Sidney Lumet’s “Q & A” is an excitingly well-crafted police movie, but he’s a good director and I think that was the easy part for him. What was hard–what the movie is really about–is the rough and careless way that cops and other tough guys throw around racial insults. I’m not talking about how they address their clients out in the streets, I’m talking about how they regard each other–the Blacks and Irish and Jews and Hispanics and Italians and Slavs who make up their world. It is almost a badge of honor in certain circles to use, and ignore, racist verbal labels.

What does that kind of talk signify? Is it said in affection? Sometimes. Sometimes not. Is it said as a territorial thing–I’m Italian and you’re not? Is it tribal, reminding everyone of loyalties that can be called on in times of trouble? At some level it’s accepted–everyone in this movie uses racial and ethnic slang constantly–and yet, at another level, it is just what it sounds like, a kind of macho name-calling?

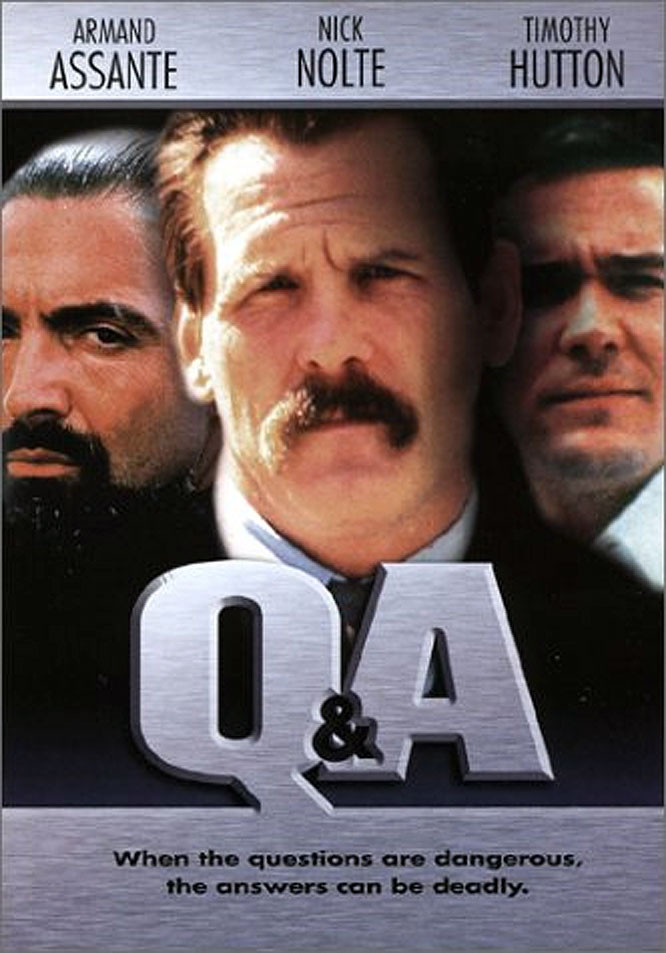

In Lumet’s New York City, the streets are seen as dangerously near to spinning out of control. To the Irish-American chief of the homicide bureau (Patrick O'Neal), that means it is time to close ranks. It’s a war out there, he believes, between the cops and the people who would destroy the city (by which he instinctively means Blacks and Hispanics). When a legendary Irish street cop named Brennan (Nick Nolte) shoots a Puerto Rican in a slum doorway, O’Neal calls in a young Assistant D.A. (Timothy Hutton) to head the investigation. But he briefs Hutton very specifically: “This is an open-and-shut case.”

It is not. Hutton begins to suspect that Brennan may have committed murder. His investigation leads him into the lives of people in many different ethnic groups–and he is shocked one day when a Hispanic drug dealer (Armand Assante) walks in with a woman (Jenny Lumet) who Hutton once dated, and still loves.

He meets her privately, and asks her to come back to him. She will not. He assumed she was Hispanic when they dated, and she will never forget the look in his eyes, she says, when he met her father for the first time, and learned that she was black. Is it always there, the movie wonders–that instinctive racial discrimination that seems to be absorbed when we’re young, and has to be unlearned as part of the process of growing up and growing better?

The movie is about such questions, but in a subtle way, while the central story involves a web of treachery, bribery and deceit. This is a movie with a large cast, and one of the ways Lumet deals with that is to use fine, experienced actors who almost exude the traits of their characters. There’s Charles Dutton, as a hard-boiled black detective who explains that his real color is blue–“and when I was in the Army, it was olive drab.” There’s Luis Guzman as his partner, a Puerto Rican detective who knows and accepts the realities of the streets but has his limits. There’s Lee Richardson as an old Jewish lawyer who has high standards and gives wise counsel to Hutton–but is also finally part of the system.

These people and others give us the sense that “Q & A” isn’t just about a hermetically-sealed plot; that its tendrils reach out into the whole hierarchy of law-enforcement in a city like New York, and that the patterns seen here in the 34th Precinct are repeated in every other precinct, and every other big American city. Nick Nolte’s performance is central to that feeling. He knew Hutton’s late father–a hero cop–and he also knows dirt on the father that he can use if he has to. It’s fascinating to see the way he works on this kid. He’s been screwing the system so long, he knows just what buttons to push.

One of the most interesting characters in the movie is Bobby Texador, the drug kingpin, played by Armand Assante in one of the best character performances of the year. I didn’t recognize Assante at first behind the beard and the silken, poetic speech, but what I did recognize was an original character–not simply your standard movie drug dealer, but a man whose skills and cleverness had led him to success in his business, and who was smart enough to want out (it’s the rare drug millionaire–or any millionaire–with the imagination to have as much fun spending money as making it).

Lumet has made a lot of other movies about tough big city types of one kind of another (“Dog Day Afternoon,” “Serpico,” “Network,” “Prince of the City,” “The Verdict“), but this is the one where he taps into the vibrating awareness of race which is almost always there, when strangers of different races encounter each other in situations where one has authority and another doesn’t. The law provides a context for how cops treat civilians, criminal or not; but does it also provide an arena where a racial contest for power in the city takes place? Can the law be color-blind, when none of its instruments are? It is fascinating the way this movie works so well as a police thriller on one level, while on other levels it probes feelings we may keep secret even from ourselves.