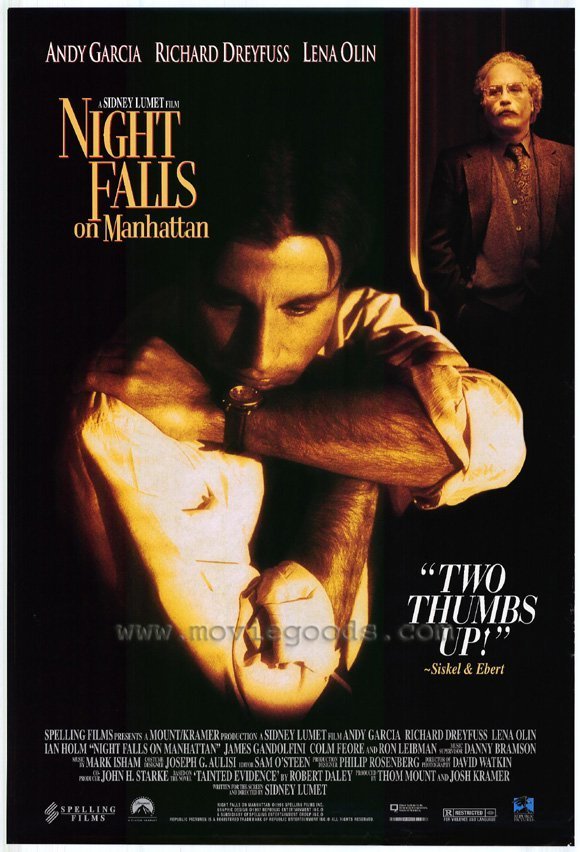

I see a slick, bemused man sitting behind a big desk in a dark room, flanked by his lieutenants. An evil man. I see a movie in which this sadistic puppet master devises diabolical schemes to destroy lives–until he is at last destroyed himself by the hero, in a series of chase scenes and shoot-outs.

This man I see has absolutely nothing to do with Sidney Lumet‘s “Night Falls on Manhattan.” Why do I begin with him? Because he is not in the movie. Because a clone of him is at the center of so many films about police and criminals, law and order. Because he is an example of creative bankruptcy–the stereotyped villain, who toys with a paperweight or a kitten, representing the inability of the filmmakers to find a good story in the world around them.

“Night Falls on Manhattan” is based on a book by Robert Daley, a New York writer who specializes in the shadowlands between right and wrong. It is about characters who have held onto what values they could while dealing in a flawed world. It has characters who do wrong and are therefore bad, but it doesn’t really have “villains” in the usual movie sense of the word. It’s too smart and grown up for such lazy categories–though it does fudge on the plausibility of a prosecutor being assigned to a case involving his own father.

As the film opens, a lawyer named Sean Casey (Andy Garcia) is being trained as an assistant district attorney. Those scenes are intercut with some cops on a stakeout: Casey’s father Liam (Ian Holm) and the father’s partner Joey Allegretto (James Gandolfini). They’re after the biggest drug dealer in Harlem. But when they try to burst through his door, a barrage of gunfire answers them, and Liam is critically wounded. The call for help is answered by three precincts, and ends in a fiasco: One cop is shot by another when a tire blowout is mistaken for gunfire, and the drug dealer ends up escaping in a squad car, while three cops are dead.

This creates a political hot potato for Morgenstern (Ron Leibman), the district attorney. His chief assistant Harrison (Colm Feore) expects to be assigned the case, but instead, for publicity reasons, Morgenstern gives it to young Sean Casey, the hero cop’s father. Leading the defense is hotshot Sam Vigoda (Richard Dreyfuss), who resembles Alan Dershowitz. One of the things Vigoda would like to reveal in court is why three precincts responded to the call when only one was supposed to: Were they turning up because they were all on the dealer’s payroll? Vigoda has a brilliant opening ploy: He produces his client (Shiek Mahmud-Bey) at a press conference and has him strip, so the reporters can be witnesses: “I am delivering my client in perfect condition. I want to be sure he turns up for trial in the same condition.” You see here how the complexities coil in upon themselves. The drug dealer is bad, yes, but are the cops heroes? Was the bust clean? Is there anything the young assistant D.A. doesn’t know about his father, or his father’s partner? There is a scene in a steam bath (where no one can wear a wire) between Casey and Vigoda, in which real motives and possibilities are gingerly explored. And as a result of the case, Casey finds himself sleeping with Peggy Lindstrom (Lena Olin), a lawyer in Vigoda’s office, who frankly tells him, “I knew I was seeing the start of a great career and I knew I couldn’t wait until I got you into bed.” Sidney Lumet is a director who is bored by routine genre filmmaking, in which everything is settled with a shoot-out. In such movies as “Dog Day Afternoon” (1975), “Prince of the City” (1981, also based on a Daley book), “The Verdict” (1982), “Running on Empty” (1988) and “Q and A” (1990), he shows how well he knows his way through moral mazes, where what is right and what is good may not coincide.

In this film he finds performances that suggest how tangled his characters are. Consider Leibman’s scene-stealing work as the district attorney: The character (not the actor) is sort of a ham, who enjoys pushing his personal style as far as it will go this side of parody. The way he speaks and moves fills all the volume of space around him. Is he a completely political animal? Not wholly. He has a very quiet, introspective latter scene in which he reveals a deep, sad understanding of his own world. It is a fine performance.

Consider, too, Gandolfini’s Allegreto, one of the cops on the original bust. What does he know that he isn’t telling? Young Sean has known his father’s partner for a long time. Can he trust him? “I swear to God, Sean,” the partner says, looking him straight in the eye, “your father is clean.” But can he even trust his father? When asked why only two cops were on such an important bust, the old man testifies significantly, “In narcotics you gotta be careful. On a good lead you don’t want too much word out.” “Night Falls on Manhattan” is absorbing precisely because we cannot guess who is telling the truth, or what morality some of the characters possess. In a lesser movie, we’d be cheering for the young assistant D.A. and against the slickster defense attorney. When the Lena Olin character climbs into bed with the hero, we’d suspect treachery or emotional blackmail. We’d assume the original cops were either heroes or louses. We’d assume that Harrison, the D.A.’s second in command, would be a schemer out to further his own career at any cost.

Here we don’t know. Here intelligence is required from the characters: They’re feeling their way. They’re been around. They know movie courtrooms aren’t like real ones, and that movies simplify life. They know that sometimes good people make mistakes, and that even those who break the law may be fundamentally committed to upholding it. That in a society where people find a choice between abject poverty and selling drugs, not everyone has the luxury of deciding in the abstract.

This movie is knowledgeable about the city and the people who make accommodations with it. It shows us how boring that obligatory evil kingpin is in so many other crime movies–sitting in his room, flanked by his henchmen, a signal that his film is on autopilot and we will not need to think.