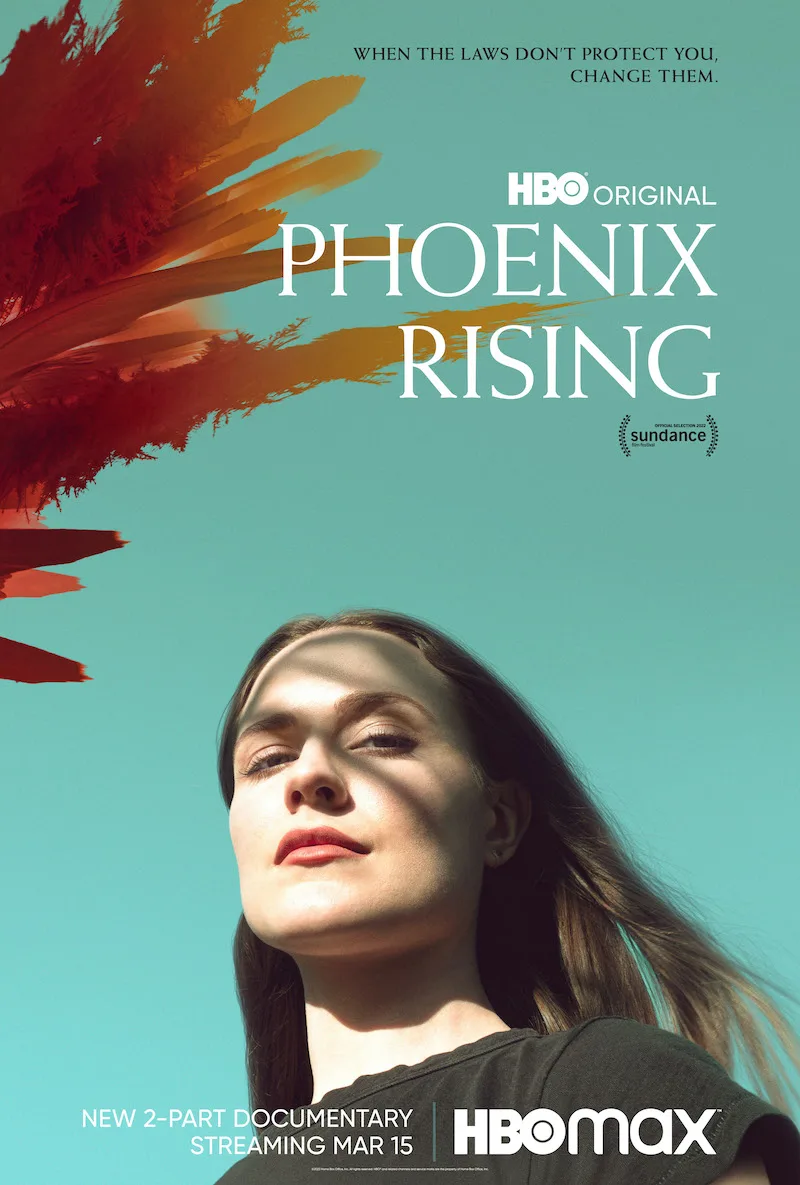

Even if you weren’t paying close attention to cultural gossip in 2007, the uproar about Marilyn Manson’s “Heart-Shaped Glasses” video—starring his 20-year-old girlfriend, actress Evan Rachel Wood—probably reached your ears. Manson was always criticized for taking things too far, but “Heart-Shaped Glasses” was another level. “Heart-Shaped Glasses” was a turning point for Wood, who had first made a splash with her performance in 2003’s “Thirteen,” and got labeled as a “troubled teen.” After the “Heart-Shaped Glasses” video, she was “trouble,” period. Over the years, as gossip blogger Perez Hilton has occasionally tried to re-brand himself as a kinder warm-fuzzier version, it’s impossible to forget that he nicknamed the actress “Evan Rachel Whore,” and would scribble the word “HO” over her face. She was 18, 19 years old. This was the kind of “press” Wood got, and it created an energy around her, one she was helpless to combat, particularly since she was trapped in an abusive relationship with Manson at the time. In 2021, Wood decided to go public with her abuse allegations and Amy Berg’s two-part documentary “Phoenix Rising” details that process.

“Phoenix Rising” opens in 2020, with Wood poring over her 2007 journals, reading sections aloud to her friend Illma Gore (introduced as “activist”). Wood met Manson (referred to as “Brian Warner,” his original name, throughout) at the Chateau Marmont in 2005. Wood was 18 years old, he was 36. Manson had seen “Thirteen,” and wanted to collaborate on a project about Lewis Carroll called “Phantasmagoria.” Manson was then married to burlesque artist Dita von Teese. The “friendship” with Wood segued into a relationship (and probably brought about an end to his marriage). The Manson-Wood relationship was tabloid-fodder (as his relationships always were), and “Heart-Shaped Glasses” fanned the flames. Wood continued to work in interesting projects (“Across the Universe,” “The Wrestler“), but behind the scenes things were spiraling out of control. She went on tour with Manson. He was, according to her, cruel, controlling, abusive. It took her a couple of attempts to finally extricate herself, helped by the intervention of family and friends.

Manson has denied all of Wood’s allegations, and just filed a lawsuit against her, where he makes some pretty damning accusations of his own. Other women have come forward telling very similar stories to Wood’s, and there is an emotional scene in “Phoenix Rising” when the survivors get together to swap notes. Alongside all of this, Wood reminisces about her childhood, and what it was like to be a young teenage actress in Hollywood (newsflash: it isn’t pretty). There’s a very brief section showing her recent attempts to extend the statute of limitations for domestic abuse allegations to 10 years, in a bill called the Phoenix Act. The leaping around in chronology is unnecessarily confusing, and the Phoenix Act battle—where she testifies before the California legislature, pleading the bill’s case to different representatives—is over in about 10 minutes, never to be mentioned again. The truncation of Wood’s very interesting years-long advocacy of the Phoenix Act is a baffling choice.

There are a couple of other missteps along the way, mainly the use of animation (and only in the first episode). Leaning heavily on the Alice in Wonderland theme, Wood’s story is illustrated as a wide-eyed young girl—looking to be about nine or ten years old—being sucked into a scary underworld, punctuated with pages showing the definitions for words like “grooming,” “love-bombing,” “isolation” in storybook-type fonts. The illustrations are so hallucinatory they take away from—as opposed to underline—the seriousness of Wood’s allegations, and the “loaded language” has a sameness to it which strips it of some of its power. There’s a scene where Wood defaces one of the watercolor portraits Manson did of her, and this too feels added on, heavy-handed, unnecessary. Wood’s trauma is undeniable. A more straightforward approach would have served “Phoenix Rising” well.

In the documentary “On the Record” (2020), former A&R executive Drew Dixon grapples with the difficult decision of whether or not to go public with her allegations against music mogul Russell Simmons. Filmmakers Amy Ziering and Kirby Dick stay close to Dixon throughout, and in so doing elegantly expose one of the larger themes so tragically common in these abuse stories: Dixon was run out of the business she not only loved but helped build. We all lose out when someone like Dixon no longer feels safe in her own industry. If a woman vanishes for seemingly no reason, there’s usually a story like this behind it. (See: Annabella Sciorra). As a fan of Evan Rachel Wood’s work since she first burst onto the scene in 2003, it has always been slightly confusing why she didn’t work more. She’s always so good! Well, now we know why. “Phoenix Rising” could have used some of “On the Record”‘s coolness and clarity.

Premieres on HBO on March 15th.