Stanley Kramer‘s “Oklahoma Crude” is a tough, straightforward, well-acted movie about a male-female confrontation, and if it had been made 20 years ago that would have been enough of a description. In these enlightened days of women’s liberation, however, all sorts of additional messages have been read into the movie, and a lot of people seem to be reviewing notions that Kramer and his writer doubtless never had.

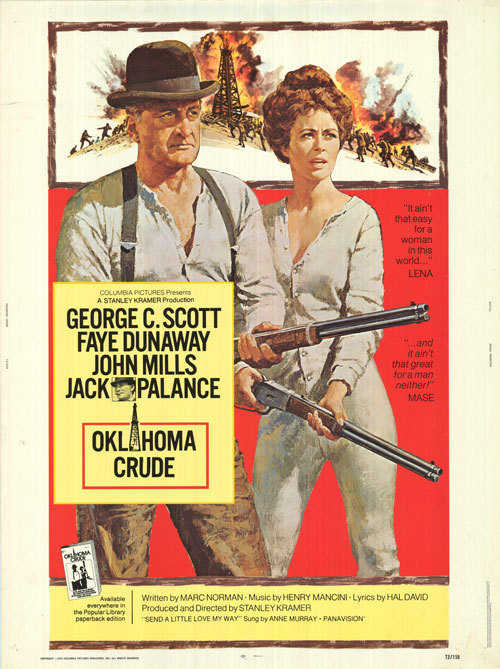

The movie’s female lead, played with a great deal of style by Faye Dunaway, is an independent soul who has staked her life and energies on an oil well. She wants nothing to do with men – not her father, and certainly not her father’s hired man (George C. Scott). But she does accept some help, reluctantly, and after a time a relationship of sorts develops between Scott and her.

We have seen this relationship many times in the movies, most memorably in “The African Queen.” The buried plot is always the same: Beautiful woman and uncultured man find themselves thrown together in a colorful enterprise. They have nothing in common except the enterprise, they think, but gradually their co-operation breeds respect, affection and finally love. Class barriers fall as the sun sets and romantic music swells.

This seems like a perfectly satisfactory scenario to me and has inspired some of the most interesting male-female relationships in movies. The shared task at least gets the couple out of the drawing room and into some adventure, and the woman is allowed to be competent and not some sort of fragile prize. Clark Gable had a relationship like that with Claudette Colbert in “Boom Town,” and of course most of the Spencer Tracy-Katharine Hepburn movies depended on it. But now at least some theorists of women’s lib believe Stanley Kramer, that most assiduous respecter of causes, has got it wrong. They don’t like the fact that Dunaway needs Scott, and especially they don’t like the fact that eventually she falls in love with him and gets all mushy (well, a little mushy) just like in all the stereotypes on the trash heap of sexism.

That’s missing the point, I think, and it’s also a little ironic. Kramer has built a career by developing movies around social themes. Here, for once, he wants only to entertain us-and his critics read a theme into the movie and attack him for it.

“Oklahoma Crude” deserves better. It’s set in 1913, in a new oil field, and it pits Faye Dunaway and her single lonely oil well against big tycoons and their hired goon (Jack Palance). That’s the story. We’re on her side, and we also hope she’ll finally see what a basically good person the Scott character is.

When she wins (and then loses, and then wins in a different way), we’re happy because we care for her. It spoils the frankly romantic ending if we get into the frenzy of feminism and start lashing out at love as a cop-out. And Kramer, to give him his due, has handled the ending on a restrained note that seems just right; we don’t get slow-motion shots of lovers running across a meadow (or an oil field) into each other’s arms.

George C. Scott just continues to grow as an actor; he’s been so good recently in so many different kinds of roles that I suspect we still don’t have his measure. This time he’s got to be strong but a little shy; a gentleman too proud to reveal his feelings – and sometimes scared to even feel them. His role is the pivotal one, in the way Bogart’s was in “The African Queen,” because in both cases the woman’s character has already been fully defined and it’s up to the man to demonstrate his worthiness.

Faye Dunaway, whose career has been rather absentminded since “Bonnie and Clyde,” hasn’t been better since. Perhaps she has decided to get back to acting and leave Marcello Mastroianni to Catherine Deneuve. I hope so.