The business of crime is as much business as crime, as Martin Scorsese demonstrated in “Casino” by centering his story on a gangster who was essentially an accountant and oddsmaker. Now Bill Duke’s “Hoodlum” looks into the way the Mafia muscled into the black-run numbers racket in Harlem in the 1930s; this is a “gangster movie” in a sense, but it is also about free enterprise, and about how, as the hero says when asked why he didn’t go into medicine or law, “I’m a colored man and white folks left me crime.” Of course that is not quite the whole story, but by the time Bumpy Johnson (Laurence Fishburne) says it, it’s true of him: He’s a smart ex-con, returned to the streets of Harlem during its pre-war renaissance, when music, arts and commerce flourished along with the numbers game. He hooks up with old friends, including Illinois Gordon (Chi McBride), who masks his feelings with jokes and introduces him to a social worker Francine Hughes (Vanessa L. Williams).

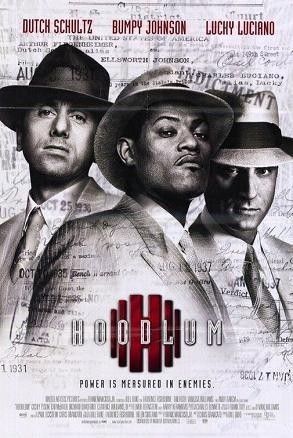

Francine sees the good in Bumpy, and encourages him to make something of himself, but Bumpy defends his career choice: “The numbers provide jobs for over 2,000 colored folks right here in Harlem alone. It’s the only home-grown business we got.” The game is run by Stephanie St. Clair (Cicely Tyson), known as the Queen of Numbers. She’s from the islands, elegant, competitive. She takes on Bumpy as her lieutenant. The mob has up until now let Harlem run its own rackets, but Dutch Schultz (Tim Roth) moves in, trying to take over the numbers. His nominal boss is the powerful Lucky Luciano (Andy Garcia), who disapproves of Schultz because of the way he dresses (“You got mustard on your suit”), and is inclined to stand back and see what happens. He doesn’t mind if Schultz takes over Harlem, but is prepared to do business with the Queen and Bumpy if that’s the way things work out.

One thing that has kept the Mafia from attaining more power in the United States is that it has a tendency to murder its most ambitious members; the guys who keep a low profile may survive, but are not leadership material. Imagine a modern corporation run along the same lines. Bumpy is the far-sighted strategist who sees that it’s better to talk than fight; Dutch is the thug who itches to start shooting.

This is Bill Duke’s second period film set in Harlem, after “A Rage in Harlem” (1991). He likes the clothes, the cars, the intrigue. (In both films, interestingly, he didn’t film in Harlem, finding better period locations in Cincinnati for “Rage” and Chicago for “Hoodlum.”) He builds up to some effective set-pieces, including a massacre that interrupts a trip to the opera; in the payoff, Bumpy and the Queen listen to an aria while he has blood on his shirt.

The film’s argument is that the policy racket, like many legitimate home-grown black businesses, was appropriated by whites when it became too powerful. The streets of inner-city America are lined with shuttered storefronts while their former customers line up at Wal-Mart. And, yes, there is an element of racism involved: When I was growing up in Champaign-Urbana in the 1940s and 1950s, the richest black man in town was said to be the local numbers czar. Whites had no problem with the numbers (some played), but they couldn’t stop talking about how a black man could make all that money.

Duke and his screenwriter, Chris Brancato, don’t make “Hoodlum” into a violent action film, though it has its bloody shoot-outs, but into more of a character study. Schultz is painted as a crude braggart, Lucky Luciano is suave and insightful, and the most intriguing figure among the white characters is crime fighter Thomas Dewey, who ran for president in 1948 as a reformer, but is portrayed here, in scenes sure to be questioned in many quarters, as a corrupt grafter. (Schultz observes that he is paying off Dewey at the same time the famed prosecutor is getting headlines for trying to put him in jail.) Bumpy Johnson is played by Fishburne as someone who could have had a legit career, and he’s torn when Francine, the social worker, cools toward him because of his occupation. Illinois Gordon, his best friend, also asks hard and idealistic questions, especially after a funeral. By creating these two characters, the screenplay gives Bumpy somewhere to turn and someone to talk to, so he isn’t limited to action scenes. As Stephanie St. Clair, Cicely Tyson models her character on real women of the period, who were tough, independent, and used men without caving in to them.

“Hoodlum” is being marketed as a violent action picture, and in a sense, it is. But Duke has made a historical drama as much as a thriller, and his characters reflect a time when Harlem seemed poised on the brink of better things, and the despair of the postwar years was not easily seen on its prosperous streets. Was the policy game all that bad? Sure, the odds were stiff, but a couple of times a week, someone had to win. These days, it’s called the lottery.