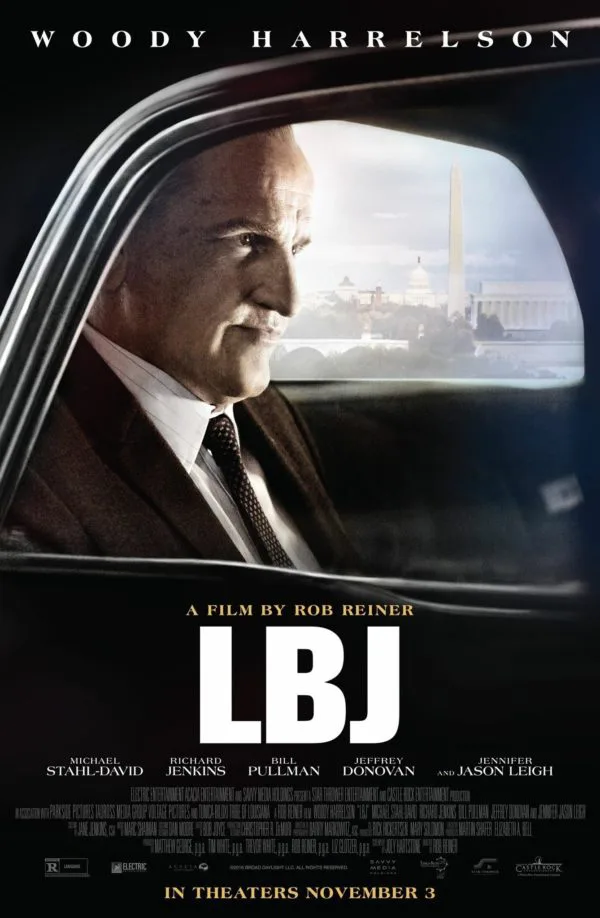

Fortified by vivid, compelling performances from Woody Harrelson and Jennifer Jason Leigh as Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson, Rob Reiner’s “LBJ” captures a tumultuous political era and one of its most profanely colorful leaders with a good deal of insight and emotional torque. Though the film understandably leaves out much about Johnson’s career to focus on his growing commitment to Civil Rights, it does so with verve and conviction before, alas, turning more soft-edged and conventionally hagiographic as it nears the finish line.

The film’s historical frame represents some interesting choices on the part of screenwriter Joey Hartstone. While Johnson’s legacy includes such milestones as his Great Society legislation, Head Start, Medicare and Medicaid as well as his escalation of the Vietnam War, “LBJ” largely ignores the events of his presidency to focus on what came before, in the years 1959-63: first, his power as the Senate majority leader; then, his years as vice president, when he felt largely neutered and marginalized until fate catapulted him to the pinnacle of power.

The effectiveness of this approach stems from the fact that it centers on the time in his life when, between passages when he exercised enormous influence, Johnson was challenged by being rendered a mere spear-carrier in the glamorous Kennedy retinue. Such episodes in a politician’s life – internal exiles, if you will – entail psychological struggles that test his character, sagacity and resolve to the extreme. Hartstone’s smart, flavorful script makes the most of this rough passage.

In what initially seems a somewhat corny contrivance, but later proves its dramatic worth, the film intersperses the first two-thirds of its narrative with a depiction of the events of November 22, 1963, with the Johnsons arriving in Dallas and following President and Mrs. Kennedy in the motorcade that will take them through downtown. At this point, Johnson is the quintessence of a background figure, and obviously not happy about it. But the film soon jumps back four years, to his time as a kingpin of the Senate, when his powers are manifest to all.

We see him commanding a roomful of aides, barking orders, cajoling, cussing, juggling telephones, even playfully threatening a subordinate with castration. This is the grinning, arm-twisting, deal-making LBJ of legend, and Harrelson gives him to us full-bore. Though the actor doesn’t have as much physical resemblance to Johnson as did the Bryan Cranston of “All the Way,” and thus must make use of ample make-up and prosthetics, he energetically conveys both Johnson’s blustery personality and evolving internal struggles.

In some ways, the most important relationship LBJ has in the film is with veteran Senator Richard Russell (Richard Jenkins), who, as leader of the Senate’s Southern caucus, has been successfully opposing all Civil Rights legislation for decades. Johnson has a great deal of personal sympathy for Russell and, as a Southerner himself, understands the resistance of whites to changes in the laws affecting race. Yet he also understands the Northern position too. As he puts it, he “speaks both languages,” which indeed helps explain his pivotal role in history.

Come 1960, Johnson reaches a crossroads when John F. Kennedy (Jeffrey Donovan) beats him for the Democratic nomination for President. LBJ regards JFK as a “show horse,” and himself as a “work horse” and therefore more suited to taking on the work of running the nation; so when Kennedy offers him the Vice Presidential slot, he not only has to deal with the ignominy of a de facto political demotion, he does so facing the active opposition of bratty Robert F. Kennedy (excellent Michael Stahl-David), who resents having such a relative rube on the ticket.

The LBJ-RFK conflict—with JFK as bemused moderator—continues after Johnson successfully attempts to make the Vice Presidency a greater, more efficacious power base than it has been before, and also faces the rising pressures for meaningful Civil Rights legislation. Then comes the watershed moment of Dallas. The film renders this dark day with wrenching immediacy and such pungent details as LBJ refusing to leave Dallas without Kennedy’s body.

Thereafter there’s both humor and political urgency in Johnson’s trying to persuade JFK’s young Ivy League circle of aides to stay on and help him make the transition, an effort that includes embracing the Civil Rights legislation that Kennedy had hoped to introduce. Throughout these and earlier battles, LBJ is bolstered by the unflinching calm of Lady Bird, who’s brought to life with almost uncanny exactitude in Jennifer Jason Leigh’s fine performance.

In its final act, the film unfortunately devolves toward TV-movie conventionality by ending on the high note of Johnson announcing the legislation that will produce the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In reality, of course, LBJ’s career went on to include both triumphs and the tragic Vietnam escalation that effectively destroyed his presidency. As to why “LBJ” wouldn’t try to show both the dark and the light, I was reminded of a director recently complaining of an actor that “he doesn’t understand that not everything is ‘the Hero’s Journey.’”

Indeed “the Hero’s Journey” is one of those rudimentary screenwriting concepts that turns into a blight when it’s over-applied. Oliver Stone’s “Nixon” had the courage and insight to embrace the tragic elements in its protagonist’s story. If “LBJ” had done the same, a very good film might have a become a truly exceptional one.