no age at all in particular, she has made 89 film and television projects. She works all the time. Everybody wants her. She told me: “When I need to escape, I get on a plane and fly to Chicago. It is my secret city. I go where I want, do what I want, nobody recognizes me, nobody can find me.”

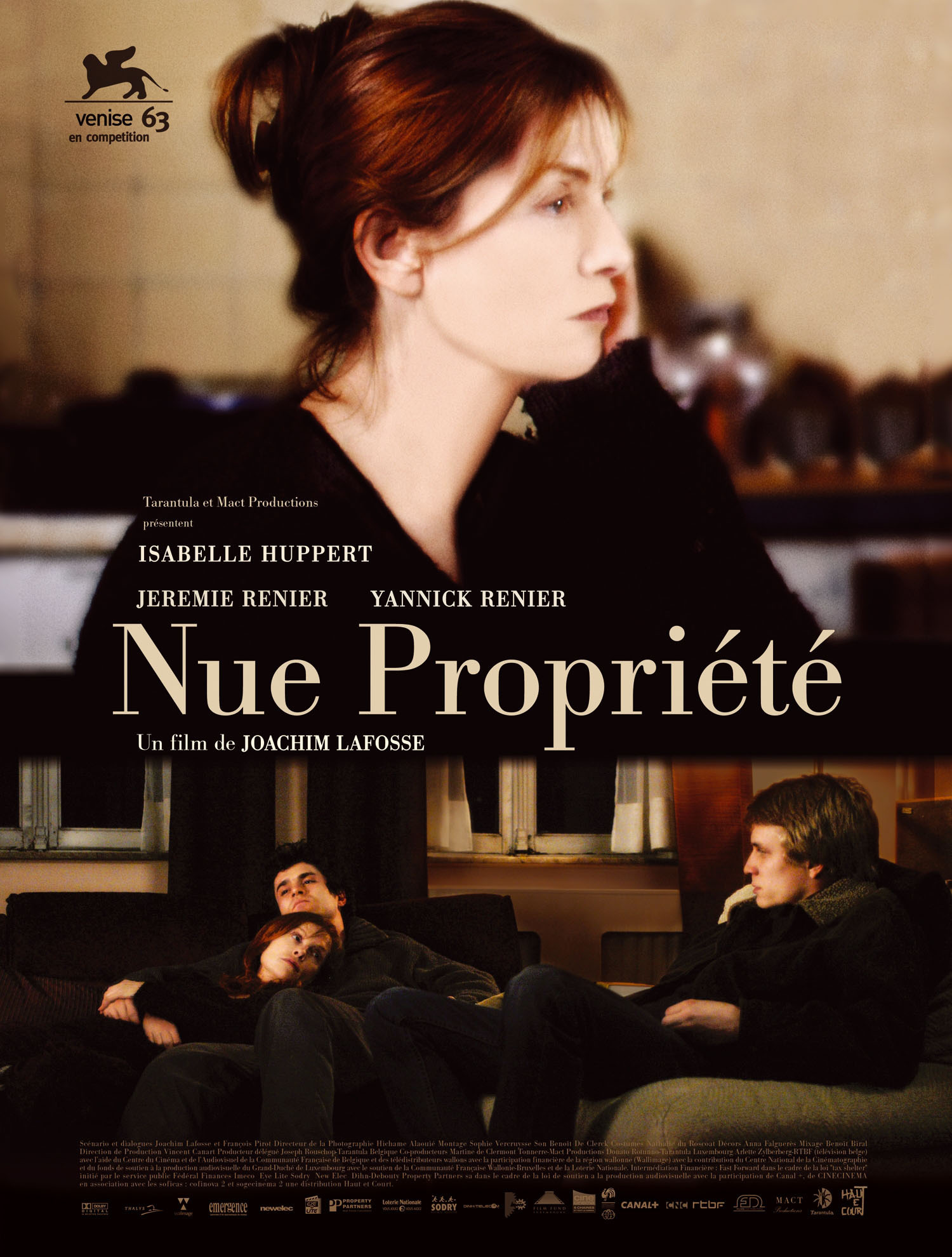

Now here she is in Joachim Lafosse’s “Private Property.” She plays the divorced mother of twin sons, who treat her badly, which she allows. They live in a big country house outside a Belgian town, bought for them by her ex-husband when he left. The husband has remarried and has a child. She has started to date a man, and they talk about running a B&B somewhere. It is time for her to live her own life. Her sons don’t think so.

They are Francois and Thierry, played by Yannick and Jeremie Renier, real-life brothers but not twins. Francois does odd jobs around the house and postpones his future, Thierry goes to school, the boys play games, they laze about, they are waited on hand and foot by their mother. Why should they leave? They have it good. They hate the new boyfriend, and that their mother is dating.

The film opens with Huppert, as Pascale, stripping and looking at herself intently in a mirror. Only Huppert could do this in quite the way she does; she is not presenting her nudity for examination, she is presenting her examination itself. One of the boys is watching her. If she realizes that (I think she does) it is a matter of indifference, and again later when she showers while another son is in the bathroom.

I don’t think this is intended to signal incestuous feelings. I think it signals that too many barriers have fallen between them, and she cannot reconstruct the walls that all parents need to put up sometimes.

The architect Christopher Alexander believes every house that has enough room should have a “couple’s domain,” an area off-limits for the children. Good fences make good families. Meals, we assure ourselves, “are the one time the family can get together.” In this family, they work as war. Pascale cooks, sets the table, serves the meal, and then sits down to hostility from Thierry and silent, withdrawn embarrassment from Francois.

She wants to keep peace. She does it by suppressing her own feelings. She knows what she wants, her freedom, but she can’t take it. Will the boys still be there when they are 30? They’re stuck on Mom. We remember Huppert’s great performance in Michael Haneke’s “The Piano Teacher” (2001), which won her the best actress prize at Cannes (“unanimously,” the jury specified). She played a fortyish woman who was still living with her mother, sleeping in the same bed, masochistically mutilating herself, then taking retribution in the sadistic manipulation of young men she had studied carefully. Both films draw on some of the same compulsions and inhibitions.

What draws us into “Private Property” is how so many things happen under the surface, never commented upon. At any given moment, we cannot say for sure what the characters fully feel, since they often act at right angles to their emotions. Lafosse said at film festival interviews that he was not even sure if the film was primarily about the mother. Is she simply carried along on the tide of her family? Are they drifting out to sea?

The story’s ending is brought about by actions involving the house. I will not be more specific. But it is hard to see how those actions could provoke all that happens. Sometimes the pressure in a family builds so that something relatively inconsequential pulls everything apart. We are accustomed to films in which the characters have fairly specific motivations. Huppert is inspired in the way she withdraws from confrontations and expresses her wishes enough to provoke others but never enough to realize them. An emotional balancing act showing such weakness takes a strong actress to pull it off.