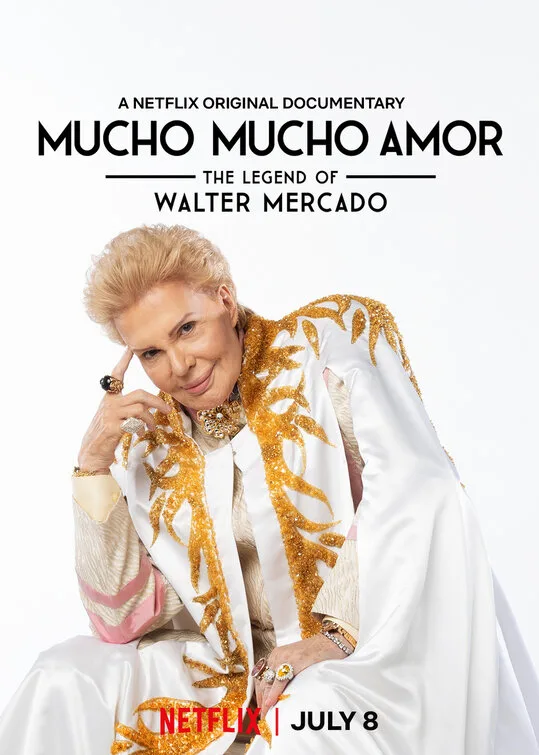

Every culture has a list of its own idiosyncratic TV personas weaved into its fabric. Though it’s safe to assume that few can be as fiercely one-of-a-kind as Walter Mercado, the larger-than-life, gender-nonconforming Puerto Rican-born astrologer who allured millions of viewers across the United States, Latin America and even Europe for decades, spreading his intoxicating optimism while wrapped in extravagant jewels and flashy capes. In “Mucho Mucho Amor: The Legend of Walter Mercado” (the first part of the title doubles as the heartwarming closing phrase Mercado used at the end of his hour-long TV programs), documentary filmmakers Cristina Costantini (“Science Fair”) and Kareem Tabsch (“The Last Resort”) celebrate and eulogize the late showman with disarming zest and respect, unpacking how he and his horoscopes became staples of the Latin culture over the years.

If you, like me, are new to Mercado’s opulent world of positivity, mysticism, and blindingly shiny trinkets, have no worries—the directors are so openly enamored by it all that by the end, you might just profess yourself a brand-new fan of this awe-inspiring figure. But if Mercado has been a part of your family life and upbringing in living rooms where people used to practice radio-silence to hear his wisdom and musings—as is the case for an enthusiastic Lin-Manuel Miranda, among the film’s most famous talking-head interviewees—the generously hagiographic “Mucho Mucho Amor” is likely to cast a nostalgic spell on you.

But before the film gets there, Costantini and Tabsch kick things off on a curious note. Following a glorious montage of some of Mercado’s signature charms and appearances as an Oprah or Mr. Rogers-like presence who broke down barriers between generations, “Mucho Mucho Amor” informs the viewers that he disappeared from the public eye in 2006, after decades of abundant fame that started in 1969. But the film quickly alters its course and steers away from an investigative, “Searching For Sugar Man”-like destination that it hints at. Instead, we soon find ourselves in the company of the captivating Mercado, in his heavily propped and charmingly cluttered home resembling a majestic and well-kept version of Grey Gardens, ready and willing to tell his own story as a man who was once asked by Howard Stern whether he’s bigger than Jesus Christ. Accompanying him is his ever-devoted assistant Willie Acosta, who defines himself as not only Mercado’s right hand, but his left one, too.

Under the guidance of Costantini and Tabsch, Mercado takes us to his early beginnings in Puerto Rico as a boy who was always destined to be atypical. Often picked on for his feminine mannerisms in a culture where homophobia and antiquated ideas of masculinity were looming large, the young outcast was encouraged by his mother to embrace his uniqueness as a gift. And that’s when his saga began in earnest, with Mercado appointing himself to become a child healer of sorts. Cuddling the theatrics of this invented personality even closer in later years, Mercado poured his creativity and craft into a mélange of spirituality and clairvoyance, giving affirmative blanket advice to all astrological signs that made him a hit and a must-see, especially among optimism-seeking immigrant populations. Along the way, his sexuality always remained a question mark as he never came forward with a declaration. Still, the unapologetically fluid Mercado was a pioneer in LGBTQ representation in entertainment and shook up notions of manliness even when the culture that surrounded him remained cruelly intolerant of homosexuality.

The filmmakers structure all these moving parts tidily, and blend interviews, reenactments, and archival footage into segments defined by animated tarot cards. Also a part of the assembly is an exhibition organized by a museum in Miami to celebrate Mercado’s legacy in the Latino culture. There are also various disputes with Bill Bakula, Mercado’s exploitative ex-manager who built his client’s name and brand, but later on, tried to take ownership of them, causing Mercado to disappear from the public eye. The resulting brew is both widespread and a touch overlong, but never without a sense of lush melancholy, exemplified best when Miranda finally meets his personal hero who paved the way to so much for Latinx communities.

While Mercado passed away just last November, it wasn’t before he was able to complete the interviews for the film and attend the museum show in his honor—two pieces of profound farewells to an incomparable personality, who was surrounded by friends and family in his final moments. It was the kind of dignified exit he so richly deserved.