Don’t expect to go into writer/director Alex Ross Perry’s sixth feature “Her Smell,” a suffocating plunge into a female musician’s deteriorating world, and come out with calm instead of chaos. Not that the former aftertaste had ever been the kind of trace left by any of Perry’s previous films. From “Listen Up Philip” to “Golden Exits,” his cinema has always been mostly concerned with Woody Allen-esque anti-heroes and misbehavers from privilege, with their sympathies openly (and sometimes, sneakily) aligned with males even when the films themselves were female-centric.

But with the disorderly “Her Smell,” the filmmaker seems to have taken his hectic preoccupations into a whole new dimension. Even the gritty, sweaty, red-lit spaces of Gaspar Noé’s recently released “Climax” might not quite prepare you for this fast and snippy pandemonium. Through the fragmented story of a larger-than-life but past-her-prime ‘90s punk-rock star who’s fallen victim to addiction—Courtney Love comparisons are certainly apt here—Perry stuffs “Her Smell” with an alarming dose of physical and emotional suffering. So much that many will find going through this turmoil unscathed virtually impossible.

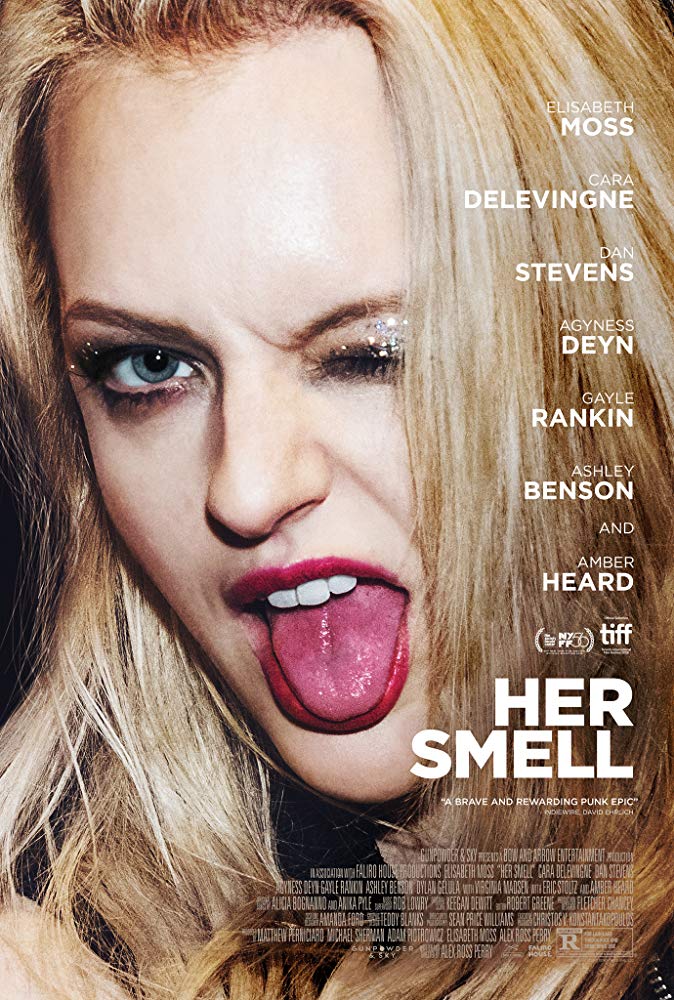

This last sentence is both a mixed response to what Perry achieves in “Her Smell”—sure, he succeeds at making you feel the hurt of his aging star named Becky Something (Elisabeth Moss, never more pained or maniacal), though at what cost?—and a fair warning for the viewer. In five distinct and frantically escalating narrative acts spread across nearly a decade, Becky goes down the deep end relentlessly, in front of anyone who’s ever cared for her—fellow Something She band-members Ali (Gayle Rankin) and Mari (Agyness Deyn), the now-struggling record executive Howard (Eric Stoltz), her powerless mother who once financially relied on Becky (Virginia Madsen), her fed-up yet well-meaning musician ex Danny (Dan Stevens), her young daughter Tama (Daisy Pugh-Weiss) … and the list goes on. And in due course, the grimy harshness of “Her Smell” (running over two hours) does start to reek ever so slightly—the accumulation of the intense psychosis on display feels like a stylistic showcase instead of the uncompromisingly human character study I am assuming Perry intended to make.

Much of this miscalculation is due to Perry’s insistence on keeping Becky and her art at a curious distance, save for a couple of songs she gets to perform. Even when the filmmaker’s repeat cinematographer Sean Price Williams loyally twirls around Moss’ unsteady and restless body and at times, stays invasively close to her magnificent canvas of a face smeared with tears, wrinkles and smudgy make-up, Becky feels just a touch out of reach. While each of the film’s sections starts with home-style videos serving as brief Preludes into the world of the “former” (normal?) Becky, Perry quickly pulls us back into frenzied episodes, with Keegan DeWitt’s ominous score pumping through the veins of “Her Smell” in uniform but atonal beats. One memorable section sees Becky at her most despicable, when she treats both her band and Akergirls (Cara Delevingne, Ashley Benson and Dylan Gelula), a newish collaborating band that clearly worships her, abhorrently at a recording studio. Others follow her through hallways and backstage rooms as she lands from target to target to unleash her energetic anger. But none of that quite puts us inside of her mind.

And yet, despite all the claustrophobic airlessness of “Her Smell,” you won’t be able to quit it if you stay with its jumbled dialogues and dizzying pace long enough. And this is entirely thanks to Moss, who, in her third collaboration with Perry, sinks her claws into the film with peerless dedication and turns it into something halfway rewarding. To know Moss is to recognize her unique ability to crack open any character by slicing it into two—she did this with “Mad Men”’s Peggy Olson, the innocent and successful copywriter who harbored a deep secret all throughout the series. She icily did this as the oppressed Offred in “The Handmaid’s Tale.” And she quiet plainly portrayed menacing doubles in both “The One I Love” and most recently, Jordan Peele’s “Us.”

With “Her Smell,” Perry gives Moss a boundless playground to stretch those twin muscles to unnerving effect, eventually allowing her character both a quiet segment of reconciliation (the film’s strongest part) and a comeback concert of sorts in the finale (a hazy afterthought). If Becky’s journey doesn’t quite form a credible arc, you can’t really blame it on Moss. She runs away wild and free with admittedly exhilarating material, even though Perry concerns himself more with how Becky is perceived from the outside by those who project their expectations onto her, than how she feels and grows on the inside. While this feels like cheat for a film refreshingly centered on an unlikable female antihero—a desperately needed breed of character in cinema—you somehow excuse it, as Moss boldly makes the stench of “Her Smell” her own.