First, a brief preface. Every time I review a film by Jean-Luc Godard, I receive outraged letters from readers who hated it. It is suggested that my reviews and myself join Godard on the trash heap of history; that the customers wuz robbed. A common complaint is that Godard “made no sense.” And so on.

So let this be a warning: You probably won’t like “Pierrot le Fou.” One of Godard’s films, seen by itself, can be a frustrating and puzzling experience. But when you begin to get into his universe, when you’ve seen a lot of Godard, you find yourself liking him more and more. One day something clicks, and Godard comes together. And then, perhaps, you decide that if he is not the greatest living director he is certainly the most audacious, the most experimental, the one who understands best how movies work.

“Pierrot Le Fou” marked the beginning of Godard’s current period. Before it came the black-and-white films — cool, quick and austere, with an emphasis on interpersonal relationships. After it came the Godard of color, wide screen and an increasing preoccupation with politics, American culture, violence, Vietnam and movies. (All of Godard’s films since “Pierrot le Fou” have essentially been movies about themselves — a statement hard to explain unless you’ve seen them).

“Pierrot le Fou” was made in 1966 but only released in the United States this year [1969]. Thus it comes to Chicago after “Weekend” (1968), a film it superficially resembles. Both films are about a man and a woman on a cross-country odyssey. The form is convenient because literally anything can happen. (When the couple in “Weekend” entered that forest, they even met Emily Bronte.) But “Pierrot le Fou” is more relaxed, more fun, less bitter than “Weekend.” And it contains Godard’s most virtuoso display of his mastery of Hollywood genres.

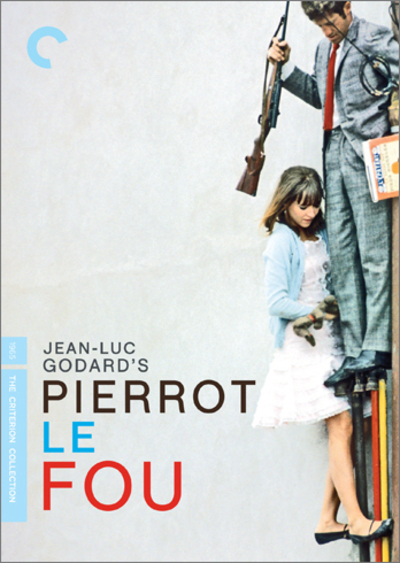

It seems to be a gangster picture: Jean-Paul Belmondo leaves his wife and goes to live with his former girlfriend, Anna Karina. She has apparently killed a man. They go on the lam in a stolen car, wind up on a deserted island, play the Robinson Crusoe bit for awhile, and then go back to the mainland to face the music (as Edward G. Robinson might have put it).

But Godard never sticks closely enough to this plot to make it important. He does a curious thing. He will have a scene that is perfectly conventional, like a scene in a Hollywood gangster movie. But it doesn’t come out of anything or lead into anything; it is important because of its tone, its texture and not because it advances the plot. Thus a Godard movie becomes a montage of pure technique; the parts don’t fit together — but they add up to an attitude. Does this make sense? More than any other director, Godard resists being written about.

But let me try an example. Belmondo wakes up in Anna Karina’s apartment. She is in the kitchen. He is in bed, smoking (a reference, if you will, to “Breathless” (1960)). The camera follows her into the bedroom and back to the kitchen. She sings a song to him. A piano supplies a modest background. It is one of the most charming musical scenes in recent movies. She continues to sing, and goes back to the kitchen.

In passing, the camera notes a dead body. It is just there. Nothing is made of it, but its presence changes the tone of the scene. Godard goes into a series of three close-ups: of her, of him, of her again. These shots cannot quite be described, but watch the movement of the actors’ eyes. Instead of moving his camera, Godard moves Belmondo’s eyes so that we “see” Karina moving. And we know she is going past the body again. This is an extraordinarily complex, effective scene: Not that it means anything, but that it is something. It is a feeling, a mood.

There are other such moments. At a party for advertising people, everyone talks like people talk in ads. But there is one misfit, an American film director (the auteur hero Samuel Fuller playing himself). He talks about being in Paris to make an action movie. His presence and language, and the movie he plans to make, seem infinitely more “real” than the artificial party. He is shot in full color; the others in tinted monotone.

As Belmondo and Karina march across France, they also march through movie history. At a gas station, they steal a car. It is necessary to deal with the gas station attendant. “Wait,” says Karina, “I know a trick from Laurel and Hardy.” She points up. The attendant looks up. She hits him in the stomach. Why not?

But all you can do, in writing about Godard, is to describe such scenes. And they don’t travel well. Godard, a former film critic, once said that the only valid way to criticize a movie was to make one of your own. That is true of his own work, at least.