The opening titles inform us that the Coen Brothers’ “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” is based on Homer’s The Odyssey . The Coens claimed their “Fargo” was based on a true story, but later confided it wasn’t; this time they confess they haven’t actually read The Odyssey . Still, they’ve absorbed the spirit. Like its inspiration, this movie is one darn thing after another.

The film is a Homeric journey through Mississippi during the Depression–or rather, through all of the images of that time and place that have been trickling down through pop culture ever since. There are even walk-ons for characters inspired by Babyface Nelson and the blues singer Robert Johnson, who speaks of a crossroads soul-selling rendezvous with the devil.

Bluegrass music is at the heart of the film, as it was of “Bonnie and Clyde,” and there are images of chain gangs, sharecropper cottages, cotton fields, populist politicians, river baptisms, hobos on freight trains, patent medicines, 25-watt radio stations and Klan rallies. The movie’s title is lifted from Preston Sturges’ 1941 comedy “Sullivan’s Travels” (it was the uplifting movie the hero wanted to make to redeem himself), and from Homer we get a Cyclops, sirens bathing on rocks, a hero named Ulysses, and his wife Penny, which is no doubt short for Penelope.

If these elements don’t exactly add up, maybe they’re not intended to. Homer’s epic grew out of the tales of many storytellers who went before; their episodes were timed and intended for a night’s recitation. Quite possibly no one before Homer saw the developing work as a whole. In the same spirit, “O Brother” contains sequences that are wonderful in themselves–lovely short films–but the movie never really shapes itself into a whole.

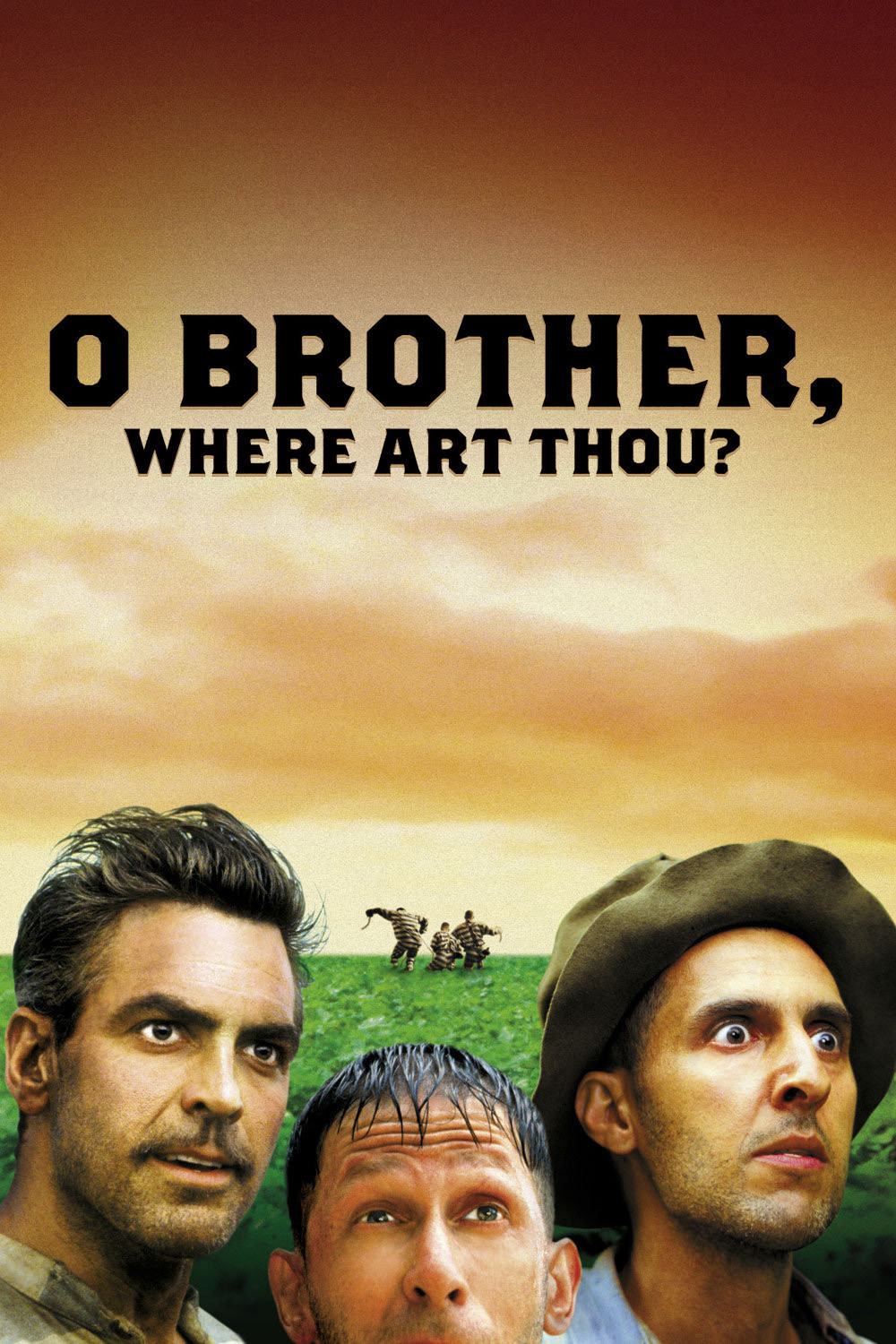

The opening shot shows three prisoners escaping from a chain gang. They are Ulysses Everett McGill (George Clooney), Pete (John Turturro) and Delmar (Tim Blake Nelson). From their peculiar conviction that they are invisible as they duck and run across an open field, we know the movie’s soul is in farce and satire, although it touches other notes, too–it’s an anthology of moods. McGill (played by Clooney as if Clark Gable were a patent medicine salesman) doesn’t much want company on his escape, but since he is chained to the other two, he has no choice. He enlists them in his cause by telling them of hidden treasure.

What was The Odyssey, after all, but a road movie? “O Brother” follows its three heroes on an odyssey during which they intersect with a political campaign, become radio stars by accident, stumble upon a Klan meeting and deal with McGill’s wife, Penny (Holly Hunter), who is about to pack up with their seven daughters and marry a man who won’t always be getting himself thrown into jail.

Hunter and Turturro are veterans of earlier Coen movies, and so is John Goodman, who plays a slick-talking Bible salesman. Charles Durning appears as a gubernatorial candidate with the populist jollity of Huey Long, and the story strands meet and separate as if the movie is happening mostly by chance and good luck–a nice feeling sometimes, although not one that inspires confidence that the narrative train has an engine.

The most effective sequence in the movie is the Klan rally (complete with a Klansman whose eye patch means he needs only one hole in his sheet). The choreography of the ceremony seems poised somewhere between Busby Berkeley and “Triumph of the Will,” and the Coens succeed in making it look ominous and ridiculous at the same time.

Another sequence almost stops the show, it’s so haunting in its self-contained way. It occurs when the escapees come across three women doing their laundry in a river. The Sirens, obviously. They sing “Didn’t Leave Nobody but the Baby” while moving in a slightly slowed motion, and the effect is–well, what it’s supposed to be, mesmerizing.

I also like the sequence of events beginning when the lads perform on the radio as the Soggy Mountain Boys. By now they have recruited a black partner, Tommy Johnson (Chris Thomas King), and later when the song becomes a hit, they’re called on to perform before an audience that is hostile to blacks in particular and escaped convicts in general. They wear false beards. Really false beards.

All of these scenes are wonderful in their different ways, and yet I left the movie uncertain and unsatisfied. I saw it a second time, admired the same parts, left with the same feeling. I do not demand that all movies have a story to pull us from beginning to end, and indeed one of the charms of “The Big Lebowski,” the Coens’ previous film, is how its stoned hero loses track of the thread of his own life. But with “O Brother, Where Are Thou?” I had the sense of invention set adrift; of a series of bright ideas wondering why they had all been invited to the same film.