“Indochine” intends to be the French “Gone With The Wind,” a story of romance and separation, told against the backdrop of a ruinous war. The French, of course, have their own ways of approaching such epic topics, and this movie is heavier on boudoirs and chic, lighter on bluster and battle, than our American classic.

It is also curiously inconclusive, leading up to a final meeting that never takes place.

There are many good things in this film, not least the sense of time and place: French Indochina, later Vietnam, from the years of colonial calm to the days when the French withdrew and the beautiful country became an American trauma. This period is largely seen through the eyes of the owner of a French plantation (Catherine Deneuve), her adopted Vietnamese daughter (Linh Dan Pham) and the daughter’s son, who is raised mostly in France by Deneuve after the mother becomes a revolutionary.

There is always something bittersweet and decadent about the dying days of colonial regimes; the old customs have outlasted their times, and yet people go through the motions, their manners and folkways reflecting a certain stubborn pride. They are yesterday’s people, not ready to admit it. You get that feeling in films like “White Mischief” and “A Passage to India,” and you get it here, too, as the Deneuve character strides fearlessly among her plantation workers, who may, for all she knows, be communists preparing an uprising. She is protected by the invisible shield of decades of French rule.

Her society is a decadent one. She looks cool and elegant, and is dressed in understated tropical chic, but from time to time she has a Chinese retainer prepare her an opium pipe, and she is not above a sudden rush of passion with a handsome young French Naval officer (Vincent Perez). He, alas, then falls in love with Deneuve’s beautiful young adopted daughter, and betrays the values of his officer class to embrace the rising tide of anticolonial rebellion.

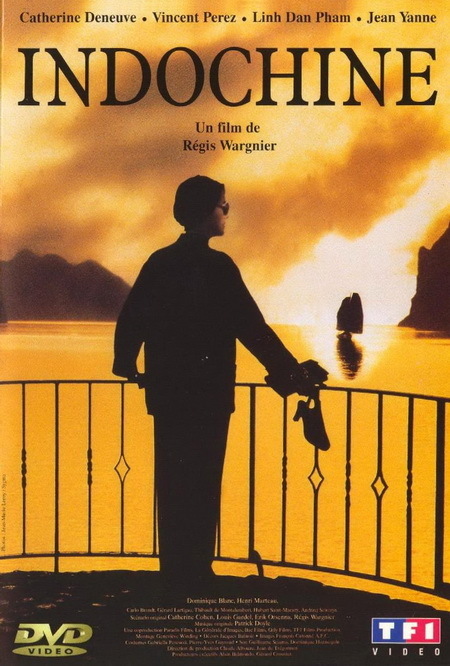

The photography is the star of this movie. As the two young lovers run away, hoping to hide themselves in the countless islands of a secret lake, a vast long shot shows their boat as a speck surrounded by magnificent landscape. Many other shots show an architecture in harmony with the land and the climate, the outdoors sensed from indoors, the walls and windows slatted or curtained so that all life seems partly exhibitionism.

Through this film, Deneuve drifts like an angel. She is as beautiful as ever, in the role of a lifetime – she spans decades, yet never ages, and the problem is not to make her seem young for the early scenes but old enough for the later ones. Her serenity in the face of crisis is perhaps too perfect; a grittier, earthier woman might have connected better with the realities of the country. Here we get Scarlett in her gowns but not the Scarlett who grubs for potatoes.

The screenplay does the film no favors. It is long and discursive and not very satisfying. After a grand melodrama like this, we expect an ending more satisfactory than the epilogue in Geneva, with Deneuve and her grandson awaiting the daughter and the Vietnamese revolutionary committee. Of course, the story of Vietnam did not end at that point, and so perhaps the story of this movie cannot either.

“Indochine” is an ambitious, gorgeous missed opportunity – too slow, too long, too composed. It is not a successful film, and yet there is so much good in it that perhaps it’s worth seeing anyway.

The beauty, the photography, the impact of the scenes shot on location in Vietnam, are all striking. But the people seem to drift and waver in their focus. The film seems to suggest that the French still do not quite understand what happened to them in Vietnam. Well, they’re not alone.