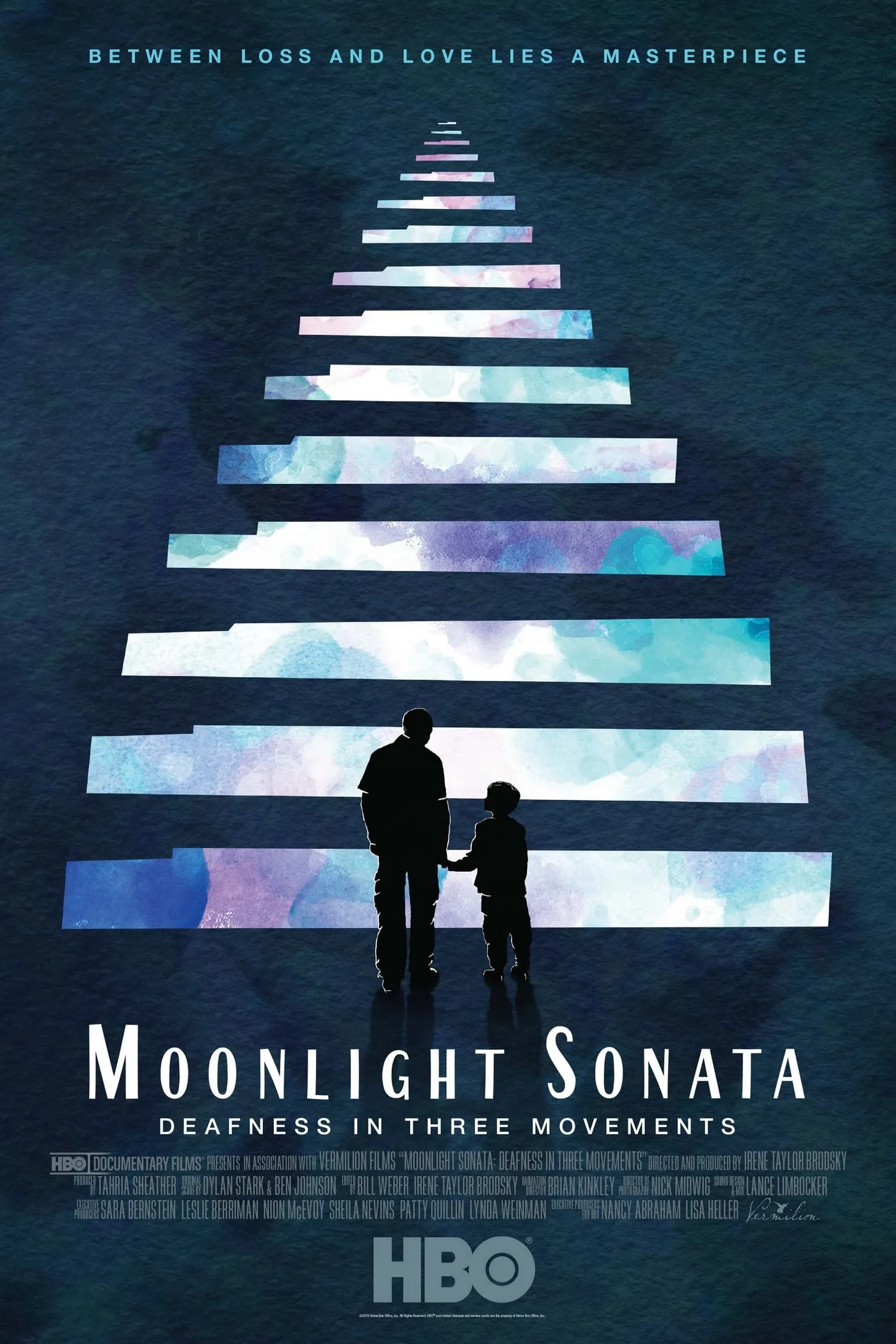

The documentary “Moonlight Sonata” is about a deaf boy named Jonas trying to play a Beethoven piece on the piano, even though he’s been warned he’s not ready for it yet. Meanwhile, his deaf grandparents—Paul and Sally—grapple with the realities of age.

The boy’s determination to master the piece is sparked by the fact that Beethoven was deaf, and wrote “Moonlight Sonata” to come to terms with his condition; Paul and Sally have been married for nearly 60 years, and didn’t get cochlear implants until they were in their sixties (an experience captured in Brodsky’s 2007 documentary “Hear and Now”). Directed by Irene Taylor Brodsky—Jonas’ mother and Paul and Sally’s daughter—this is the kind of film where simplicity generates feeling, and meanings are mainly carried through images of people doing things, going places, talking to each other, and sitting in close-up, lost in thought.

Paul, an inventor of communications devices for the hearing impaired, bought the director her first camera when she was a just a girl and taught her how to use it. The images of the grandfather’s invention (which looks like a hybrid of a typewriter and a piano) connect with the grandson’s attempts to master Beethoven as well as the daughter’s quest to evoke her family’s difficulties through images and sounds. Everywhere you look (and listen), there is language, imperfectly striving to capture the moments that define our lives.

This artistic reaching-out across the centuries is made dynamic in scenes of Jonas, who got cochlear implants as a toddler but sometimes takes them out at the keyboard, practicing with his teacher, Colleen. We should all be so lucky as to have somebody like her as an instructor. Colleen demands commitment and focus, but while she’s not above busting chops, she’s never cruel, and she doesn’t believe in perfection, only improvement. She honors Jonas’ tenacity by telling him the truth instead of what he wants to hear. When he improves, she gives him a peppermint. When he asks for more than one, she says no, unless he makes her laugh.

Their athlete-and-coach dynamic is as inspiring as anything in a sports drama. Brodsky leans on the comparison a bit too hard sometimes, even throwing in the equivalent of a training montage near the end. There are other moments where her nerve fails her, and she comes in with voice-over narration that’s thoughtfully written and subtly performed but not always necessary, lays on music where silence was all that was needed, or otherwise fails to embrace the innate power of the extraordinarily intimate moments she’s captured (especially at the end, which rushes through a scene that deserved to unfold out at length).

But such lapses are noticeable only because there are so few of them. For the most part, this is an exceptional movie that works on several layers at once, with such tunnel-vision (like Jonas at his keyboard) that it seems not to care whether you notice how much thought went into its creation. “Moonlight Sonata” is about music, language, and music-as-language. It’s about ability and disability, youth and old age, memory and experience. And it’s a film about how the gifts of discipline and artistic expression are paid forward through generations. It’s a powerful film about parents and children, told with enough restraint that its more affecting moments may sneak up on you.

But mainly it’s about the boy at the piano, chipping away at a sonata, day by day, week by week, dreaming at first of mastering it, then of getting through it with no mistakes, then realizing that in music, as in life, just getting through it is challenge enough.

It isn’t until deep into “Moonlight Sonata” that you start to realize how many patterns Brodsky has woven into the fabric of this tale—everything from the three-movement structure, which mirrors the three generations of Brodskys, to the repeated shots of flying creatures (ducks and bats, some live-action, others animated) flitting across the screen in V-formations and in whirling clouds that change shape and direction on a dime. At various points, Beethoven, Jonas and Paul are all associated with a bird that travels alone, always remaining in sighting distance of a flock but never allowing himself to become part of it. In time, we associate each member of the Brodsky family with that bird, flying solo yet always in view of the flock, following its own course, wherever it leads.