I’ve seen “Ismael’s Ghosts” twice, and both times I got the feeling that I was missing something. The film feels very personal, as if writer/director Arnaud Desplechin were sorting out his thoughts, processes and demons onscreen. This notion became even more apparent when, after initially playing at Cannes in a shorter cut, Desplechin felt compelled to present a longer, slightly reworked director’s cut for general release. I have not seen the Cannes cut, but I am told that this version is richer, deeper and more introspective. Regardless of the cut, one can more deeply understand “Ismael’s Ghosts” if one goes into it armed with firsthand knowledge of the director’s oeuvre.

This presented a slight dilemma for me, as I am not very familiar with Arnaud Desplechin. I’ve seen only two of his other works, neither of which lent much insight into cracking “Ismael’s Ghosts.” As your humble reviewer I felt a bit torn; on the one hand, there’s the question of how much did I know about the larger body of work to which this film occasionally refers, and when did I know it. On the other hand, this is a review, not a dissertation. My job is to assess this film, not its prerequisites. When you buy your ticket to “Ismael’s Ghosts,” all you’re getting is “Ismael’s Ghosts.” I’m not sure if my rating would be any different if I were an expert on Desplechin. In fact, I think it might have been lower, because being in the dark gave me a better connection to what I believe the director wanted me to feel.

“Ismael’s Ghosts” is about things that are missing, whether it’s a lost love or a creative idea perilously out of one’s reach due to writer’s block. Both of these present problems for director Ismael Vuillard (Mathieu Amalric). He is in the middle of creating his latest movie, a violent yarn about a spy named Ivan (Louis Garrel, whose father Phillipe also makes films that often reference one another). Ivan’s adventures occasionally take over the narrative—we see footage Ismael has shot as well as half-formed ideas that exist only in his head. Desplechin drops these moments in without warning, initially undercutting our grasp on the narrative. Ivan’s world is clearly not real, but it overlaps with Ismael’s reality, blurring the lines on what we should take at face value. We become purposefully aware that we are watching a movie.

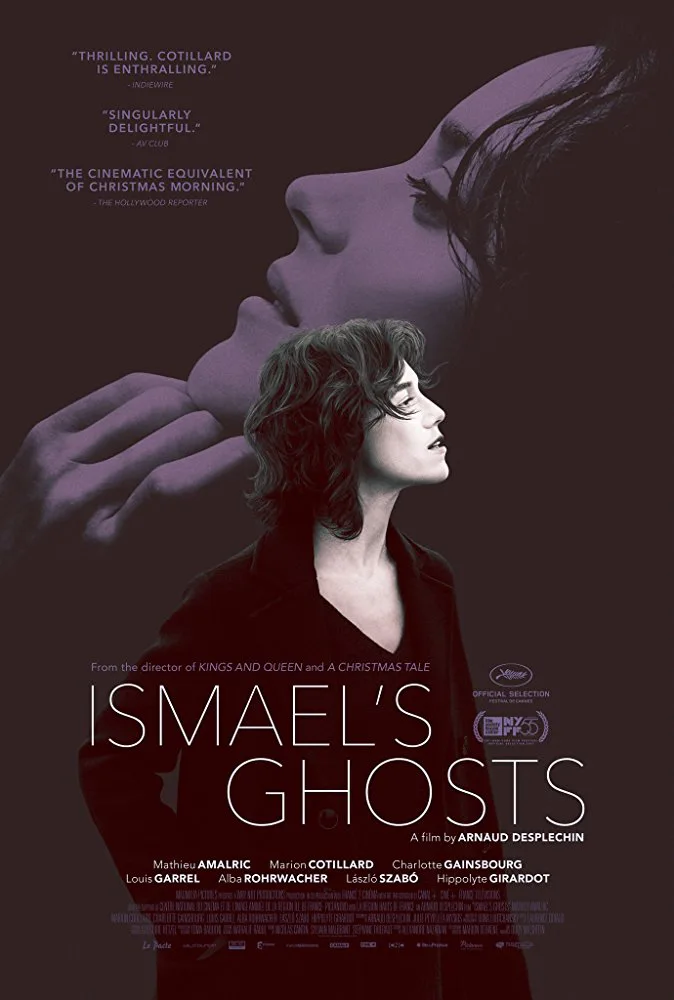

Once Desplechin has us focused on the theatricality of “Ismael’s Ghosts” he presents the aforementioned missing lost love. Ismael’s wife, Carlotta (Marion Cotillard, very good here), disappeared without warning twenty years ago. Since then, her mystery has haunted Ismael and driven her aging father, Henri (László Szabó) somewhat mad. Ismael maintains a relationship with Henri, presumably because the shared trauma of Carlotta’s disappearance forever binds them. Ismael has even declared Carlotta dead, filing paperwork in that regard with the records bureau. Henri blames Ismael for Carlotta’s absence, thinking, as most fathers would, that his daughter was an angel who could do no wrong. Unlike Ismael, he is blissfully unaware of his daughter’s constant philandering during her marriage.

When Carlotta shows up, we think the movie might be playing tricks on us. Is this a figment of Ismael’s imagination? Then she speaks with Sylvia (Charlotte Gainsbourg), Ismael’s current girlfriend. Sylvia recognizes her from the large painting hanging in Ismael’s house, a painting that evokes old studio system-era gothic romantic mysteries like “Laura” and “Rebecca.” Carlotta nonchalantly tells Sylvia she has come back to claim what is rightfully hers, and plans to do so while completely ignoring the 20 years she has been gone.

Sylvia brings Carlotta back to Ismael’s house, where her presence unleashes all manner of emotional and psychological hell. Ismael runs the gamut of emotions from anger to confusion to lust. Henri starts to doubt his own sanity, thinking his daughter is a ghost he’d rather not see in the flesh. To him, she’s a portent of his own demise. To Ismael, she’s a vengeful specter reminding him of what could have been.

It’s here where “Ismael’s Ghosts” becomes a completely cinematic contraption, fragmenting itself into several different threads all emanating from Ismael’s tenuous grasp on events. Desplechin uses these elements to make a playful commentary on the creative process. Ismael disappears from the set, holing himself up at his beach house while struggling with how to finish the script for his Ivan spy movie. Ivan’s movie plays out before us, showing us the corners into which Ismael defiantly paints himself. Then another Ivan shows up to show where Ismael got the inspiration for his hero. Ismael’s angry producer also shows up at an inopportune moment, only to be accidentally shot in the arm by Ismael. “What director doesn’t dream of shooting his aggravating producer?” Desplechin seems to gleefully ask us.

And so it goes. By the time Sylvia breaks the fourth wall to speak directly to us, you have either surrendered to the game or been completely flustered by it. Your mileage may vary, but I often like to be left to my own devices by a movie that is willing to tell me enough information to be dangerous but not enough information to be sure. This is a film about things that are missing, and the fact that I felt I too was missing something while watching it seems wholly appropriate. After all, one should feel a little haunted by a film with ghost in the title, n’est-ce pas?