On January 6, 2002, Boston Globe subscribers picked up their local paper and saw the front page headline: “Church Allowed Abuse by Priest for Years.” The story, written by Michael Rezendes, a reporter on the investigative “Spotlight” team, was massive, in word-count and impact, but it was just the beginning. Two more Spotlight stories on the same topic ran that day, with more to follow. The uproar from the Spotlight stories (The Boston Phoenix, an alternative weekly, had covered church sexual abuse but it didn’t have the circulation of the Globe) was so sustained that by December 2002, Cardinal Bernard Law, the Archbishop of Boston, stepped down in disgrace, saying in a statement, “To all those who have suffered from my shortcomings and mistakes I both apologize and from them beg forgiveness.” (Pope John Paul II gave him a position in Rome, where Law remains to this day.) The Spotlight team won a Pulitzer Prize in 2003 for their reporting. These events are familiar to everyone by now, but those first Spotlight stories are painfully familiar to Boston Catholics (my family is Boston Irish-Catholic), and it was the first news story to dominate everyone’s conversations since September 11th only a few months prior.

Tom McCarthy’s superb “Spotlight,” co-written by McCarthy and Josh Singer, is the story of that investigation. “Spotlight” is a great newspaper movie of the old-school model, calling up not only obvious comparisons with “All the President's Men” and “Zodiac,” two movies with similar devotion to the sometimes crushingly boring gumshoe part of reportage, but also Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell shouting into adjacent phones in “His Girl Friday.” At a late moment in “Spotlight,” there’s an image of the presses printing off the edition that carries the church abuse story. Such a scene is so de rigueur in newspaper movies that it borders on cliche, but in “Spotlight” it is a moment of intense emotion. The truth in that edition, the evil it describes, will be a wound in the psyche of millions, but it must come out.

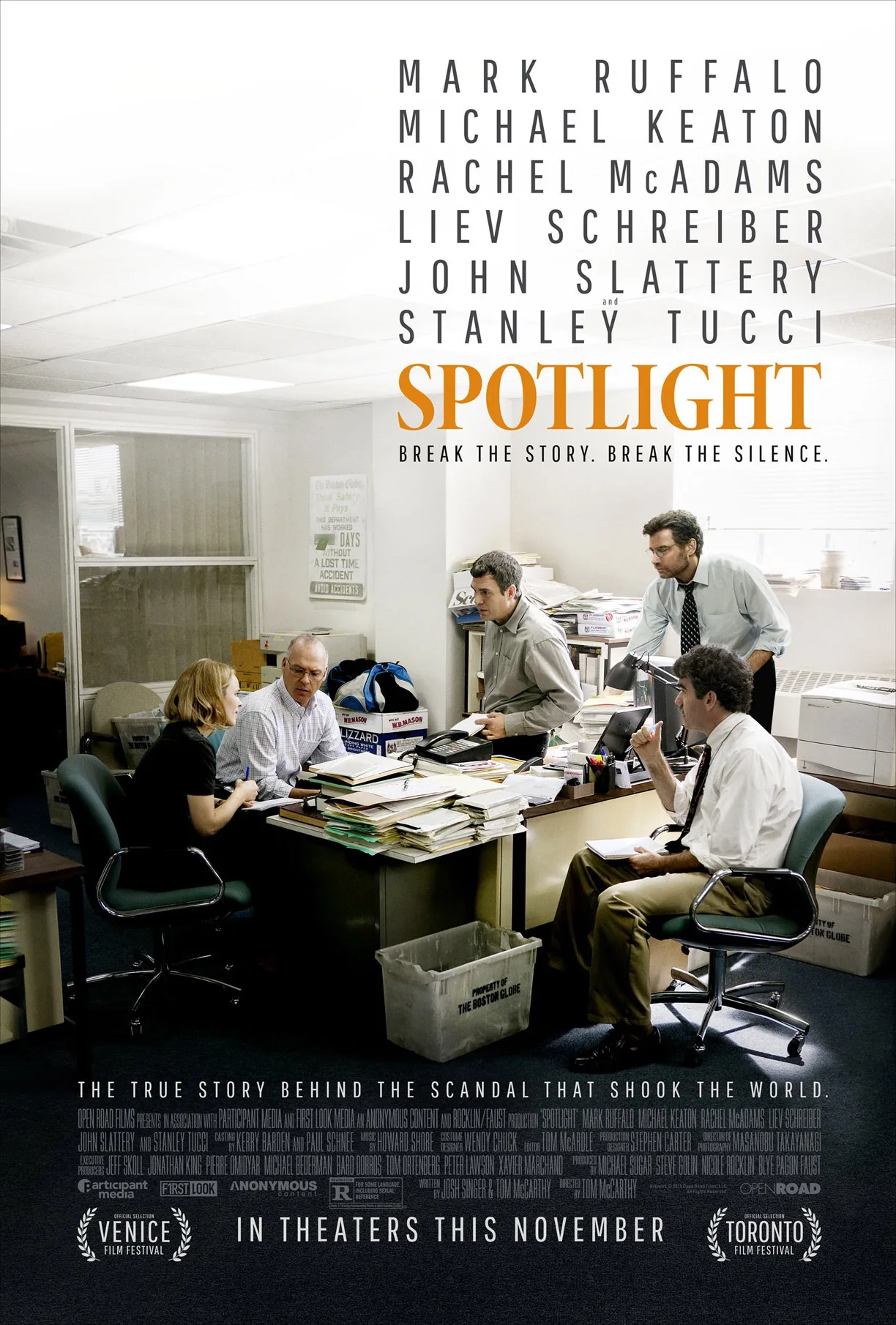

The Spotlight team is editor Walter “Robby” Robinson (Michael Keaton), and three reporters, Michael Rezendes (Mark Ruffalo), Sacha Pfeiffer (Rachel McAdams), and Matty Carroll (Brian d’Arcy James). John Slattery plays Globe managing deputy editor Ben Bradlee Jr.. All of the reporters are locals, and everyone has some connection to the Catholic Church (referred to as only “The Church”). When a new editor, Marty Baron (Liev Schreiber), comes on board, he is perceived as an outsider because he’s not from Boston at all (he is first seen boning up on the city by devouring “The Curse of the Bambino.”) In an initial meeting with Robby, Baron brings up a recent piece by a Globe columnist about the Boston archdiocese’s potentially shady handling of various abuse cases. Baron suggests the story could be perfect for the Spotlight team. Robby hesitates, but Baron gently pushes: “This strikes me as an essential story for a local paper.” It’s a great line, and it’s so underplayed by Schreiber that you might miss its effectiveness. This goes for his entire performance. Right before the church-abuse edition goes to print, they all meet in Marty’s office, and he looks through a hard copy of the story, crossing out words, murmuring to himself, “Adjectives.” That is a newspaper man.

Holed up in a cluttered basement office, the Spotlight team exhibit the behavior of people who spend more time with one another than they do with their own families. Personal details about their lives are at a minimum. Sacha goes to church every Sunday with her grandmother, a ritual she finds increasingly painful. Rezendes’ marriage is on the rocks. Matty has a couple of kids, and a big magnet on his refrigerator emblazoned with an American flag and “Remember 9/11” on it. We know who these people are.

At first the team focuses on one former priest, John J. Geoghan, alleged to have molested many children years ago. But Baron urges them to remember that the story is bigger than just one “bad apple” priest. He wants to go after the whole system. The corruption is obviously systemic, but the key issue becomes: did Cardinal Law know? That’s the big game Spotlight is after. “The Curse of the Bambino” may have taught Baron about Red Sox Nation, but a meet-and-greet with Cardinal Law (a creepily sincere Len Cariou) during Baron’s first week on the job is even more illuminating. Baron is stunned at Law’s assumption that the Boston Globe would work with the Catholic Church.

Sacha and Michael question the adult victims willing to come forward, who are so traumatized they can’t find the words to describe what was taken from them. A couple of lawyers (played by Billy Crudup and Stanley Tucci) sit on opposite ends of the spectrum of dealing with the Catholic Church from a legal standpoint.

McCarthy and his entire team, from production designers to location scouts to extras casting directors, get Boston right. Different neighborhoods (Back Bay, Southie) are used as shorthand for entire worlds. There are clear class divides (predator priests often worked in low-income neighborhoods, targeting boys who needed father figures). The atmosphere is very “Boston”: having a beer on the back porch in the dead of winter or arguing about work over hot dogs at Fenway. Boston, with its confusing colonial-era streets and church spires jutting into the sky on practically every corner, is the soul of the movie. “Spotlight” feels local.

“Spotlight” also shows a deeper truth, the level of psychological trauma brought on by abuse, not just to the victims, but to horrified Catholics everywhere. “Spotlight” takes faith seriously. An ex-priest turned psychiatrist is an important source, and when he’s asked how Catholics reconcile the abuse scandal with their faith, he replies, “My faith is in the eternal. I try to separate the two.” Mark Ruffalo modulates his performance over the course of the film at a world-class level, moving from a patient dogged investigator to a rumpled maniac racing through courthouses, chasing down cabs and screaming at his boss. In a raw moment, he confesses to Sacha that even though he stopped going to church years ago, he always assumed that one day he would go back. “I had that in my back pocket,” he says, glancing at her with a flash of anguish. “Spotlight” makes the issue of lost faith visceral by taking the time to let it breathe, letting it play its part in the story.

The newspaper world has changed a lot since 2002. Things look pretty grim. But good long-form journalism still exists (the recent New York Times series about the conditions for nail salon workers is a good example). Such work is as important now as it has ever been. “Spotlight” is the kind of movie where a scene showing a group of reporters huddled over church directories, taking notes in silence, becomes a gripping sequence. (It’s reminiscent of the row of mission control guys in “Apollo 13,” whipping out their slide rules as one, thereby almost single-handedly expanding the concept of heroism.) “Spotlight,” with all its pain and urgency, is a pure celebration of journalists doing what they do best.