A love letter from one iconoclastic Italian Catholic artist to another, Abel Ferrara‘s “Pasolini” stays far from the cliches of the Hollywood biopic, embracing a fragmented, intense, impressionistic approach. Covering the last 24 hours in the life of its title character, this is one of the most intuitive and mysterious movie biographies made in a while. It deserves comparison to “Fruitvale Station” (which shares its Aristotelian unity of time and place, and likewise ends with a graphic, public murder) and “32 Short Films about Glenn Gould” (which tried to represent the artist’s work as well as key moments in his life). There’s not much rhyme or reason to where it goes at any given moment, and that’s a source of charm as well as frustration.

The subject is, of course, Pier Paolo Pasolini, the director of “The Gospel According to Matthew,” “Teorama,” “The Canterbury Tales,” “Arabian Nights,” and other art house classics. Pasolini, played by Willem Dafoe, was a public intellectual and artist, of a type that was more common in the mid-20th century than today. He was a novelist, an essayist and a philosopher as well as a writer and director of feature films.

But he was just as well known for the way he lived his life, and the way he articulated his views about Italian, Western, and global society—of the whole civilization, really. He was a Communist, an atheist, and a sharp critic of authoritarian government, capitalism, and the intersection of the two. He also lived a relatively open life as a gay man, which was rare for that time and place. He died at 53 in 1975, when he was beaten to death and run over on a beach, in a gay-bashing incident that some believe was also a targeted political killing. At the time of his murder, he had just completed his most notorious feature, “Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom,” based on the Marquis de Sade’s book.

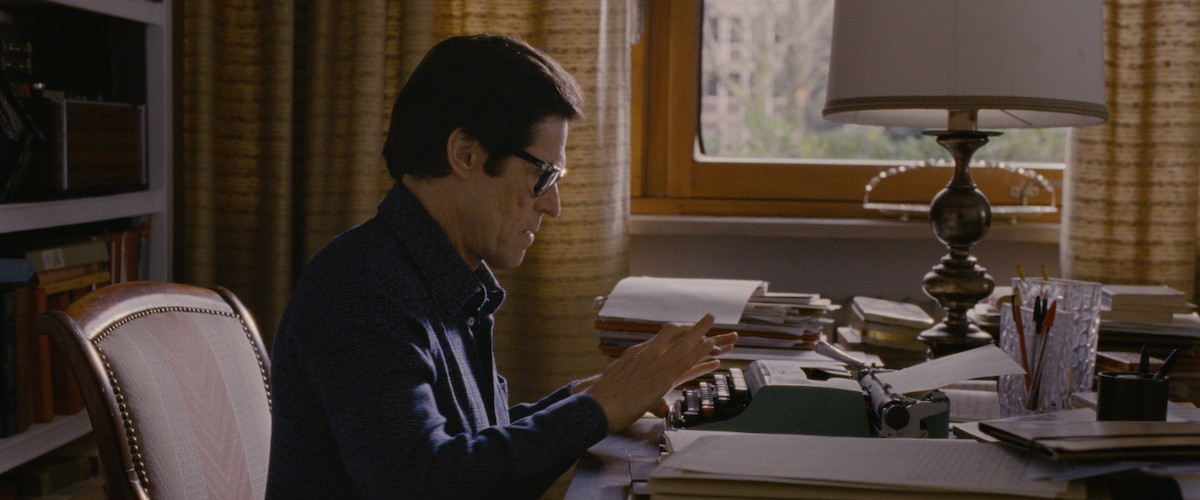

If someone were to ask “what happens” in this movie, the answer might sound like a put-on. We see Pasolini give interviews. We see him sketching storyboards, typing at a manual typewriter, and having dinner with his mother Susanna (Adriana Asti) and his friend Laura Betti (Maria de Medeiros), who played Emilia the servant in “Teorema” and would go on to direct a documentary about Pasolini’s life, 2001’s “Pier Paolo Pasolini e la ragione di un sogno.” There are two scenes of Pasolini driving in his Alfa Romeo late at night, cruising for young men, and a scene in a restaurant where he dotes on a baby. The re-creation of Pasolini’s death is one of the longest scenes, a kind of crucifixion, leaving Pasolini with no dignity, only agony and degradation. It’s cinema as violation, as difficult to watch as the brutality in a Pasolini film, or for that matter, Dafoe’s final moments in “The Last Temptation of Christ” and “Platoon” (he has died many martyr’s deaths onscreen, all stunning).

Sometimes the movie departs from simple observation and goes into Pasolini’s imagination, visualizing projects that he was working on before he died: a novel and a film. These interludes go on much longer than they would in a conventional biography, like thematically related short films shoehorned into a feature. The result sometimes feels like a kinder companion piece to Ferrara’s “Bad Lieutenant,” another movie about the final hours in a man’s life, though focusing on a very different, fictional (and menacing) character.

There isn’t much discernible logic to how the Italian language is presented. There are long, fully subtitled scenes in which Dafoe speaks Italian (not well) opposite native Italian speakers talking in their own language. There are scenes where Dafoe speaks unaccented English opposite Italian actors speaking English with Italian accents. In still other scenes, everyone is speaking Italian but the movie only subtitles the sentences that it thinks are important.

And yet, no matter how Dafoe’s performance is framed in terms of communication, he is convincing. You believe him as a man whose brilliance and appetites are so singular that there’s a limit to how emotionally close he can get to others. (Dafoe consistently nails this sort of part. Just recently he played Van Gogh in “At Eternity's Gate.”) There’s a mix of gentleness and defiance, serenity and disquiet to his work here that’s fascinating. It somehow suggests both the man Pasolini was and how people imagined that he was. The way Pasolini wears his glasses with those thick, black Guido-in-“8 1/2” frames; the delicate yet assured way he walks through a scene; the way Pasolini contemplates others and himself: all are the product of a discerning actor who has his director’s trust.

“Pasolini” is the sort of film about which a term like “successful” doesn’t seem to apply, because if you used it, the follow-up question would have to be, “Successful according to whose terms?” And the answer would be either “Abel Ferrara’s terms” or “Those of pretty much every other commercial filmmaker.” Then you’d be left with your own subjective response to the movie, which is something like walking across a ravine on a board that you won’t know is properly anchored until you stand on it. That this is a distinguishing feature of Pasolini’s filmography as well as Ferrara’s (along with an abiding interest in suffering, martyrdom, sensuality, and taboo) stands the project in good stead, no matter what you think of it as a complete work of art.

I found the movie somewhat unsatisfying as a whole, mainly because it takes a fair amount of time away from being in the presence of Pasolini and gives it over to visualizations of an unfinished novel and movie he was working on at the time of his murder, and these visualizations inevitably feel more like Abel Ferrara films inspired by Pasolini than coulda-been-Pasolini movies. To some extent, this was unavoidable, but the explicit sex in both sets of interludes is harder to rationalize. It feels like a straight filmmaker’s sincere but failed attempt to get into the mind of a gay artist.

At the same time, however, there’s no denying the singular spell that “Pasolini” weaves, by virtue of its stubborn determination to follow its own muse. The film was completed and premiered in 2014 and released to home video, but for various reasons hasn’t been given a theatrical release until now. It feels like a movie that would have been a big deal 25 years ago but must be content to be a curiosity now. Ferrara is a director proudly out of step with the times. He always was—Ferrara was a grotty, impassioned ’70s moviemaker at heart who found his groove in the early ’90s—but it’s even more true today. He’s a onetime drug addict turned Buddhist, legendarily difficult, volatile, and wild. He’s burned more bridges than General William Tecumseh Sherman. He doesn’t make television, tentpole films, or “content.” Even his work-for-hire (like “Body Snatchers” and the pilot of the old NBC series “Crime Story”) are inscribed with his distinctive signature, which is more like spray-painted graffiti than calligraphy. He makes self-contained, down-and-dirty yet intellectualized and philosophical, sometimes expressionistic, often short features, in a 20th century mode, in the spirit of some of the Italian auteurs he grew up admiring.

“Pasolini” is a vivid example. The point of this kind of movie is to spend time in the same room with, and sometimes inside the mind of, another person—practically meditating on them, or on the idea of them, and then going home and thinking about that person. “Pasolini” takes maximum advantage of the old-school approach, setting up scenes where we can just be with Pasolini, or with his thoughts, and ask us to linger there for a while, until the film is ready to move on to something else. There are five or six scenes in this film that send chills down my spine thinking about them. Almost all of them sound like nothing much of anything when you see them summarized on a page.

My favorite is the moment where Pasolini gives a long, eloquent statement to a reporter about the spiritual, political and economic condition of the world, then stands up and bids him farewell. The camera stays on Pasolini in closeup: on Dafoe’s weary, alert, deeply lined face. “I’ll Take You There” incongruously comes up on the soundtrack, and the camera stays fixed on Pasolini, refusing to cut away as he sinks onto the couch and turns slightly to one side.

Then comes a sequence of shots of Pasolini’s Alfa Romeo gliding through the streets of Rome at night, the director in search of an encounter—whether sexual or merely personal, we don’t yet know. The elapsed time from when that buoyant, flirtatious pop song comes on the soundtrack to when we see Pasolini behind the wheel of the car is nearly a minute, 1/84th the total running time of the movie.

It’s an eternity of nothing and everything. It’s a chance to just be.

This is what was taken from Pasolini. This is what will eventually be taken from all of us.