“I’ve looked all up and down these roads for someone to love me,” says Eunice, the tortured murderess and pilgrim whose story is told in “Butterfly Kiss.” Later she observes, “punishment is all I understand.” She is a gaunt, angry woman who stalks the roadsides of Britain, bursting into petrol stations to ask the women behind the counter, “Are you Judith?” Then she kills them.

But she doesn’t kill Miriam, the slow-witted, hard-of-hearing clerk who sees Eunice splashing herself with gasoline and walks out of the store and sits next to her on a concrete wall, and is kind to her. After they talk quietly, Eunice reaches out and kisses Miriam, who is from that moment completely dazzled by her power. “Mother, Auntie Kathy, a girl at swimming–and Eunice,” Miriam remembers. “Those are all the people who have kissed me.” The wounds of mental sickness, loneliness and need in “Butterfly Kiss” are so deep we can hardly watch. The women begin a journey across England, Eunice killing and Miriam mostly cleaning up after her, as we begin to understand how these two deeply scarred, incomplete personalities have somehow found the perfect fit. The writer, Frank Cottrell Boyce, and the director, Michael Winterbottom, show the relationship forming but allow it to be a mystery: Whatever draws these women together, logic is not relevant to it.

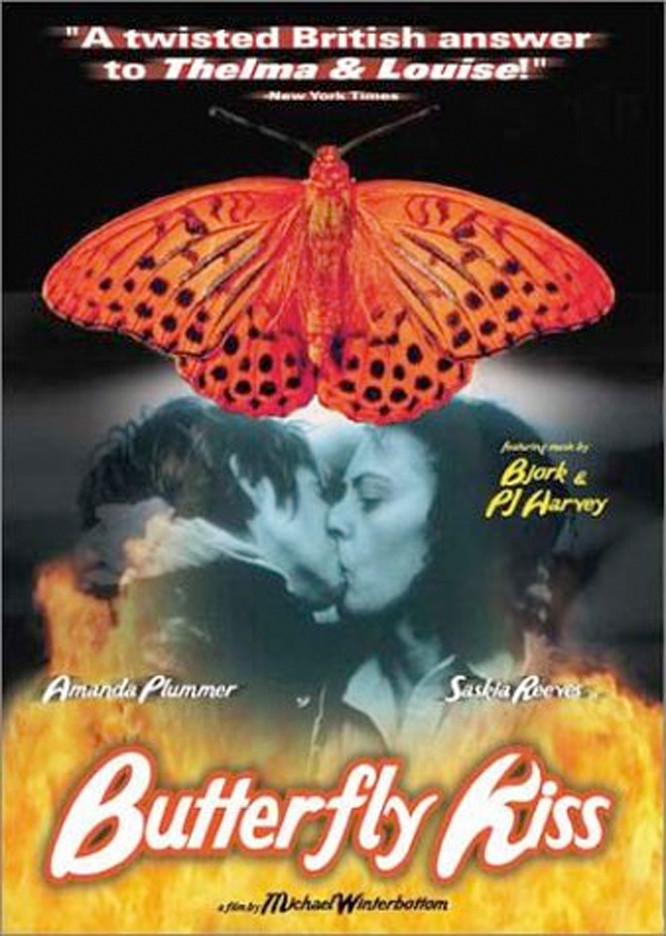

Miriam (Saskia Reeves), her long-sleeved sweater buttoned over her clerk’s smock, looks like an innocent, sentimental waif. Eunice (Amanda Plummer) looks hard-edged and worn by a lifetime of pain, and one of her small pleasures is to unbutton her blouse to show people that her gaunt body, covered with bruises, is wrapped in chains, her nipples pierced and linked. “She had 17 tattoos,” Miriam remembers, in a black-and-white video apparently made by the police at the end of it all. “And they all had a meaning.” Do the chains and piercings hurt? Yes, they do, Eunice says. She wants to be hurt. She is doing penance for her sins. At times she is articulate, wondering why nobody else will punish her. Is she so insignificant that God will let her murder people, and not even notice? The movie wisely never explains exactly who she is or where she comes from; this is not a case study but a sad parable.

Who is Judith, the woman she seeks? Some reviews have drawn insights from the biblical Judith, an avenger who beheaded an enemy of the Israelites. Has Eunice found Judith in the Bible, or been loved by her in some real or imagined past? Eunice never lets go of a packet of papers, wrapped in plastic, that contain all the “writings”–the documentation to support whatever madness her mind has thrown up as a bulwark against the world. Her quest for Judith defines her. The first day she meets Miriam, Eunice goes home with her, they make love, and Miriam is happy, one gathers, for the first time in her life. But the next morning the words “YOUR NOT JUDITH” are written in shaving cream on the mirror, and Eunice is gone.

Miriam chases after her down the highway, and finds her shortly after she’s murdered again. Miriam helps conceal the body. “I never stopped looking in her for the good,” she says in the videotape. Sometimes she seems dimly aware that there may not be very much good. Eunice gets into an argument about dolphins with a man who gives them a lift. He thinks they may be superior to humans. “We must be superior to the dolphins,” Eunice says, “since we kill the dolphins.” Later there is a frightening sequence when the two women, having stolen a car, give a lift to a homeless father and his daughter, and it seems that even the daughter will not be spared by Eunice. Miriam acts, here, to save the girl–but her loyalty to Eunice never falters.

The performances have a gravity about them that is unusual in the movies. Amanda Plummer (Honey Bunny in “Pulp Fiction”) plays Eunice with a fierce, if twisted, intelligence: She talks to herself, her eyes roam restlessly, but she always seems aware of exactly what she’s done, and is even able to analyze her own actions. Saskia Reeves (“Antonia and Jane”) plays Miriam with acceptance, warmth and sweetness, but little comprehension: She accepts all of Eunice’s horrifying crimes and scars and justifies them, driven by a complicated mix of need, sentimentality, incomprehension and sexual awakening. The movie’s weak point is in the black-and-white videotaped testimony, when Reeves lets Miriam seem more aware, more of a performer, than elsewhere in the film.

The names of the women are shortened in the movie, to the suggestive “Mi” and “Eu.” Can they be read as parts of a schizophrenic personality? Or is the story to be taken as it is told, as the record of a madwoman and a dim and trusting one who spend some bleak time together and are able to find a small measure of happiness? I don’t know. The movie doesn’t defend or glorify them; it simply shows them. How you respond to “Butterfly Kiss” depends on what you bring to it, and how much empathy you are willing to extend to these sad and horrifying women.