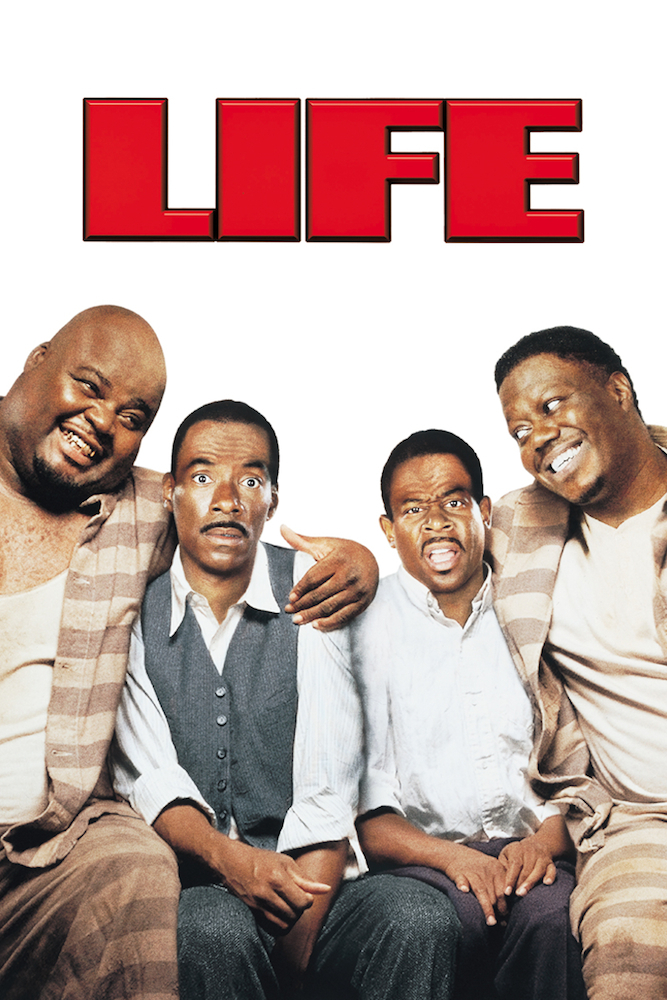

Eddie Murphy and Martin Lawrence age more than 50 years in “Life,” the story of two New Yorkers who spend their adult lives on a Mississippi prison farm because of some very bad luck. It’s an odd, strange film–a sentimental comedy with a backdrop of racism–and I kept thinking of “Life Is Beautiful,” another film that skirts the edge of despair. “Life Is Beautiful” avoids it through comic inspiration, and “Life” by never quite admitting how painful its characters’ lives must have been.

The movie is ribald, funny and sometimes sweet, and well acted by Murphy, Lawrence and a strong supporting cast. And yet the more you think about it, the more peculiar the movie seems. Murphy created the original story line, and Ted Demme (“The Ref”) follows his lead; the result is a film that almost seems nostalgic about what must have been a brutal existence. When was the last time that a movie made prison seem almost pleasant? “Life” opens in 1932 in a Harlem nightclub, with a chance encounter between a bank teller named Claude (Lawrence) and a pickpocket named Ray (Murphy). They both find themselves in big trouble with Spanky, the club owner (Rick James), who is in the process of drowning Claude when Ray saves both their lives by talking them into a job: They’ll drive a truck to Mississippi and pick up a load of moonshine.

The trip takes them into Jim Crow land, where Claude is outspoken and Ray more cautious in a segregated diner that serves “white-only pie.” Then they find the moonshiner, load the truck and allow themselves to get distracted by a local sin city, where Ray loses all his money to a cheat (Clarence Williams III) and Claude goes upstairs with a good-time girl. The cheat is found dead; Claude and Ray are framed by the sheriff who actually killed him and given life in prison.

The early scenes move well (although why was it necessary to send all the way to Mississippi for moonshine, when New York was awash in bootleg booze during Prohibition?). The heart of the movie, however, takes place in prison, where after an early scene of hard physical labor, life settles down into baseball games, talent shows and even, at one point, a barbecue. Bokeem Woodbine plays Can’t Get Right, a retarded prisoner who hits a homer every time at the plate, and Ray and Claude become his managers, hoping to get a free ride out of prison when he’s recruited by the Negro Leagues. But it doesn’t work that way, and life goes on, decade after decade, while the real world is only hearsay.

Demme has two nice touches for showing the passage of time: Prison inmates are shown simply fading from the screen, and in the early 1970s Claude gets to drive the warden (Ned Beatty) into nearby Greenville, where he sees hippie fashions and his first afro haircut. Meanwhile, Rick Baker’s makeup gradually and convincingly ages the two men, who do a skillful job of aging their voices and manners.

All of this time, of course, they dream of escaping. And they maintain the fiction that they don’t get along, although in fact they’ve grown close over the years (comparisons with “The Shawshank Redemption” are inevitable). Ray remains the realist and compromiser, and Claude remains more hotheaded; the warden likes them both and eventually assigns them to his house staff. But what are we to make of their long decades together? That without the unjust prison term, they would never have had the opportunity to enjoy such a friendship? That prison life has its consolations? That apart from that unfortunate lifetime sentence, the white South was actually pretty decent to the two friends? “Life” simply declines to deal with questions like that, and the story makes it impossible for them to be answered. It’s about friendship, I guess, and not social issues. Murphy and Lawrence are so persuasive in the movie that maybe audiences will be carried along. Their characters are likable, their performances are touching, they age well, they survive. And their lives consist of episodes and anecdotes that make good stories–as when the white superintendent’s daughter has a black baby, and the super holds the kid up next to every convict’s face, looking for the father. That’s a comic scene in the movie; real life might have been different.

But life flows along and we get in the mood, and by the end we’re happy to see the two old timers enjoying their retirement.

After all, they’ve earned it.