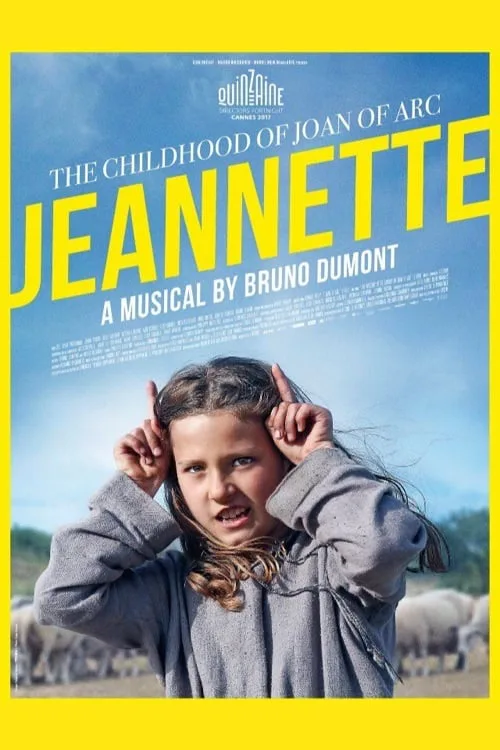

The high-concept premise of “Jeannette: The Childhood of Joan of Arc”—a French rock opera about Joan of Arc’s formative pre-war years—takes some getting used to. This is the kind of movie that gets stranger as you think about it. To get into this film, you have to find the emotional truth in the slightly awkward performances of non-professional child actors. You also have to get used to the idea of watching a film that follows, during its first half, an eight-year-old shepherdess (Lise Leplat Prudhomme) who head-bangs as she prays for an end to the Hundred Years’ War while heavy metal music plays. Imagine a cross between “Annie” and “Jesus Christ Superstar,” only with more speed metal. Now imagine a lot of long takes of sometimes merely adequate, sometimes sneakily brilliant performers doing simple dance steps or sing-talking reams of theatrical dialogue (adapted from Charles Peguy’s religious mystery play). Now picture beautifully shot, wind-swept beaches whose hills and never-ending sand dunes evoke an alien planet’s distant shore. That’s it, that’s “Jeannette.”

Please bear with me while I try to explain why writer/director Bruno Dumont (“Slack Bay,” “Lil Quinquin”) and his collaborators deserve the benefit of the doubt. Make up your minds later: just keep an open mind for now. Firstly, an apology: you could, theoretically, get distracted by any number of things in this film, like stiff acting, generic music, or blocky dialogue. These things do, admittedly, make it harder to focus on the essence and not the artifice of Dumont’s project. But that often seems to be the point of “Jeannette:” you have to grapple with the dual impulse to seriously consider and/or roll your eyes at the title heroine, a girl whose relationship with God is expressed through childish rhetorical questioning and child-like dancing and singing. She skips, jumps, and spins around whenever she’s not head-banging. And she asks God if He was right to send Christ down to Earth—”Could you have sent your son in vain? And could Jesus have died in vain?”—before admonishing other children her age: “Until war is killed, we have to work.” Her best friend Hauvette (Lucile Gauthier) tries to placate her: “You must be suffering to call God to account.” But this child cannot be shaken from her conviction that only a peaceful land can be saved.

Not much changes once Jeannette (Jeanne Voisin) and Hauvette (Victoria Lefebvre) turn 13, not in terms of their characters’ thoughts, nor in terms of the quality of their respective actresses’ performances. If anything, Dumont characteristically makes viewers hyper-aware that his actors are amateurs with limited range. But Prudhomme’s performance is exciting because it’s believably awkward, or maybe just unpredictable and a little brittle. You have to be able to believe that she’s an ordinary girl who won’t stop posing extraordinary questions, a child whose religious fervor is simultaneously unbelievable and impressive. To meet “Jeannette” at its level, you have to accept Dumont’s arch rules: you can only find the film as beautiful as it is strange if you first accept that there’s something a little alienating and proudly unreal about this film. You can never really suspend your disbelief because everything is a little rough on purpose. In fact, the only thing in “Jeannette” that is immediately—and therefore traditionally—impressive is its cinematography, and even that serves to enforce the idea that Jeannette is surrounded by inexplicable beauty.

Dumont typically refuses to give viewers a clear indication of how you are supposed to feel while watching young untrained actors pray and dance. He’s half-daring, half-inviting you to try to embrace his deliberately mystifying choices. So he emphasizes the look of conviction and the visible effort on his actors’ faces. And he gives them small, achievable movements that they can all credibly accomplish without calling too much attention to themselves, like shuffling their feet in unison, or head-banging with a stiff back. Each gesture is precise, but none of them give too much. Here is a real mystery play, one whose strength comes from the absurd certainty that at any moment, a serious prayer—or the silence that follows—could be interrupted by the intrusive bleating of a nearby sheep. Dumont may be the only filmmaker to auto-critique his own heroine via sheep noises (or sheep-song).

Finally, a confession: I wanted to write a review of “Jeannette” that made it more accessible, but realize now that I’ve made it sound even more unapproachable. That, too, is part of the process that many—but not all—viewers will go through when they watch this film. “Jeannette” is a challenging arthouse drama that has a slippery sense of humor and a whole lot of chutzpah. So no, I can’t fully explain why this film is so good. You really have to judge this one for yourself.