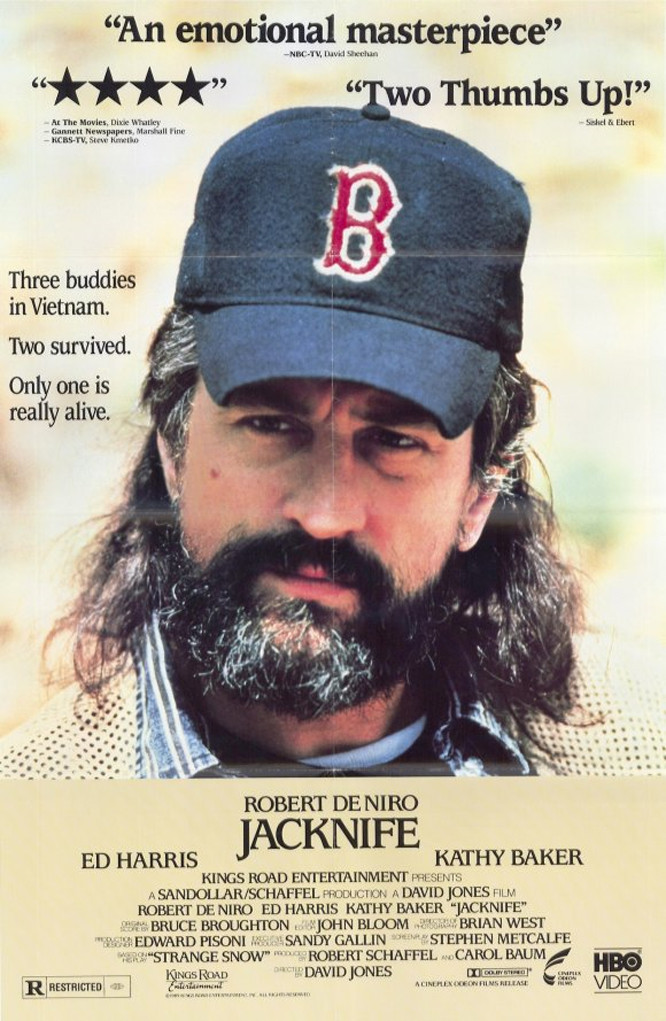

There is a sense in which “Jacknife” is a continuation of “The Deer Hunter,” the 1979 movie in which a group of friends from a working-class town in Pennsylvania went off to fight the war in Vietnam. “Jacknife” begins 15 years after the war is over and it takes place in a small town in Connecticut, but many of its shots and moods feel the same as in the earlier film, and the theme is the same, too: the idea that if your buddy gets left behind, you have to go back and get him.

The buddy who gets left behind this time is named Dave (Ed Harris). He doesn’t get left behind in Vietnam, though. He gets left behind in the America that he has returned to. While other veterans return to jobs or families or education, Dave returns to a life that is empty except for the booze and the cigarettes that keep him company in lonely bars.

Dave lives with his sister, Martha (Kathy Baker). She is a schoolteacher, in her 30s, and her life is on hold. Months pass into years in the house they inherited from their parents, where Martha’s role is to put Dave’s dinner on the table, do his laundry, change his sheets, give him money from time to time and accept him exactly as he is. Her problem is, until Dave’s life changes, hers cannot change, either. She is a classic case of an enabler; she’s a one-woman support system allowing Dave to continue to drink and throw his life away.

The buddy who comes back to rescue Dave is named Megs (Robert De Niro). He doesn’t have to come far – only across town. He turns up early one morning to remind Dave they have a date to go fishing together. It’s a long-standing date, with a lot of significance to it, but we don’t learn of the significance until later. Dave is in bed with a hangover, but Martha lets Megs in. He has never really noticed her before; maybe he’s never even seen her. Now he likes what he sees.

Megs is their deliverance. If he is successful, he will be able to get Dave moving again, help him break out of the vicious cycle of booze-hangover-booze. And if Dave becomes self-supporting, Martha will be free. Free for Megs, maybe. What Megs represents is change in a situation that has grown old with habit and stagnation.

There are not too many surprises in “Jacknife,” and not even the revelations in the flashbacks, the scenes showing what happened in the war, are really surprises. But this is not a movie of plot, it’s a movie of character. It’s about how these three people create a triangle of pain and possible healing. It’s not a buddy movie, where the woman looks on while the two guys work things out. It’s very much a triangle, in which a drunk has to learn to let go of his sister, a spinster has to learn to let go of her routine and a loner has to learn to let go of his detachment from life.

All three performances are right for the characters. De Niro makes a good choice for Megs because of the reserve he brings to the role. This is not a man doing something he wants to do, but something he has to do. Harris, staring at his cigarette, sitting hour after hour at the end of the bar, is able to project an unhappiness and frustration so deep that when he explodes, as he sometimes does, we are almost relieved. And Baker’s schoolteacher is not a drab wallflower who suddenly turns into a sexpot; she’s a calm, competent woman who has gotten trapped in something that her guilt will not let her escape from.

“Jacknife” has some effective scenes that take place in a veteran’s encounter group, where the lesson is that life goes on, and that today cannot be lived out in painful memories of the past. That’s the same message Megs has for Dave. To a degree, this lesson is both familiar and predictable. “Jacknife” redeems it in the specifics of the performances. De Niro, Harris and Baker seem to be oblivious to the “message,” and lose themselves in the personalities of their characters. And so the movie works.