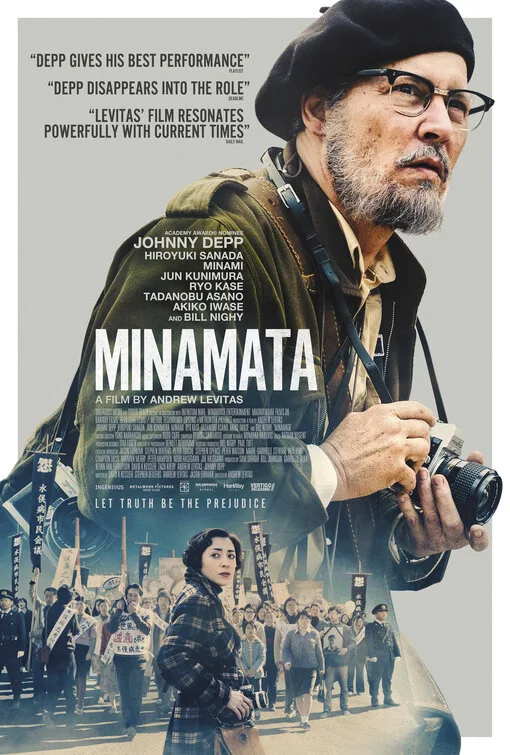

“Minamata” showcases its desire to be an important movie in almost every frame. It tries to be a character study, a commentary on the power of photojournalism, and a study in how the large profit margins of major corporations can attract those without moral compasses. Sadly, it too often misses the first of those three narratives by underlining and emphasizing the second pair, and character is really the most important thing about films like this. A “message movie” only works because of the characters who convey it. We admire films like “Spotlight” and “Dark Waters” not solely because of the true stories they unveil but because of how those messages are embedded in character dramas. Leading man Johnny Depp is up to the challenge, and he gives a finely tuned performance here that kind of feels like his first “old man” turn, and he’s matched by a charming piece of work from Minami, but “Minamata” is weighed down by self-important direction that loses the human beings in this story by prioritizing the headlines.

The script by David K. Kessler, Stephen Deuters, Jason Forman, and director Andrew Levitas—having four cooks in the kitchen here could explain the lack of stylistic and narrative cohesion—opens in New York in 1971. W. Eugene Smith (Depp) is far past his prime as a respected WWII photojournalist, haunted by what he’s seen and aware of his increasing obsolescence. He drowns his sorrows with bottles—both pill and liquor—but maintains one of his few professional relationships with Life magazine editor Robert Hayes (the always-welcome Bill Nighy, sadly reduced to a few scenes here in a journalism office).

What looks like it will be his final commission for Life sends Smith to the city of Minamata, Japan, which has been slowly poisoned for years by a company called Chisso; they’ve been dumping mercury into the water supply, leading to a severe neurological disease. First discovered in 1956, Minamata Disease has impacted thousands of people, and Smith goes to the prefecture to bring the story to the world and put more pressure on Chisso to do something about it. He ends up getting to know the locals there, including the woman (Minami) who convinces him to come in the first place, and overcomes his own personal demons to be an ally to those who need him.

Smith’s photojournalism gave a human edge to a horrifying story, and it’s clear that this is the aspect that most inspires Levitas, who sometimes feels like he sees a little bit of himself in Smith. Sadly, photojournalism doesn’t have the same impact it did in the print era of the ‘70s, so Levitas would likely argue that the people of Minamata need filmmakers to tell their stories now. And I bet he would make a fascinating documentary about both Smith and the people he encountered on the most important assignment of his life.

The problems come when Levitas tries to translate that passion into interesting drama. He hired great people in terms of craft, working with the great Benoît Delhomme (“At Eternity’s Gate”) to give the entire production a charged visual acumen. And the legendary Ryuichi Sakamato provides a lovely score. But these master craftsmen almost enable Levitas’ fatal flaw, one that really lands with a final photo montage of disasters like Minamata from around the world, making it clear how much the producers here feel like they’ve made a definitive film instead of just a heartfelt one.

A film like “Minamata” doesn’t need to tell every story like it, look perfect, or have a mesmerizing score. It needs to be a little edgy and gritty and human to feel true. Otherwise, it feels like something we look at through a lens, something we observe and admire but can never get our hands on to truly feel.