There is a shot near the beginning of “I Am Cuba” that is one of the most astonishing I have ever seen. Reflect that it was made in 1964, long before the days of lightweight cameras and Steadicams, and the shot is almost impossible to explain.

It begins on a rooftop deck of a luxury hotel in pre-Castro Havana. A beauty pageant is in progress. The camera sinuously winds its way past bathing beauties, and then moves over the edge of the deck and descends vertically, apparently floating, down three or four stories to another deck, this one with a swimming pool. The camera approaches a bar, and then follows a waitress as she delivers a drink to some tourists, after which one of the tourists stands up and walks into the pool – and the camera follows her, so that the shot ends with the camera actually underwater.

As nearly as I can tell, this is all done in one unbroken take. How it was done, I have no idea. It is interesting not only for its technical skill, but also because it betrays a certain interest in la dolce vita that is not entirely in keeping with the movie’s revolutionary, agitprop stance.

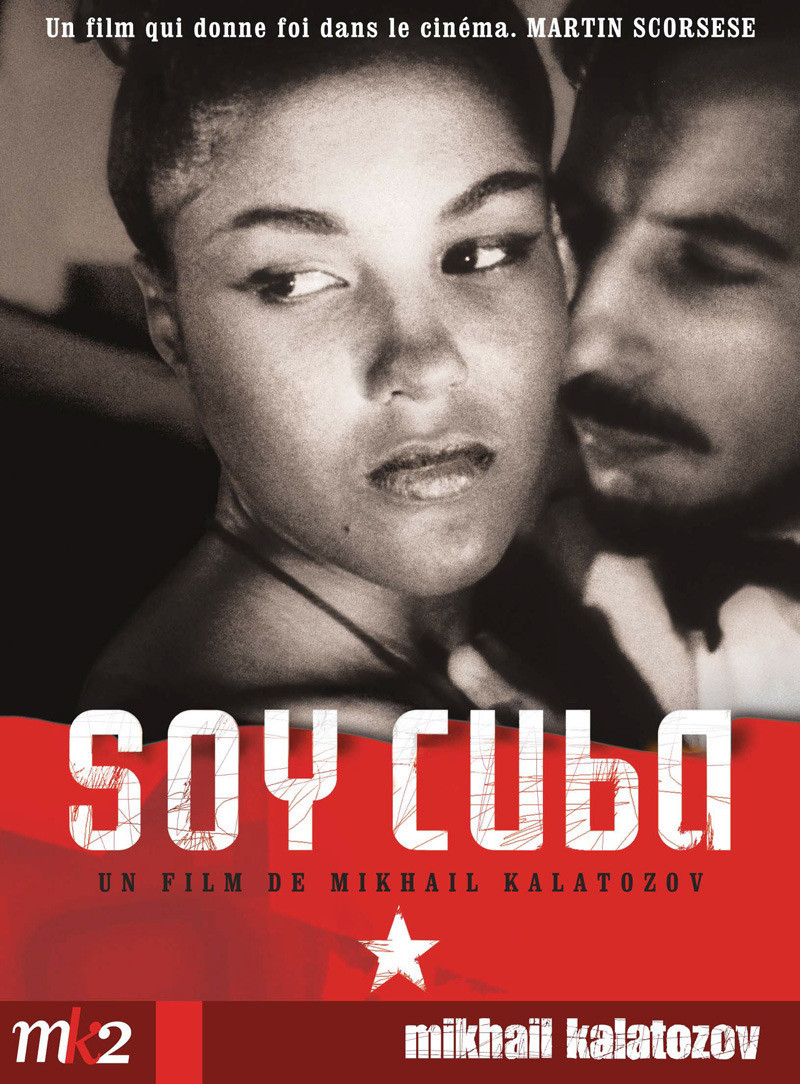

“I Am Cuba” is an anti-American propaganda film, made as a Cuban-Soviet co-production, that has been snatched from oblivion, restored, and released in the United States as a presentation of Martin Scorsese and Francis Coppola. Since the film’s prediction of a brave new world under Fidel Castro has not resulted in a utopia for Cubans, who suffer under one of the world’s most dismal bureaucracies, the film today seems naive and dated – but fascinating.

The Soviets fielded a first-class team of advisers to help in the production. The script was co-authored by Yevgeny Yevtushenko, then the USSR’s poetic superstar, and Enrique Pineda Barnet, a Cuban novelist. It was directed by the veteran Russian filmmaker Mikhail Kalatozov, then 61, whose “The Cranes are Flying” (1957) had won the Palme d’Or at Cannes a few years earlier. That film featured spectacular camera techniques, but they are upstaged by his opener in “I Am Cuba” and by some of the other sequences, which owe much to Fellini’s influential “La Dolce Vita” (1960).

The movie is didactic in the best tradition of Socialist Realism. First, it shows Cuba groaning under the yoke of Yankee imperialism. Then it shows resistance, by brave farmers and heroic students. Finally, there is the appearance of a great revolutionary hero, a bearded man of the people who fights in the hills, is sheltered by peasants and represents Fidel Castro.

The anti- American content is handled in a nightclub scene, where gum-chewing Yankees ogle the prostitutes, and one amateur anthropologist announces, “I’d like to see where these women live.” Against her better judgment, a girl takes the man home to her shack, where he offends her by offering to buy her crucifix. Worse, they are discovered by her fiancé, a humble fruit peddler, who believed she was a virgin. This sequence, heavy on schmaltz, nevertheless has a real poignancy.

The film is not done with Americans. We see drunken American sailors chasing women through the streets, and follow the story of a hard-working peasant whose lands and home are snatched by the United Fruit Co. Rather than surrender his cane fields, he sets them afire.

Then we see the resistance: students agitating the change, including one who mimeographs propaganda pamphlets and then is shot dead, his body covered in a snow of the revolutionary sheets.

Kalatozov’s fancy shots are not limited to the opening extravaganza. There is a sequence later in the film that begins with the streets filling with demonstrators and then seemingly floats, in an unbroken take, into a high-rise cigar factory. His technique seems somewhat at odds with his purpose (you won’t find shots like these in Italian neo-realism), but then the movie itself alternates between lyricism and propaganda. Along with the scenes of evil Yankees and brave Castroites, there are astonishing helicopter shots of Cuban landscapes, and poetry and prose are read on the soundtrack (Columbus is quoted: “This is the most beautiful land ever seen by human eyes”).

The movie, now in limited distribution before a video release, is of course dated in its politics. Even its depravities and imperialist Yankee misbehavior seem quaint. But as an example of lyrical black and white filmmaking, it is still stunning. If you see it, try to figure out how the camera floated down that wall.