What strange confusion besets Jean-Luc Godard? He stumbles through the wreckage of this film like a baffled Lear, seeking to exercise power that is no longer his. “In Praise of Love” plays like an attempt to reconstruct an ideal film that might once have existed in his mind, but is there no more.

Yes, I praised the film in an article from the 2001 Cannes Film Festival, but have now seen it again, and no longer agree with those words. Seeing Godard’s usual trademarks and preoccupations, I called it “a bittersweet summation of one of the key careers in modern cinema,” and so it is, but I no longer think it is a successful one.

Godard was the colossus of the French New Wave. His films helped invent modern cinema. They were bold, unconventional, convincing. To see “Breathless,” “My Life to Live” or “Weekend” is to be struck by a powerful and original mind. In the late 1960s he entered his Maoist period, making a group of films (“Wind from the East,” “Vladimir and Rosa,” “Pravda”) that were ideologically silly but still stylistically intriguing; those films (I learn from Milos Stehlik of Facets Cinematheque, who has tried to find them) have apparently been suppressed by their maker.

Then, after a near-fatal traffic accident, came the Godard who turned away from the theatrical cinema and made impenetrable videos. In recent years have come films both successful (“Hail, Mary”) and not, and now a film like “In Praise of Love,” which in style and tone looks like he is trying to return to his early films but has lost the way.

Perhaps at Cannes I was responding to memories of Godard’s greatness. He has always been fascinated with typography, with naming the sections of his films and treating words like objects (he once had his Maoist heroes barricade themselves behind a wall of Little Red Books). Here he repeatedly uses intertitles, and while as a device it is good to see again, the actual words, reflected on, have little connection to the scenes they separate.

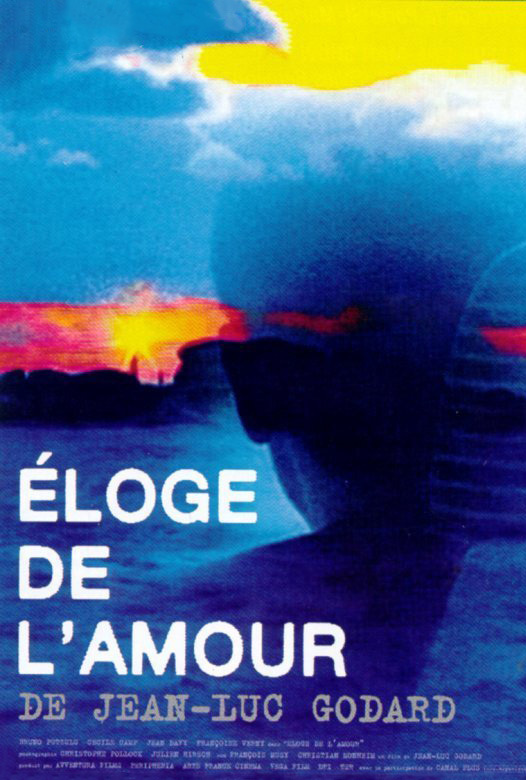

He wants to remind us “In Praise of Love” is self-consciously a movie: He uses not only the section titles, but offscreen interrogators, polemical statements, narrative confusion, a split between the black and white of the first half and the saturated video color of the second. What he lacks is a port of entry for the viewer. Defenses of the film are tortured rhetorical exercises in which critics assemble Godard’s materials and try to paraphrase them to make sense. Few ordinary audience members, however experienced, can hope to emerge from this film with a coherent view of what Godard was attempting.

If you agree with Noam Chomsky, you will have the feeling that you would agree with this film if only you could understand it. Godard’s anti-Americanism is familiar by now, but has spun off into flywheel territory. What are we to make of the long dialogue attempting to prove that the United States of America is a country without a name? Yes, he is right that there are both North and South Americas. Yes, Brazil has united states. Yes, Mexico has states and is in North America. Therefore, we have no name. This is the kind of tiresome language game schoolchildren play.

It is also painful to see him attack Hollywood as worthless and without history, when (as Charles Taylor points out on Salon.com), Godard was one of those who taught us about our film history; with his fellow New Wavers, he resurrected film noir, named it, celebrated it, even gave its directors bit parts in his films. Now that history (his as well as ours) has disappeared from his mind.

His attacks on Steven Spielberg are painful and unfair. Some of the fragments of his film involve a Spielberg company trying to buy the memories of Holocaust survivors for a Hollywood film (it will star, we learn, Juliette Binoche, who appeared in “Hail Mary” but has now apparently gone over to the dark side). Elsewhere in the film he accuses Spielberg of having made millions from “Schindler's List” while Mrs. Schindler lives in Argentina in poverty. One muses: (1) Has Godard, having also used her, sent her any money? (2) Has Godard or any other director living or dead done more than Spielberg, with his Holocaust Project, to honor and preserve the memories of the survivors? (3) Has Godard so lost the ability to go to the movies that, having once loved the works of Samuel Fuller and Nicholas Ray, he cannot view a Spielberg film except through a prism of anger? Critics are often asked if they ever change their minds about a movie. I hope we can grow and learn. I do not “review” films seen at festivals, but “report” on them–because in the hothouse atmosphere of seeing three to five films a day, most of them important, one cannot always step back and catch a breath. At Cannes I saw the surface of “In Praise of Love,” remembered Godard’s early work, and was cheered by the film. After a second viewing, looking beneath the surface, I see so little there: It is all remembered rote work, used to conceal old tricks, facile name-calling, the loss of hope, and emptiness.