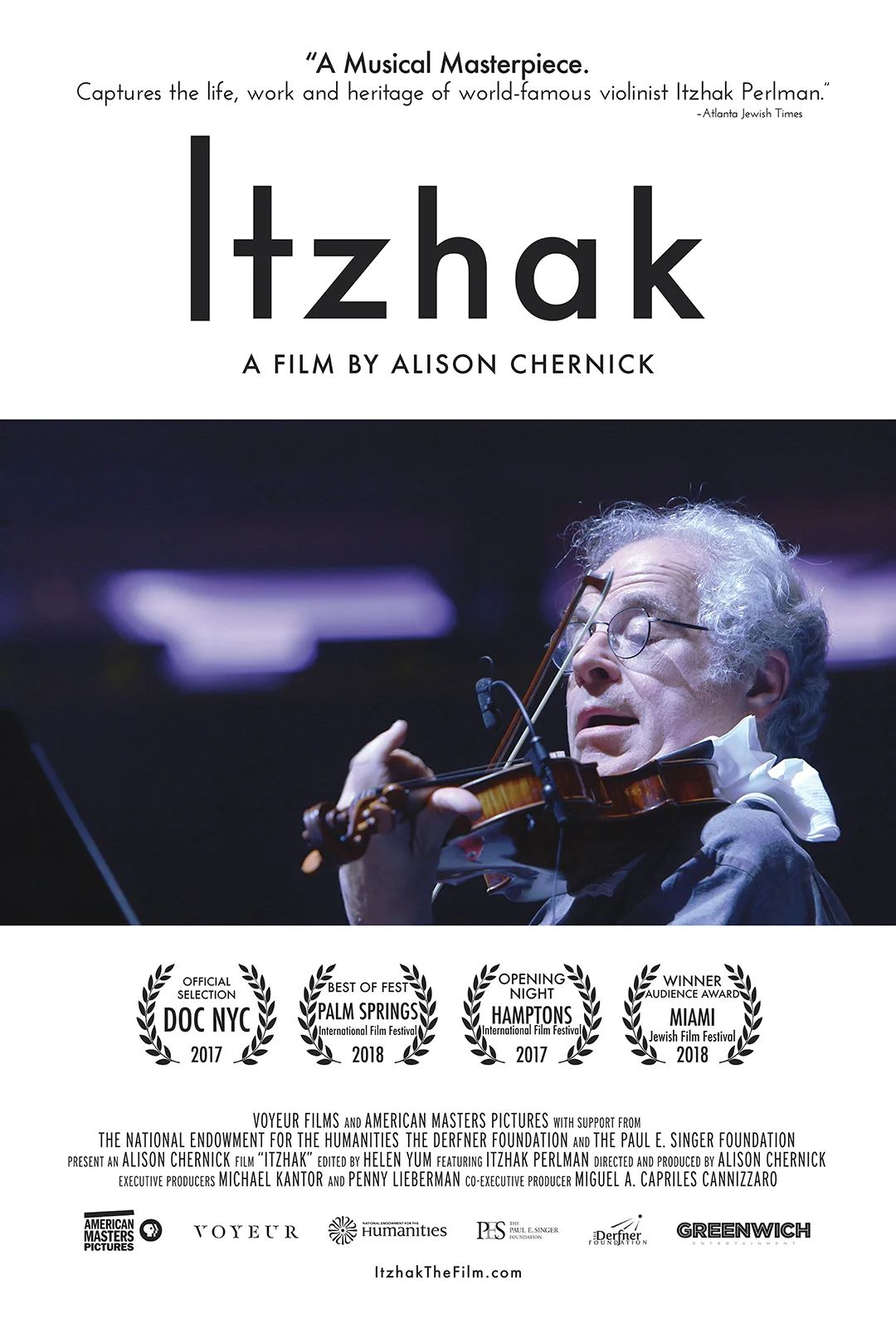

“Itzhak” is a joyous film about a joyous man. Directed by Alison Chernick, it’s a compact and immensely likable look at virtuoso violinist Itzhak Perlman. It’s less concerned with covering the totality of his life than evoking his life force, which is good-humored, earthy and inspiring.

Because of its brevity, as well as its decision to show the subject existing in the moment rather than convene a bunch of talking heads or a narrator to discuss what his life and work have meant, “Itzhak” is best appreciated by people who know a little bit about Perlman already—or who are OK with a film that’s more of a pencil sketch on a cocktail napkin than a oil painting with an ornate frame that’s intended to hang in a portrait gallery. This is a work in the tradition of fly-on-the-wall celebrity portraits from the 1960s and ’70s, like the classic Bob Dylan documentary “Don't Look Back.” It hangs out with Perlman, his wife Toby, his extended family and some of his colleagues, and watches them interact.

As accomplished as the film is at a craft level, there’s no denying that much of its impact comes from having chosen Perlman as its subject. He’s a fascinating man who’s lived a dramatic life, starting at age four, when he contracted polio that impaired his mobility but did not stop him from becoming one of the world’s most-honored instrumentalists.

Some archival footage is deftly woven into the present-day material. This includes snippets of Perlman performing in different decades, pieces of a 1993 interview with his beloved mentor Dorothy Delay (who called him “Sugarplum” and asked him brain-teasing questions like, “What’s your concept of G-sharp?”), and a clip of a 13-year old Perlman performing on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” Of the latter, Perlman acknowledges that, as talented as he clearly was, even at that tender age, he was booked because of his heroic handicapped-kid-overcomes-adversity story—and that this particular aspect of his narrative has guided many of his choices as a public figure and philanthropist.

The Perlmans’ marriage is the foundation of the movie. Their interaction is a model of a fully functioning, long-lasting union based on mutual intellectual respect as well as affection. They’ve been together over 50 years and still enjoy each other’s company. Toby is his biggest fan as well as advocate. “When I hear that sound, when I hear that playing,” Toby says of Itzhak’s musicianship, “It’s like breathing. It’s like being alive.” But she’s also his toughest critic, and has no compunction about telling him that a performance that dazzled thousands wasn’t up to his highest standards.

From the opening scene of Perlman riding an Amigo scooter through the passageways of Citi Field en route to play “The Star-Spangled Banner” before a New York Mets game, through late sections capturing his performance of John Williams’s score for “Schindler's List” (for which he served as lead violinist), the film confirms Perlman’s popular touch. He’s a great raconteur and listener, so charismatic that he naturally claims the spotlight wherever he is, yet one can’t help being struck by his approachable demeanor. Whether conducting an orchestra, sitting in with Billy Joel, dining with friends and family around a large table, or accepting an award, his accomplishments and aura never precede him, nor do they defensively cloak him in “greatness” or separate him from the supposed rabble. He seems delighted to be a part of the world he moves through, and that his art has made more bearable. He seems particularly amused by small children and pets.

The filmmaking itself displays mastery in the spirit of its subject. There’s never a doubt that you’re in the hands of craftspeople operating at the peak of their powers, even as each choice serves the work. Helen Yum’s editing is superb. It displays a rare sense of how to cut musical performances and dialogue together in a way that preserves the continuity of the music while favoring the forward motion of the story. The editing of the non-musical scenes is equally impressive. There are a number of moments where the cutting of conversations attains a musicality of its own, evoking instruments in an orchestra taking cues from one another as well as the conductor.

A student in a class being guest-taught by Perlman astutely observes that, in musical performance, it’s not enough just to hit the right note at the right moment: one must devote equal thought and care to entering and exiting the note, because it’s the decision of when to get in and out, and how, that shapes emotion. She could be describing this documentary, a musical film about music and life.