In formula action pictures, there are always setup scenes early in the movie that trigger payoff scenes later on. “Metro” is a movie so preoccupied with its chases, stunts and special effects that it never gets around to the payoffs. That’s not a criticism, just an observation. Leave out the setups *and* the payoffs, and you’d have wall-to-wall action, which is the direction I suspect we’re heading in.

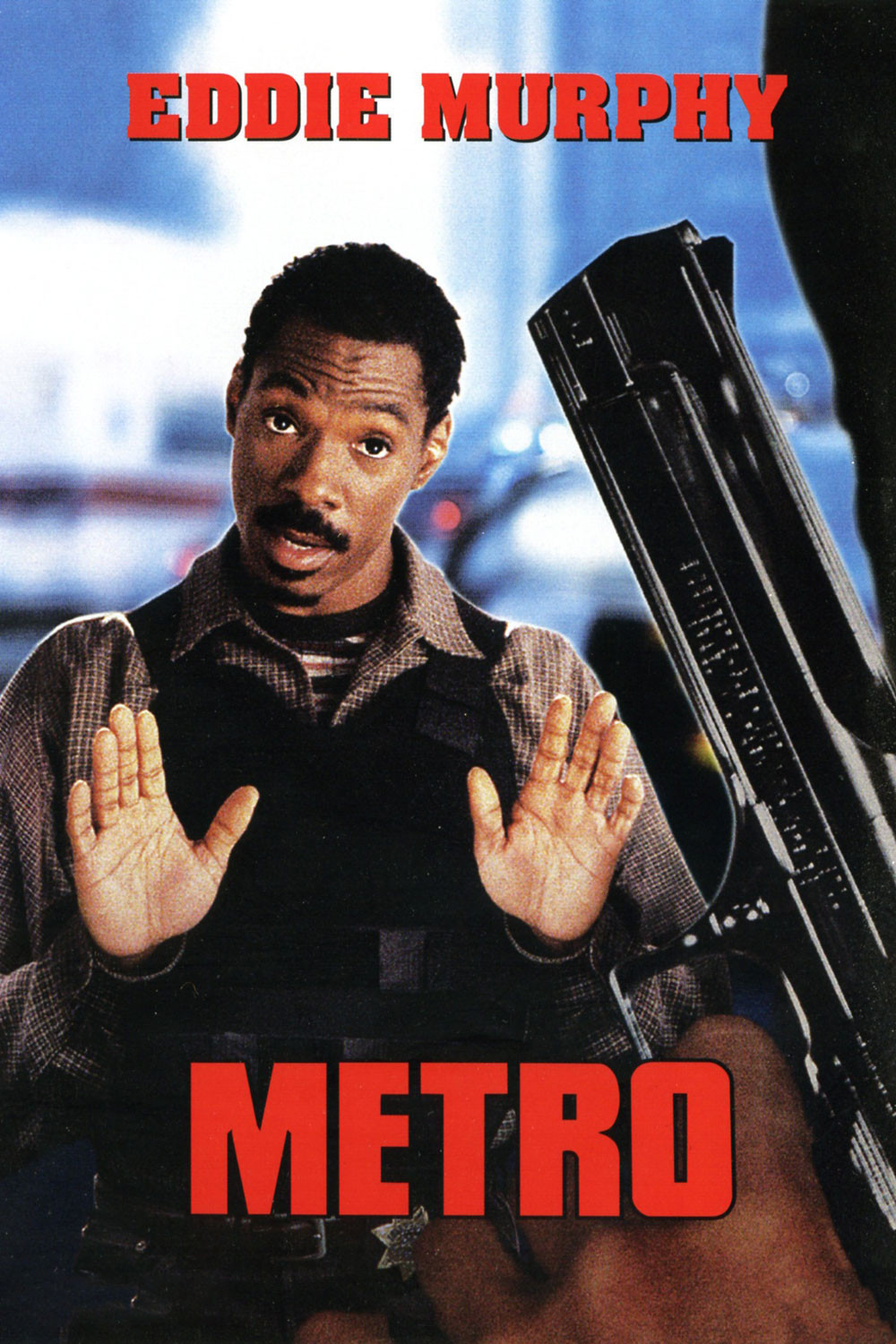

“Metro” stars Eddie Murphy in a muscular, energetic performance as Roper, a star hostage negotiator for the San Francisco Police Department. He’s the guy who walks unarmed into the bank where the robber is holding a gun to a hostage’s head and gets the guy talking. Murphy has always been a good talker, and he has fun with some of this dialogue. Taking a bag of doughnuts to a manic madman, Roper explains, “I’m duty bound under my oath as a negotiator to take out this wounded man.” And he does.

This opening scene of course has nothing to do with the rest of the movie. Action movies always start in the middle of a crisis, establish the hero, and then move into the story. Usually the early crisis is followed by a quiet domestic scene (Roper meets his former girlfriend) and the introduction of the police chief, etc., before another crisis develops. Oh, and the cop has to meet his New Partner.

“Metro” makes all the early stops, which makes it interesting that it never doubles back to refer to them again. For example: 1. Roper gets a new partner named McCall (Michael Rapaport) who is a marathon runner, can lip-read, is a sharpshooter, etc., but has never done hostage negotiations before. The formula calls for the veteran to resent the kid and make it hard for him. Not here. Roper asks his chief for a raise, gets it and takes the kid to the racetrack.

2. After a friend of Roper’s is killed by Korda (Michael Wincott), the movie’s homicidal diamond thief, Roper vows revenge. Then, of course, the chief takes him off the case. Roper continues to chase the guy anyway–no one says a word to reprimand him, and his badge and gun are never taken away.

3. In a mockup of a grocery store, Roper uses department store mannequins to represent stickup guys, and rehearses his new partner in the methods of handling such a situation. This will inevitably pay off when the kid has to handle such a situation, right? Wrong.

4. Roper is seen as a compulsive gambler. This will have something to do with the plot, right? Wrong again. It’s a meaningless character detail.

5. Roper’s girlfriend Ronnie (Carmen Ejogo) has left him for a baseball star. The two men meet briefly, and coldly, at her apartment. Then she gets back with Roper. The baseball player will turn up later, angry and possibly dangerous, right? Nope, he’s never seen again.

These aren’t loose threads because the plot doesn’t matter, anyway. They’re simply punctuation marks between the extravagant stunt scenes. The reason to see “Metro” is because it has two ingenious action sequences. One occurs when Korda, fleeing Roper, leaps aboard a San Francisco streetcar and kills the driver. The streetcar speeds downhill out of control, crashing into dozens of cars, and Roper and McCall chase it in a vintage Cadillac before Roper jumps onto the streetcar, then back into the Caddy, which they steer broadside in front of the streetcar, slowing it before it plows into dozens of victims at the bottom of the slope.

This is of course impossible (the Caddy’s tires don’t even blow after scraping sideways for a couple of thousand yards), but so what? It’s fun, and skillfully directed by Thomas Carter. And there’s an ingenious scene later in the film where Ronnie, the hapless girlfriend, is strapped to a piece of machinery that functions in exactly the same way that sawmills did in old silent movies: If Roper takes his hand off the red button, the girl will be cut in two. If he doesn’t, he’ll be killed. Neat.

The movie also has fun with horror movie cliches. Ronnie keeps closing her bathroom mirror so we can see the killer behind her–and the movie’s music swells ominously–but there’s no killer. She calls for her dog, and the dog doesn’t come. More swelling music. But the dog isn’t dead. And “Metro” should get a gold star for being the first movie in the history of San Francisco to stage a chase through Chinatown without having the cars get stuck in the middle of a parade. On the debit side, after Roper knows the villain has escaped from jail and vowed revenge, he lets Ronnie go back into her apartment alone. “I’ll be right back,” she says, when as the characters in “Scream” observe, hardly anyone who says that ever is.

The movie works well on its chosen level. The big action scenes are cleverly staged and Eddie Murphy is back on his game again, with a high-energy performance and crisp dialogue. Rapaport makes a good foil–stalwart, with good reaction shots–and Wincott is a smart, creepy killer. There are some nice twists. Perhaps it is even a good thing that this is the first cop buddy movie that uses all the cliches from the first half of the formula and none from the second. It’s not like I missed them.