Within the first 10 minutes of Joss Whedon‘s “Much Ado About Nothing,” I found myself smiling with excitement, while also holding my breath in nervous anxiety. Would the film be able to sustain its confident manic tone, maintain its humor and smarts, its depth of characterization and innovative use of text and landscape? Would the magic hold? The magic holds. It holds from beginning to end.

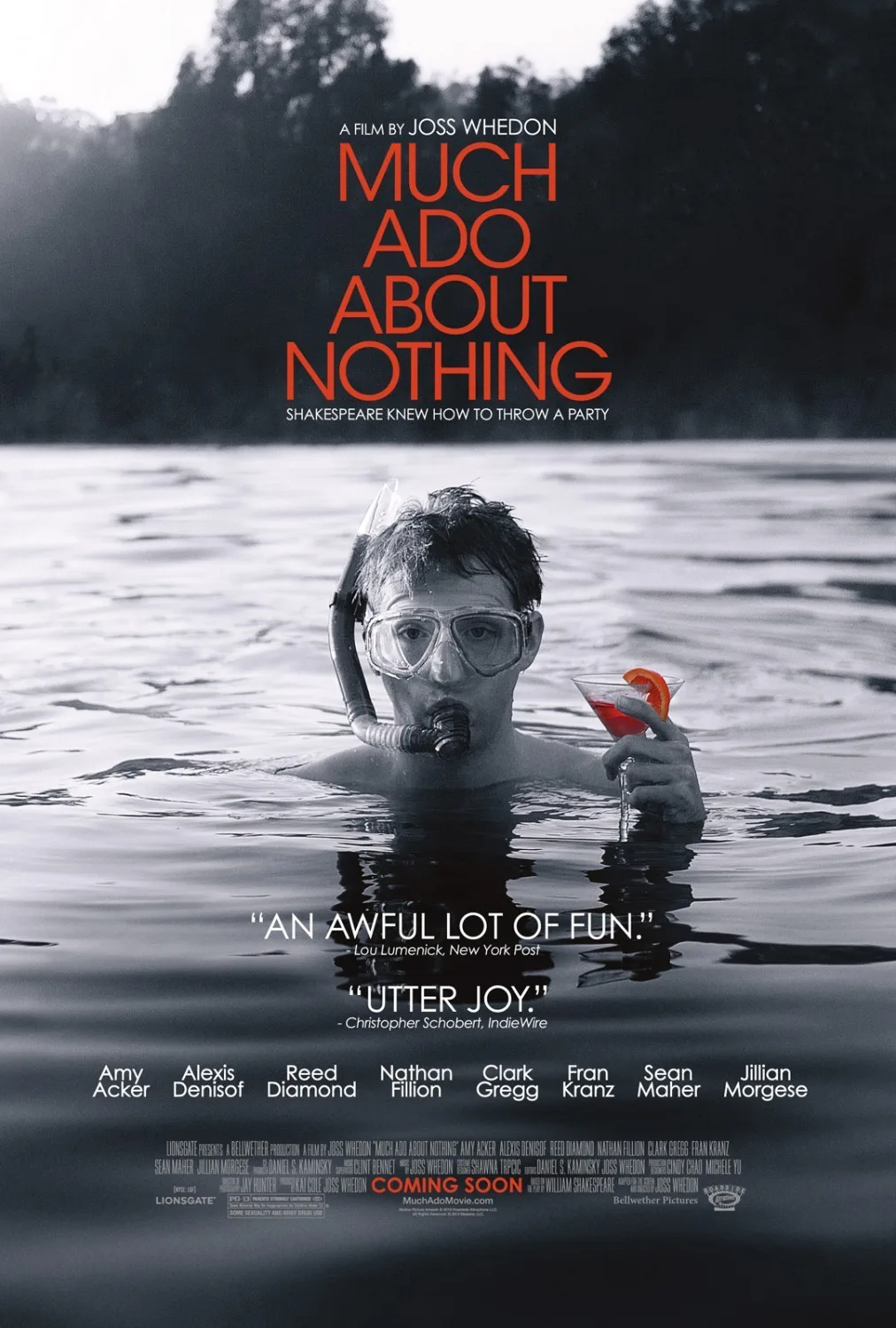

Audiences will remember Kenneth Branagh’s well-received version from 1993, with the cast of stars tumbling and laughing over bright hillsides in Tuscany, dressed in flowing period garb. Whedon takes a different approach. It’s done in modern dress. There are no big stars in it, although fans of Whedon’s films and television series will recognize many of his regulars. He shot in glamorous black-and-white (Jay Hunter was the cinematographer), which may seem like a serious choice for such comedic material until you remember that some of the funniest comedies ever made were filmed in black-and-white. Whedon firmly places “Much Ado About Nothing” in the screwball tradition where it belongs. He uses one main location (his own house), and much of it takes place in echoing high-end interiors, perfect for a story where everyone is constantly eavesdropping on everyone else. The acoustics in the house are very poor for anyone who wants to keep a secret. The adaptation, done by Whedon, is terrific. The play moves from comedy to tragedy and back with dizzying speed, and while you may feel like you’re getting whiplash, that’s the desired effect.

Whedon, beloved by television audiences for his cult favorites “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and “Firefly” (to mention just a few), is known for creating independent and memorable female characters, and in this, Shakespeare is a perfect fit for him as a director. Shakespeare created Rosalind in “As You Like It,” Katherine in “Taming of the Shrew,” Lady Macbeth in “Macbeth,” Cleopatra in “Antony and Cleopatra” and a host of iconic others. Misogyny is alive and well in Shakespeare and takes on a particularly vicious aspect in “Much Ado About Nothing,” when a woman’s virginity is prized above her humanity, but Shakespeare, as usual, has his cake and eats it too. “Much Ado” strolls into some pretty dark forests, morally and spiritually, and while I’m not sure that Hero, the betrayed heroine, would agree with the title that it all had been “much ado about nothing,” the crookedness of the universe is righted gloriously in the end.

The intrigues of Italian war and political life are merely backdrop in Shakespeare’s comedy and it’s backdrop here, too. The opening shows Don Pedro and Claudio (Reed Diamond and Fran Kranz, both excellent) returning from abroad, complete with security detail and a motorcade of gleaming cars. They bring with them Benedick (the marvelous Alexis Denisof), Don John (Sean Maher, who looks like Robert Chambers, the Preppy Murderer, a perfect choice considering Don John’s malevolent character), and Don John’s cunning sidekick Conrade (played, in Whedon’s version, by a woman, Riki Lindhome). They stop off at the beautiful home of Leonato (Clark Gregg), to celebrate with relatives and friends, all of whom have nothing else to do besides hang out in the house, drink wine, gossip, and make mischief with one another’s love lives. Claudio confesses to Don Pedro that he has fallen in instant-love with Leonato’s beautiful young daughter Hero (Jillian Morgese). Don Pedro immediately begins scheming on a way to bring the romance to fruition. A masked ball thrown that night gives him the opportunity he is looking for.

Hero’s cousin Beatrice (played by Amy Acker) tells anyone who will listen (and even those who tune her out) that love is not for her, and marriage is for the birds. She especially wants everyone to know that Benedick is a jerk, and he doesn’t matter to her at all! Benedick returns her insults, to her face and behind her back. Of course if the two were as indifferent towards one another as they declared, then why do they keep talking incessantly about each other? Hero and her maids, along with the menfolk in the house, conspire to bring the arguing two together.

All of this love-making could have gone forward without a hitch if Don John had not been in the house. Don John is disturbed by other people’s happiness. He is the evil version of the melancholy Jaques in “As You Like It”. He has no purpose beyond making trouble for others. He figures out a way to make it seem as if Hero had been unfaithful to Claudio, on the night before the two were to be wed. Claudio reacts ferociously. Hero faints. Leonato screams that his daughter has besmirched his family name. Don John smiles happily. Beatrice and Benedick find themselves unlikely allies in untangling the web of intrigue and malice.

Doug Moston, acting teacher and Shakespeare scholar, had this to say to his classes about Shakespeare’s language: “If you think a line is bawdy, it’s bawdy. If you don’t think it’s bawdy — it’s only because you haven’t worked it out yet.” Joss Whedon and his capable cast have “worked it out.” Every line shimmers with double entendre. Sex roils underneath every moment, every motivation, every misunderstanding and every rejoinder. Even the scene between Don John and Conrade, where Don John discusses how disturbed he is by joy, becomes a scene of hot foreplay between the two, where lines like, “If I had my mouth I would bite; if I had my liberty, I would do my liking” take on new worlds of meaning.

Dogberry, a policeman in charge of security at Leonato’s house, enters the scene late in the game, having stumbled across the plot against Hero, and once he arrives you never want him to leave. Dogberry tries to sound smart and official, all while saying things like, “You shall comprehend all vagrom men,” when he clearly means “apprehend” and “vagrant,” or dispatching his security guards with the order, “Be vigitant, I beseech you.” He is ridiculous, saying these mispronounced words with total confidence. He covers up his incompetence and lack of vocabulary with a bluff swaggering persona, complete with dark sunglasses, and Nathan Fillion, from “Firefly” and “Serenity,” gives a great and entertaining comedic performance.

Beatrice and Benedick steal the show, though, in this version and in every version I’ve seen, on film or on stage. Nobody has informed the two of them that they are not the leads, that their romance is the subplot. Their barbs are sometimes vicious, and both characters show a studied indifference towards marriage and love. Beatrice and Benedick are the patron saints of 1930s screwball comedy. Sam and Diane from “Cheers” carried on their tradition. Any rom-com we see today is haunted by the arguing defensive love-mad ghosts of Beatrice and Benedick. The two are so equally matched, so dazzlingly verbal, so witty, so “self-endeared” (as Hero calls Beatrice), and totally obsessed with each other that, frankly, who else could put up with either of them? It’s no surprise that when Hector Berlioz turned “Much Ado About Nothing” into an opera in 1862, he called it “Béatrice et Bénédict”. Claudio and Hero are the ostensible leads of “Much Ado About Nothing,” but Beatrice and Benedick are the ones that everyone remembers.

Watching Amy Acker and Alexis Denisof battle it out, in words and in a near wrestling match near the end of the film, is a supreme pleasure. Beatrice is a tough-talkin’ dame like Carole Lombard or Katharine Hepburn, and Benedick is an independent irritable guy, reminiscent of Cary Grant or William Powell. Underneath the hostility is a coursing current of love and desire, lust and fondness, which both characters struggle mightily to hide. When they finally crack, when they finally give in, it is breath-taking and emotional.

“Much Ado About Nothing” is one of the best films of the year.