Netflix’s attempted monopolization of military-focused action movies continues with “Mosul,” which ticks many of the same boxes as the streaming service’s previous offerings. Like “Extraction,” “Mosul” is produced by the Russo Brothers and stars actor Adam Bessa. Like “6 Underground,” “Mosul” is set in the Middle East, in a country struggling for liberation against oppressive countrymen. And like both of those Netflix originals, plus the Morocco-set “Close,” “Mosul” is directed and written by a filmmaker who does not hail from the region of the world that is centered upon, and implicitly criticized by, these movies. All of that is to say that “Mosul” has the veneer of a certain kind of problematic thriller that others the very individuals whom its protagonists are saving.

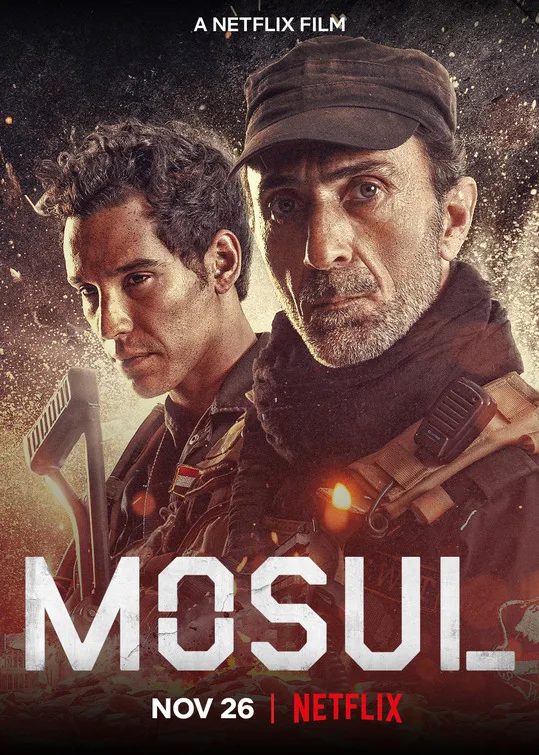

But Matthew Michael Carnahan, whose script credits include “Dark Waters,” “World War Z,” and “21 Bridges,” avoids such white-savior tropes with his directorial debut, based on true events, about the Nineveh SWAT team in Mosul, Iraq. Pairing a refusal to extend any sympathy to the Islamic State with thoughtful, if somewhat underdeveloped, commentary about Iraq’s history and relationships with the United States, neighboring Iran, and onetime foe Kuwait, “Mosul” feels grounded in a tangible sense of place and time. Although the film sometimes relies on formulaic imagery to make plain the evils of the Islamic State (orphaned children, impregnated women), it makes up for that predictability with a gripping lead performance from Iraqi actor Suhail Dabbach. As the SWAT team leader Major Jasem, Dabbach is a steely-eyed patriarch, a man who believably switches between killing Islamic State fighters, urging his “sons” and comrades to drink water during their mission, and befriending a young boy they see wandering along a dirt road. Dabbach is the heart and soul of “Mosul,” making real the unbelievable loss Iraqis have suffered after decades of war and destruction—and the sliver of hope they still hold onto for a better life.

“Mosul” is set in the same-named city in northern Iraq, which used to be a thriving metropolis with a population of nearly two million. Located on the Tigris River, Mosul is near Nineveh, an ancient Assyrian city that used to be the jewel of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in Upper Mesopotamia. After the post-Sept. 11, 2001, U.S.-led invasion of Iraq destabilized the country, the Islamic State’s presence in and control of various Iraqi cities exacerbated. In 2014, the terrorist group (which certain Middle Easterners call the pejorative “Daesh”) began creeping into the city, and when “Mosul” begins in present day, their destructive impact is clear. Establishing drone shots make clear the widespread devastation—collapsed buildings, burning cars, abandoned neighborhoods—while intertitles explain that one of the only factions feared by Daesh fighters is the Nineveh SWAT team. Made up of police officers from Mosul, who use their first-hand knowledge of the city to their advantage, the Nineveh SWAT team members are infamous for their toughness. None of them has ever switched sides and joined Daesh to save themselves, and none of them has ever been taken prisoner.

There are still good people in the city trying to defend it, and “Mosul” begins during a shootout between three Iraqi police officers and a tide of Daesh fighters. Although the Islamic State seems to be on their way out of Mosul, their dealings—trading drugs for guns, stealing cash from citizens who remain, and kidnapping and raping women—still make them criminals, and young police officer Kawa (Bessa), his uncle, and another officer are attempting to make arrests. They’re severely outmanned until Major Jasem and his men show up in Humvees decorated with a modified skull-and-crossbones logo, loaded up with guns and daggers and grenades, sporting keffiyehs and body armor. They have a strict code, checking people’s names against a gigantic list they carry to double check whether the individual is affiliated with the Islamic State, and they pick dead fighters’ pockets for cash, and they add any abandoned weapons to their own cache. Their goal is to kill any Daesh they see and reclaim the city they love, and there’s no room within that ideology for mercy.

When Kawa’s uncle is killed in the skirmish, Major Jasem offers him an opportunity to join the SWAT team and exact his own justice. Kawa’s acceptance of that thrusts him into a mysterious mission the SWAT team is desperate to complete before the Islamic State leaves the city, and what follows in “Mosul” is a series of unimaginatively shot action sequences but nuanced explorations of the Iraqi people’s struggle to live every day in a country seemingly constantly under attack. Carnahan doesn’t do anything flashy here: There are no 12-minute single takes, as in “Extraction,” and although most of the fighting happens in buildings the team is clearing, there are no creative uses of stairwells, as in “The Raid.” “Mosul” is more interested in what happens after Daesh is defeated, and various scenes wonder about the future of this place and its people. Major Jasem’s tendency to pick up garbage, whether the SWAT team is in a decimated apartment building or in the secret hideout of an Iranian-backed militia group, and properly place it in a trash can is a clue into his desire to clean up the city where he’s lived his whole life. Kawa, only two months into the job, must reconcile the fact that many of his police colleagues saved themselves and switched sides rather than truly working to serve and protect. And various other SWAT team members speak of the relatives they’ve lost or the wounds they themselves have suffered, stories that serve as as emotional fuel for their understandable ruthlessness.

Some of Carnahan’s choices rely on certain Western stereotypes to underscore the awfulness of the Islamic State (when an intertitle refers to their campaign of rape, torture, and murder as being on a “Medieval scale,” as if the Crusades weren’t initiated by the Catholic Church; a man ripping a headscarf off a young girl in a scene coded as liberation), but what “Mosul” gets right more often is its prioritization of the Iraqi perspective, and the weight of all this violence. Major Jasem gets into a heated argument with a foreign agent about the history of the Iraq; the altercation is pure melodrama, but Carnahan understands the allure of nationalism. Kawa sees the more-seasoned men taking selfies with the bodies of dead Daesh fighters but can’t bring himself to mimic their poses; his actions toward the film’s conclusion, however, demonstrate his swift hardening. “We can rebuild everything. We just have to kill them all first,” Major Jasem says, and although “Mosul” underwhelms with its action sequences, Dabbach’s performance and the film’s commitment to that search-and-destroy ideology from the viewpoint of Iraqis themselves create some undeniably satisfying moments.

Now streaming on Netflix.