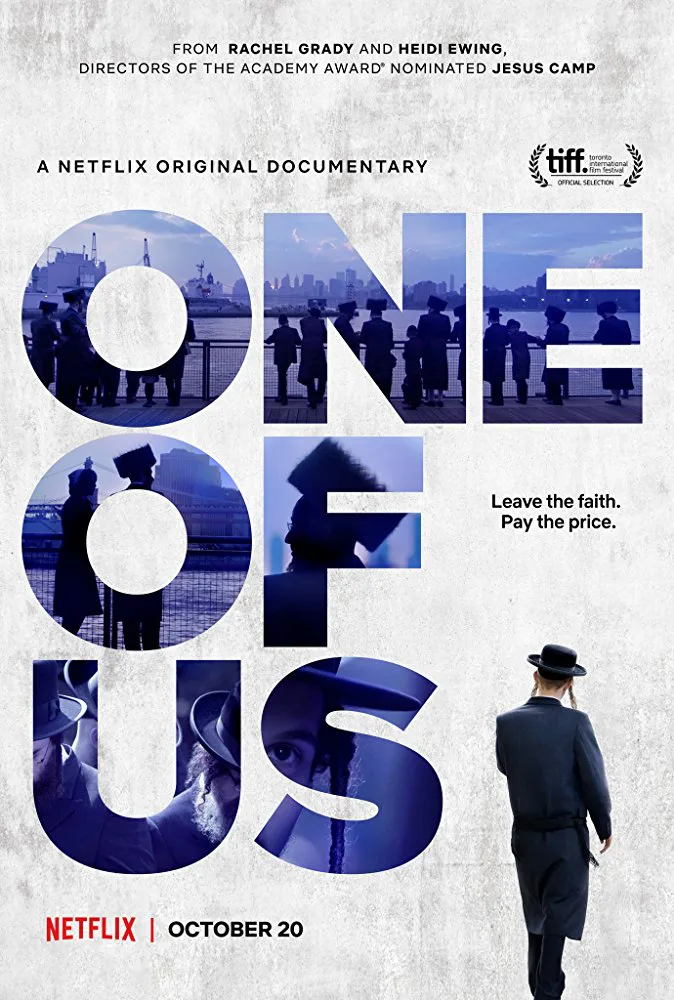

The title “One of Us” cuts deeply, in two directions. This documentary by Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady zeroes in on three individuals who were once part of a tightly knit community of Hasidic Jews in Brooklyn, New York. All three eventually left the tribe, as it were, because they found its conditions for membership suffocating, even abusive.

All three are caught by the filmmakers in the process of transforming themselves into secular Americans living life in the mainstream, enjoying the freedom that comes from being about to make bold personal choices, but also feeling abandoned and hated by the family and friends who remained on the other side. They’re becoming part of a larger world now—one of “them” as opposed to one of “us,” or maybe the other way around.

Teenaged Ari endured a horrendous crime as a child that was covered up by his community; it eventually contributed to his cocaine addiction (he’s survived two overdoses). Luzer is a twenty something man who realized one day that he couldn’t stand to live under the constraints of the community, got a divorce, left his family New York and moved to Los Angeles to pursue his dream of becoming an actor. Etty, now 32, has the most disturbing story. She was pushed into marriage with an abusive man at 19 and has had seven children. The entire extended family plus a wider circle of friends have joined forces to stop her from divorcing her husband and starting over.

This is complex and often explosive subject matter, and in examining it, the excellent team of Ewing and Grady (“The Boys of Baraka,” “Jesus Camp” and “Detropia“) tread as carefully as they can, given the constraints they’re under. Specifically, they can only tell one side of this story: the Hasidim, who rail against the secular world and are suspicious of cell phones and the Internet, aren’t about to sit for interviews with these filmmakers. That means that we’re never going to hear their side of things.

This is not to say that whatever we might might have heard would have created an “one the one hand, on the other hand” dynamic—clearly, all three of the filmmakers’ subjects had excellent reasons for leaving the community, and even if their reasons had been flighty or specious, they should still have had the right to determine their own destiny without fear of being ostracized or punished. That said, the most fascinating, albeit quite brief, portion of the movie comes in the form of a history lesson: we find out that the Hasidic Jewish community sprung up as a response to the Holocaust—that they see themselves as holy replacements for the millions who were slaughtered in the 1930s and ’40s. Everyone, including abusers, have reasons for doing what they do; a bit more on this subject might’ve made an already wrenching documentary even more powerful.

Then again, “One of Us” is so strong as-is that its more harrowing sections—particularly Ari’s account of his childhood suffering and the details of Etty’s fight for freedom—are so already hard to watch that you might want to turn away. There’s nothing more exhilarating or more terrifying than taking control of one’s own life.