“Norman Lear: Just Another Version of You” is a biography of one of TV’s most influential producers, and an influential American, period: the creator of “All in the Family,” “Maude,” “Good Times” and “The Jeffersons,” and the founder of the liberal activist group People for the American Way, which was founded as a response against evangelical activists to reclaim patriotism for the left. But while the film works as a primer for viewers who are curious about Lear but don’t know the details of his life and work, it’s more interesting as a movie about age and memory. Lear was 92 when the film was shot during a book tour last year, and while he’s as mentally and physically active as a person could hope to be at his age, the movie is suffused with melancholy, much of it stemming from Lear’s realization that most of his life is behind him.

Perhaps not coincidentally, it’s a film about faces. Most of Lear’s triumphs were in the 1970s: “All in the Family,” a politically-charged sitcom based on the English series “Till Death Us Do Part,” debuted in CBS in 1971, when the Vietnam War, the antiwar movement, and the feminist, gay rights and Civil Rights movements were still powerfully active. The movie is filled with shots of Lear on the sets of these shows, leading script readings and consulting with actors, looking fit and alert and slim, and always clad in his trademark fedora.

The documentary’s co-directors, Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady, shoot Lear in the present day with the sort of tender regard you might lavish on a grandparent if you had feature film-quality cameras and lighting and your grandparent didn’t mind being followed around by a movie crew. Their camera moves in close on Lear as he talks about his successes and controversies in American television, his collaborations with writers and actors, and his battles with network executives and censors over the political content of his shows, which resembled political debates as often as they did farcical family spats.

The moviemakers shoot some of Lear’s friends and collaborators, including “All in the Family” co-star and future feature director Rob Reiner and “Good Times” star John Amos, with just as much affection. All the images of deeply lined faces would be powerful on their own, but when they’re juxtaposed with shots of their younger selves—often being projected on a large screen while the older versions watch—the effect is magical: cinema as time machine. At various points they are all watching what amounts to the movie of their lives. The longest one is about Lear, who trips back through his own past with the filmmakers’ guidance, riffing on memories, telling stories, and tearing up at the sight of old friends who died a long time ago. The most touching sequences feature “All in the Family” star Carroll O’Connor, who played the bigoted working-class Irish-American Archie Bunker. Lear acknowledges that Archie is a version of his own father, and weeps while viewing the memorable episode where Archie describes his dad, a bigot who beat his values into his son, as a great man and a loving parent.

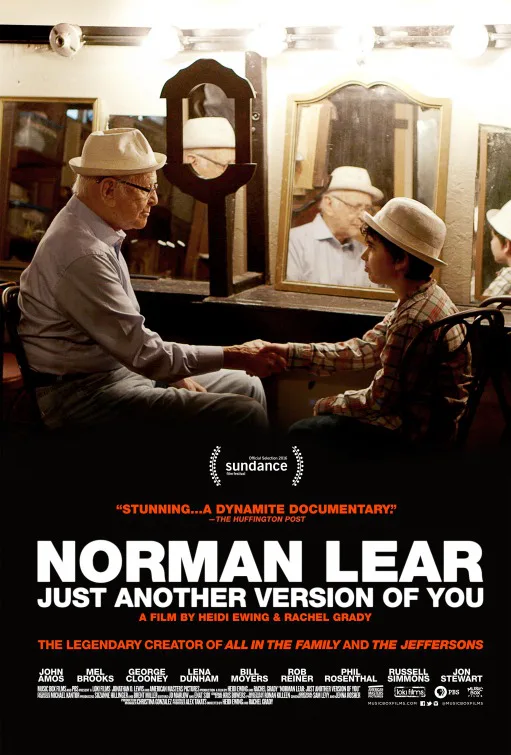

Jumping off from an early statement by Lear about how much he loves the magic of theater, the directors place him and the other present-day witnesses on a soundstage that suggests a set from an unproduced, off-Broadway multimedia drama. Interviewees are surrounded by significant life-props (including Lear’s trademark hat on a coat rack), hanging screens, movie lights and other theatrical and filmmaking paraphernalia, all clearly visible in the frame. The effect is reminiscent of the framing sequences in Bob Fosse’s “All that Jazz,” where the hero tried to seduce the Angel of Death while contemplating the arc of his life. There’s even a child version of Lear on hand, played by a young actor. This “Afterlife Café” set is the core of the film. The yellowed family photos, newspaper clippings and home movie and interview footage—stretching back through the 1960s and sometimes earlier—seem to radiate out from it.

The directors build out this Proustian notion by cutting from the present to the past without warning, as when Lear rides an elevated train through Upper Manhattan, glances out the window and sees train footage from that same train line when he was a boy. It’s all rather arty for what is ultimately a showbiz documentary about a famous TV producer, but while the time-machine technique doesn’t always feel necessary or right (sometimes you just want to hear people talking about what they saw and did and lose the other stuff) at least it’s a thoughtful attempt to give viewers an honest-to-goodness artistic portrait of Lear—an artistic representation of an artist, as opposed to a data dump that the audience could just as easily get by staying home and reading Wikipedia.

Unfortunately, these poetic effects often come at the expense of the basics. There are puzzling lapses in reporting: we learn, for example, that Lear’s vagabond con-man of a father went to jail when he was nine and that his absence devastated the boy, contributing to his lifelong distrust of father figures and authority, but we never learn what, exactly, the elder Lear was charged with, how long he was behind bars, or what eventually became of him. Later, Lear talks with agonized honesty about the collapse of his first marriage to Frances Lear, who was mentally ill; the anecdote ends with Lear searching her out after she disappeared and finding her on the floor of an apartment, but we never find out exactly what became of her.

These gaps and others are frustrating because they seem as if they could have filled without much trouble, and because the screen time they might have occupied is often filled up with scenes that feel like budget Fellini. The sequences dealing with the classic sitcoms are a bit frustrating, too, cutting away just when they seem to be building up a rhetorical head of steam; this is particularly noticeable in the “Good Times” and “The Jeffersons” sequences, which open up a can of worms related to race and representation that the film doesn’t quite know how to deal with.

Still, this is a striking piece of work. Lear is a great camera subject, a brilliant storyteller and so emotionally transparent that you might not mind if he went on for another half-hour—as long as it meant that you got to hear him talk some more, or watch him sit and think, or tear up over images of people who meant something to him.