In the annals of serial killers, where the relentless parade of inhuman acts blurs the distinctions, Carl Panzram has a niche of his own, as one of the most vicious, degenerate criminals of his time. After beating a prison worker to death, he was hanged in 1930, pausing on his way to the gallows long enough to dash off a note to opponents of capital punishment: “The only thanks you or your kind will ever get from me for your efforts on my behalf is that I wish you all had one neck and I had my hands on it.” “Killer: A Journal of Murder” is the fuzzy-headed story of a prison guard who befriended Panzram, who tried to understand what made such a violent man the way he was. The guard, Henry Lesser, came from a middle-class family that could not comprehend his career choice. Soon we begin to understand. After Panzram is punished by being beaten for an escape attempt, Lesser feels sympathy and slips him a dollar bill, which would buy a lot of smokes and candy bars. Soon Lesser began supplying Panzram with writing supplies; the journal that Panzram wrote was kept for many years by Lesser, who found a publisher for it around 1960. In the journal, Panzram recounts a lifetime of carnage. In alternating chapters, two crime reporters document the truth of most of his claims.

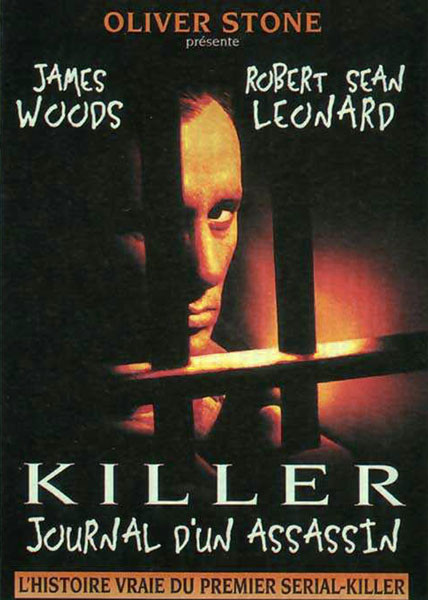

The film “Killer: A Journal of Murder” opens with the memories of Lesser as an old man. He seems to recall Panzram with nostalgia, as a man who could have redeemed himself, who needed only to be understood. Then the movie flashes back to the young Lesser (Robert Sean Leonard), who goes to work at Leavenworth and first meets the killer (James Woods). Gradually the two men become … not friends exactly, but bound together in tentative trust.

The film was written and directed by Tim Metcalfe, who found a copy of Panzram’s journal in a used-book store, read it and spent five years getting it onto the screen. He does not, however, ask the right questions about Lesser, and the film softens some hard edges.

Why did Lesser choose work as a prison guard, and why was he immediately and strongly attracted to the most evil man in the prison? Why not choose a more deserving prisoner? Is there a whiff of grandiosity here, a desire to seem saintly by facing up to the worst the human race has to offer? Is it the Stockholm complex, with the guard playing the role of hostage? Although Panzram is nominally the prisoner, he is so brilliant and ruthless that there are many times when he could have killed or injured Lesser. Is Lesser responding gratefully (even erotically) to his reprieve? Metcalfe’s casting of James Woods as the killer is a good choice, and Woods gives a powerful, searing performance. He does not compromise Panzram, or soften him. But the movie does, by withholding information. The real Panzram is well-documented in crime references, and he led quite a life: He was born in 1891, was in trouble with the law from the age of 8, burned down a reformatory when he was 14, and at 16 began a practice of sodomizing men at gunpoint (he counted more than 1,000). He burned churches in Montana, committed armed robberies in Oregon, worked in oil fields in South America and set oil rigs on fire for the hell of it, returned to the United States, stole $40,000 from the home of former President William Howard Taft, bought a yacht, hired 10 sailors as crew members, blew their brains out, dumped them in the sea, was arrested for burglary, escaped from prison again, went to Africa, sodomized and killed a 12-year-old, hired six porters to accompany him on a crocodile hunt, killed the porters and fed them to the crocodiles, and … you get the idea. He sang a little ditty on the gallows.

The movie is less than forthcoming about this life; its purposes are served by being vague about the details (although it does set the tally at 21 murders). It needs to humanize Panzram. Perhaps no one is completely irredeemable. But Panzram was a monster and prison was his destiny. If Lesser had sought out a different prisoner for his sympathy, “Killer” might have been more convincing. By choosing Panzram, Lesser places his own motives in a curious light: Was he attracted to evil? Was he excited by proximity to it, by his own invulnerability to such a dangerous man? Some people are.

I have just seen “Butterfly Kiss,” a British film about two women. One of them is an unhinged psychopath who stalks the motorways of Britain, killing people. The other is a dim young woman who feels sympathy for this lonely drifter. After she is sexually initiated by the killer (who is only the fourth person in her life to kiss her), she follows along on the trail of carnage, “always trying to find the good in her.” “Butterfly Kiss” is straightforward about three things that “Killer” doesn’t acknowledge: (1) It understands that sexual tension, whether overtly expressed or not, exists in such a relationship; (2) It understands that the “good” partner in such a pairing might be fulfilling deep and sick needs, and (3) It understands that evil on this scale is impenetrable to normal minds; that serial killers and those attracted to them are involved in a mystery that the rest of us will never really understand.

If you want to understand what’s going on in “Killer,” see “Butterfly Kiss.” It will deconstruct the earlier film for you, while itself remaining opaque and disturbing–as it should.