In the final decades of apartheid in South Africa, few observers thought power would change hands in the country without a bloody war. But white rule gave way peacefully to the Nelson Mandela government, and Mandela and F.W. de Klerk, the departing prime minister, shared the Nobel Peace Prize.

That miracle nevertheless left a nation scarred by decades of violence — not only of whites against blacks, although that predominated. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the inspiration of Mandela, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and other leaders in the new society, found a way to deal with those wounds without resorting to the endless cycle of bloody revenge seen in Northern Ireland, Bosnia and elsewhere. The commission made a simple offer: Appear before a public tribunal, confess exactly what you did, convince us you were acting under orders, make an apology we can believe, and we will move on from there.

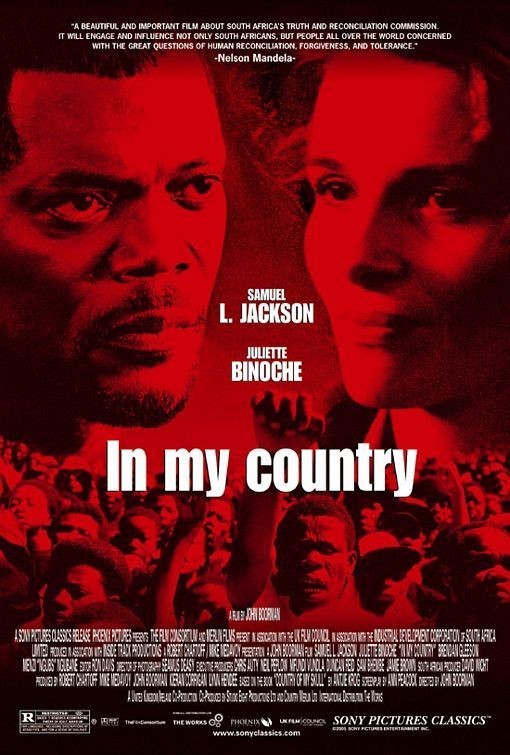

John Boorman’s “In My Country” is set at the time of the commission’s hearings, and stars Samuel L. Jackson as Langston Whitfield, a Washington Post reporter covering the story, and Juliette Binoche as Anna Malan, a white Afrikaaner who is doing daily broadcasts for the South African Broadcasting Company. As the commission and its caravan of press and support staff travel rural areas, Whitfield and Malan find themselves in disagreement about the Commission, but strongly attracted to each other.

I confess I walked into the film with strong feelings. I’ve spent a good deal of time in South Africa, including a year at the University of Cape Town. I had the opportunity to discuss the commission with Archbishop Tutu. I believe the transitional period in South Africa is a model for an enlightened and humane reconciliation with past evils. “In My Country” shows the process at work and argues in its favor, and I tended to approve of it just on that basis.

Yet there is something not quite right about the film itself. The affair between Whitfield and Malan seems arbitrary, more like two writers having sex on the campaign trail than like two people involved in a romance that would be important to them. Both are married, and neither wants to leave their marriage, although perhaps in the grip of infatuation they waver. Although apartheid imposed criminal penalties for interracial sex under its “Immorality Act,” that does not necessarily mean that interracial sex has to be in the foreground of a movie about Truth and Reconciliation — particularly if it’s an affair involving a visiting foreigner. There seems something too calculated about the movie’s pairing up of the political and the personal.

There is another unconvincing aspect: Whitfield, the Washington Post reporter, is not convinced that the commission hearings are useful or just. He thinks the wrongdoers are getting off too easy and says so at press conferences, becoming an advocate and making no attempt to seem objective. It is up to Anna Malan (and the plot) to persuade him otherwise. There is a certain poetic irony in an Afrikaaner convincing an African American that Mandela’s new South Africa is on the right track, but isn’t it more of a fictional device than a likely scenario?

A scene where Malan brings Whitfield home to her family farm seems contrived because we are not sure what Anna hopes to accomplish with it, and at the end of the scene that is still unclear. True, during the visit we are able to see white unease about the transfer of power (“They’re not our police anymore. It’s not our country anymore”). But the romance adds complications that are essentially a distraction from the main line of the story.

The movie, written by Ann Peacock, is based on a book by Antjie Krog, whose own radio and newspaper reports of the hearings inspired the character of Anna Malan. It has scenes of undeniable power. Many of them involve a character named de Jager (Brendan Gleeson), a South African cop with a zeal for torture and murder that went far beyond his job requirements. Whitfield’s encounter with de Jager is tense and strongly played. There are also moments of real emotion during the testimony from a parade of whites (and one black) seeking forgiveness.

As it happens, I’ve seen another film on the same subject. That is “Red Dust,” a selection at Toronto 2004, starring Hilary Swank as a New York attorney who returns to her native South Africa to represent a political activist (Chiwetel Ejiofor) in the amnesty hearing for his torturer (James Bartlett). Bartlett’s character serves something of the same function as Gleeson’s in the other film, but all of the characters and their stories are more complex and contradictory, reflecting their turbulent times.