Stanley Kauffmann argues in the latest New Republic that Christ might have enjoyed Monty Python’s “Life of Brian” because he had a sense of humor, manifested by his occasional puns in the Bible. That’s more than can be said for those representatives of established religions who have condemned the movie for being blasphemous.

As Kauffmann rightly points out, “Life of Brian” does not mock the life of Christ, but has its fun with the life of one Brian, born on the same day but in the next stable. The movie shows Christ only twice — once in the manger, suitably illuminated by a halo, and the second time from the very back rows of the crowd gathered for the Sermon on the Mount (“I can’t hear him,” one of Brian’s contemporaries complains. “What did he say? The Greek shall inherit the Earth? Blessed are the cheesemakers???”).

Perhaps you don’t find that funny. Perhaps you don’t find Monty Python funny; the troupe’s peculiarly British brand of humor is sometimes impenetrable to Americans. But is it blasphemous? Hardly. In terms of actual disrespect shown to Biblical legend, such epics as “Samson and Delilah” and “King of Kings” (the Jeffrey Hunter version) are miles more hypocritical — they appeal to our base instincts while pretending to edify our enlightened ones, a Hollywood process by which one of the most publicized characters in the Bible somehow came to be Salome.

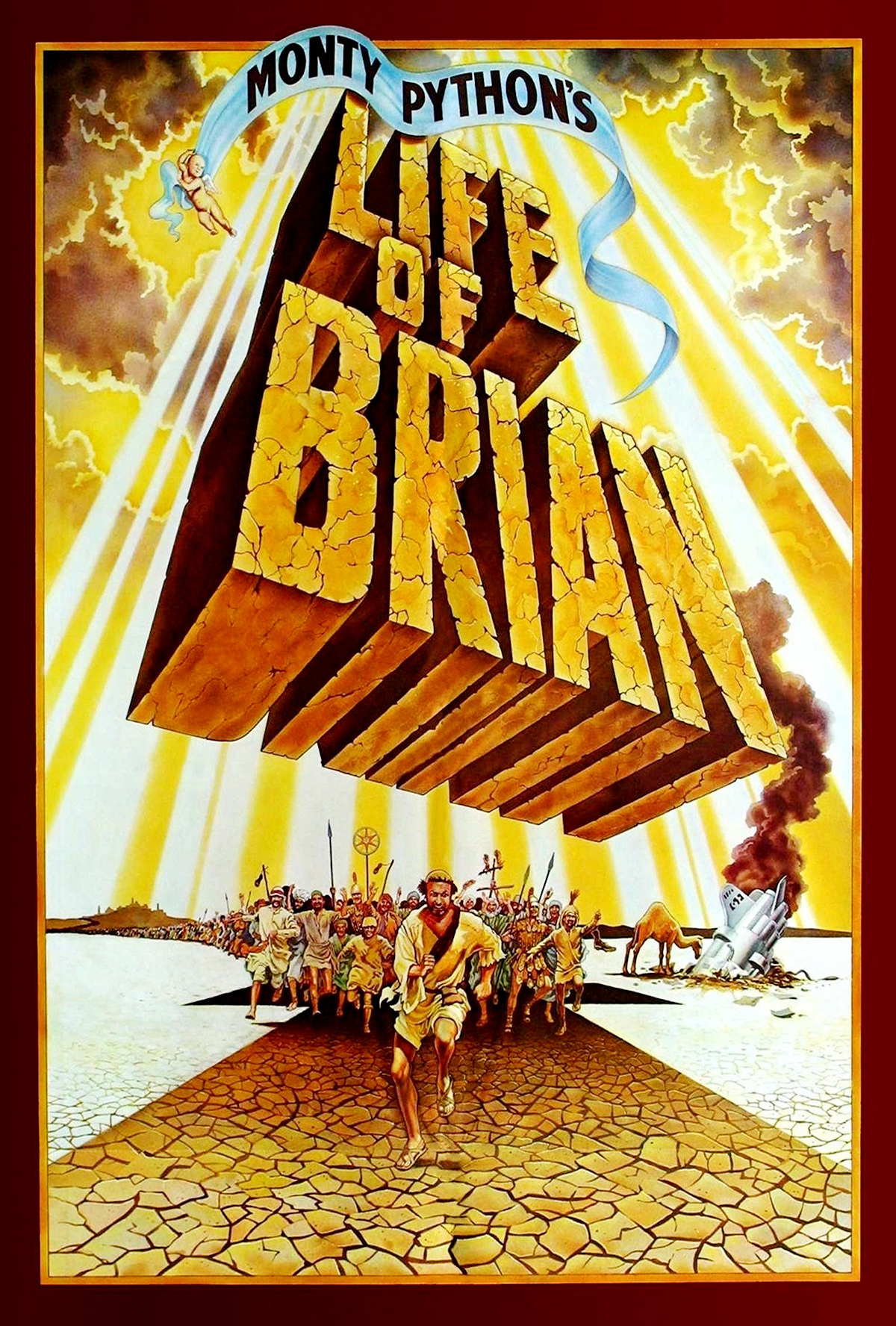

“Life of Brian” is really more about movies than about religion: It finds its origins in those countless Biblical epics where Roman legions marched up and down while intrigue waxed hot and heavy in Pilate’s inner court. The movie is the most ambitious project yet for the Python people, but had its inspiration, no doubt, in “Monty Python and the Holy Grail,” which took on the King Arthur legends.

The approach is much the same: The Python personalities are plugged into a set of historical movie cliches, and then the situations are treated with the utmost logic. What would have happened at your typical pre-Christian stoning? How did women find out what was going on when they were allegedly banned from public meetings? What if Pontius Pilate spoke with a lisp? A few slight lapses in reality are permitted, to be sure, as when Brian falls from a high tower and is saved by an alien spaceship that happens to whisk by at that very moment.

If there is a problem with the Monty Python approach to comedy, it’s that it is sometimes so British, so sly and so old-school that jokes are being made we can’t quite understand. The same thing often occurs with the cartoons in Punch, the British weekly humor magazine: There are perfectly clear drawings with captions in plain English, but an American reader just doesn’t get the joke.

What’s endearing about the Pythons is their good cheer, their irreverence, their willingness to allow comic situations to develop through a gradual accumulation of small insanities. American comedians seem to share, as a group, a need to be accepted, understood and approved of — which is why even an insult artist like Don Rickles allows his act to degenerate into smarmy sweetnesses.

The classic British comedians, on the other hand, seem to have become permanently disenfranchised even before first appearing in public; they have developed dottiness into an art form and refined it into an attitude. “Life of Brian” is so cheerfully inoffensive that, well, it’s almost blasphemous to take it seriously.