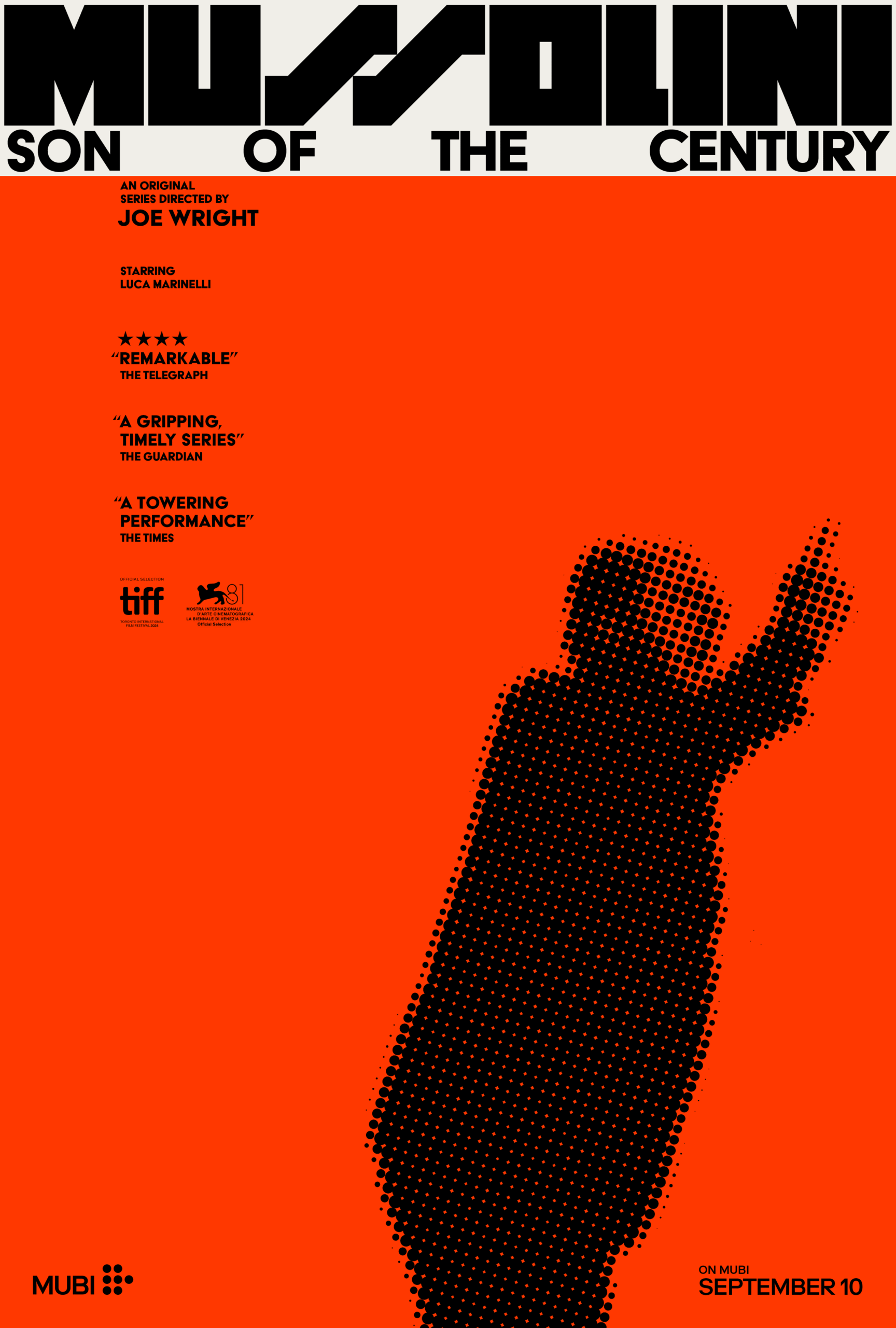

It can be easy, in the liberal enclaves in which so many of us live, to shake our heads at the incipient rise of fascism in the United States and across the world and ask ourselves, “How did we get here?” Joe Wright, the director of “Atonement” and “Pride & Prejudice,” wondered that too, and looked to the past to map out our present in the eight-part Sky One (and, in America, Mubi) series “Mussolini: Son of the Century.” But rather than paint it as some dry history lesson, Wright turns the show’s eight-hour chronicle of Benito Mussolini’s rise from leader of the Italian Fasces of Combat to fascist dictator into the kind of perverse bacchanal that makes you understand why leaders like he, venal as they are, might find purchase among the disenfranchised. “Follow me,” he leers into the camera. “You’ll become fascists too.”

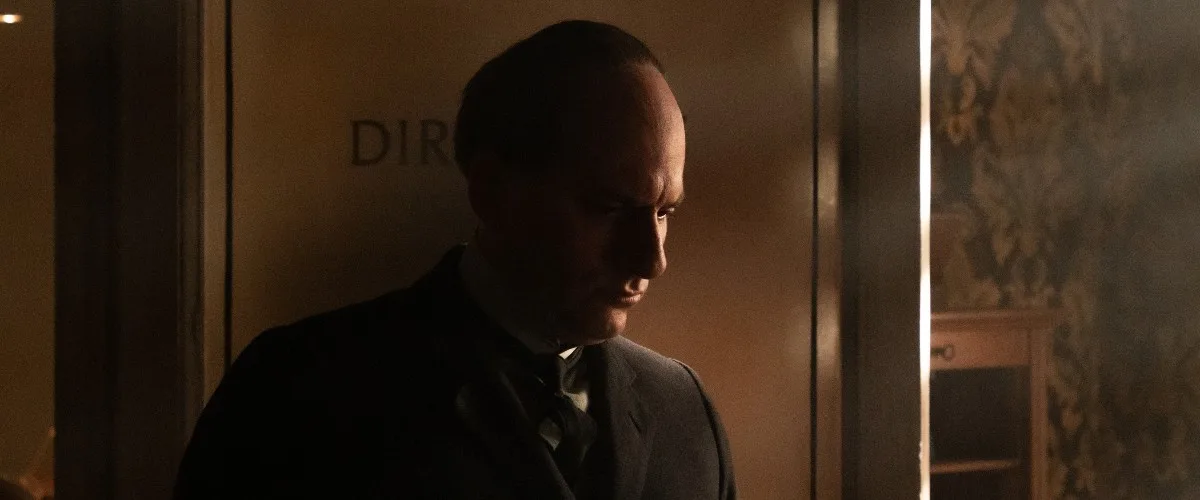

Those “House of Cards”-style addresses are front and center in Wright’s series, adapted from the first volume of Antonio Scurati’s award-winning book of the same name. From the get, Wright (and star Luca Marinelli, transforming himself from “Old Guard” heartthrob to corpulent political striver with remarkable seamlessness; he’s unrecognizable but unforgettable) brings the audience into Mussolini’s confidence, the man sneering and winking and confessing to us as if bragging about his plans.

When we first meet him, he tells us about the angry, broken, saluting men around him at a 1919 meeting of the Fasces of Combat—a group of men broken down by the Great War, injured and marginalized, desperate to beat up the socialists who’ve taken purchase at the highest levels of Italian government. “All it takes is the right words to get a populace to adore and worship you,” he explains.

“I’m like an animal. I can smell the times ahead. And this is my time.”

Over the next eight hours, we see his efforts to gain power in the Italian government, stymied by everything from the infighting among his fellow fascists, the unpopular actions of his Blackshirts, and the paranoid scheming of his quislings (including Francesco Russo’s porcine Cesare Rossi, whispering in Benito’s ear like Grima Wormtongue). Indeed, “Son of the Century” is content not to paint Mussolini as some grandmaster playing fourth-dimensional chess; he’s a blustering, self-doubting moron, who merely wants power for its own sake, and who monologues to an enormous metal bust of his head later in the series about the many, many ways his revolution can go wrong.

Even the women in his life carry a strange power over him, despite his chauvinism: Wife Rachele (Benedetta Cimatti) bites back at him as master of their house, and his muse and mistress Margherita Sarfatti (Barbara Chichiarelli) finds ways to humiliate him both in public and private. The movement itself deals with setback after setback from entrenched socialist powers, and Mussolini merely barrels his way through them with all the stubbornness of a mule.

But what intrigues most about the show is the way Wright documents this slow, staggered rise to power: there’s a buzzy excitement to the frenzied, frenetic editing, drawing from the Italian Futurists of the 1920s to pull out just about every trick in the experimental filmmaking book. There are nods to Dziga Vertov and “Man With a Movie Camera,” Howard Hawks’ “Scarface,” and more; Wright shoots dialogue (and Marinelli’s numerous asides to camera) with disorienting Dutch angles, low-angled closeups, and all manner of unconventional frames. Tom Rowlands, one half of the Chemical Brothers, scores the whole thing with a driving, pulsing techno-synth beat that makes this feel like it’s taking place in 2220, not 1920.

Grenades spin, cross-cut with spinning ballot bins, and the pressure cooker Mussolini endures grinds alongside closeups of pencil sharpeners. The locations, whether interior or exterior, feel like sets; car windows consciously show rear-projection of crowds and streets. It’s all very presentational and Brechtian, and the nonstop pace leaves you breathless.

Sometimes that frenzy works against “Son of the Century”; Wright is so concerned with keeping us swept up in the rising tide of fascism—the parties, the sex, the politics—that it begins to grow repetitive and one-note the longer the series goes. There’s no respite from the vulgarity on display, whether it’s the staccato thrusting of Mussolini in one of many lovers (including a POV shot where we get to see a discomfiting closeup of the dictator’s vinegar strokes) or the march-march-march of fascist feet as they walk around a circle so Mussolini’s speech can turn into a kind of techno-rap soliloquy. It’s all so very mucmh, and unless you’re accustomed to the relentless rhythms of, say, Baz Luhrmann, “Son of the Century” can often leave you adrift when it forgets to play it straight.

But perhaps that’s the point; 1920s Italy is a gonzo land of lost citizens and political upheaval, with all the players involved either ideologically or literally (see Prime Minister Nutti, sat diminutively in a high-chaired throne with his jackbooted feet dangling) hobbled. And none more so than Mussolini himself, a man who shouts and gestures and only calls for violence to end when he feels it would compromise fascism’s image. Fascism succeeds by overwhelming us, by stunning the senses with one transgression after another, coming so fast that sensible, gentle, good-hearted people can’t possibly react to all of them. It’s a point Wright is demonstratively pointing to while we live in our current political moment (At one point, Mussolini turns to the camera, beaming, and barks, “Make Italy Great Again!”).

It’s all flashy, and unsubtle, and more than a little labored. But for those looking for a glimpse into the psychic whirlwind that can hurl a people, and a nation, into tyranny, “Mussolini: Son of the Century” is a sobering but exhilarating watch.

Full series screened for review. Currently streaming on Mubi.